Macias, a former journalist with NBC and CBS, owns the public relations agency Macias PR.

The Fulcrum presents We the People, a series elevating the voices and visibility of the persons most affected by the decisions of elected officials. In this installment, we explore the motivations of over 36 million eligible Latino voters as they prepare to make their voices heard in November.

According to the Census Bureau, the Hispanic, Latino population makes up the largest racial or ethnic minority group in America. But this group is not a monolith. Macias explores providing a more accurate and nuanced understanding of this diverse population.

Several new political polls examine how Hispanic voters view former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris. Not surprisingly, the polls are all over the place, even though they were taken around the same time.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll shows Hispanics prefer Trump over Harris when it comes to immigration, while a UnidosUS poll shows Hispanics overall prefer Harris rather than Trump. Narrowing down the Hispanic voter gets even more complicated when you include language spoken at home. Is it a Spanish-speaking household, bilingual or primarily English? NBC News covered that angle, showing a 16 percent swing between Spanish- and English-speaking households.

Rafael Mendez, 41, falls under every one of those categories. He is Mexican-American, born in Phoenix, and married to a woman from Sonora, Mexico. He speaks Spanish at home and English at work, where he works with Cubans and Venezuelans. He said all three cultures couldn’t be more different.

“The way they speak and carry themselves, even our Spanish is different,” Mendez said. “The Cubans, they like to keep to themselves and speak to themselves from what I see. The Venezuelans, they love their country. They have their flags everywhere. You can’t tell them nothing wrong about Venezuela because they get offended. And the food is different. [Mexican] food is spicy. The others [Cuban and Venezuelan foods] don’t have our spices. I love my hot sauce.”

Jack Spradlin is not Latino, but on the inside, he might as well be Mexican.

“I grew up in San Diego and was raised by a Mexican lady. She was a live-in nanny and taught me Spanish,” Spradlin said. “I thought for sure I would marry a Mexican woman.”

But he ended up marrying a woman from Venezuela. They met while he was playing professional baseball in Venezuela, giving him a unique perspective on Mexican and Venezuelan cultures.

“It’s a culture shock compared to Mexico. It’s night and day,” he said, referring to the Venezuelan and Mexican cultures. “The accents are different, the vocabulary and words they use are different. The food is different. [Venezuela] is more of a Carribean-type place.”

These different cultures are partially why the majority of the media and pollsters can’t figure out the Latino voter. Hispanics are essentially smaller clusters of cultures — brought together by commonalities, food, family and plight.

Cuba has been under communist rule for decades, where dissidents are persecuted and killed, while Venezuelans have lived under dictators for decades. The government woes in both countries have led to poverty, high crime and brain drain. That common plight from back home also connects these families together.

The Hispanic vote in november

In 2016, I wrote an article for CNBC that contradicted what many political pundits were saying about Hispanic voters. At the time, Sen. Ted Cruz (Texas) and Marco Rubio (Fla.) were creating a splash with the Republican establishment after they announced they were running for president. Many political pundits predicted the Cuban senators would bring more Hispanics under the GOP umbrella.

I predicted they were going to get it wrong. Latinos experience different plights based on these past experiences. Both Cruz and Rubio are Cuban-American, which is a completely different culture from the Mexican and Venezuelan cultures. It’s nuanced, but if you’re in the middle of these cultures, you will likely have experienced it.

This is one reason I think Cruz will have difficulty beating his Democratic challenger in Texas this November. Cruz is Cuban-American in a state dominated by Mexicans. Roughly 9.6 million people in Texas identify as being of Mexican descent — compared to roughly 130,000 Cuban-Americans in the Lone Star.

On the other spectrum, Rubio’s seat is safe with the large Cuban vote across Florida. The state has the highest concentration of Cuban-Americans with roughly 2 million living in Florida.

The different shades of U.S. immigration policy

When it comes to immigration policy, Hispanics are also treated differently based on their country of origin.

For example, Cuban refugees who reach American soil can stay and apply for a green card after a year. It’s known informally as the “ wet foot, dry foot ” policy, where Cuban migrants who are intercepted at sea are returned to Cuba or a third country, while those who make it to the U.S. soil can stay. The Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 allows Cuban immigrants or citizens in the United States to apply for a green card after a year of arrival.

Immigration policy for Venezuelans was updated in September 2023, allowing them temporary protected status in the United States for 18 months. Immigrants from Mexico don’t have any of those protections.

Despite the different cultures between Latin countries, Mendez understands the various needs for U.S. immigration policies.

“It makes sense,” Mendez said. “You can’t live in Cuba and Venezuela. You criticize the government, you get killed. The government kills them. Mexico is different. It’s a rich country with a lot of money.”

In the weeks leading to Election Day, The Fulcrum will continue to publish stories from across the country featuring the people who make up the powerful Latino electorate to better understand the hopes and concerns of an often misunderstood, diverse community.

What do you think about this article? We’d like to hear from you. Please send your questions, comments, and ideas to newsroom@fulcrum.us.

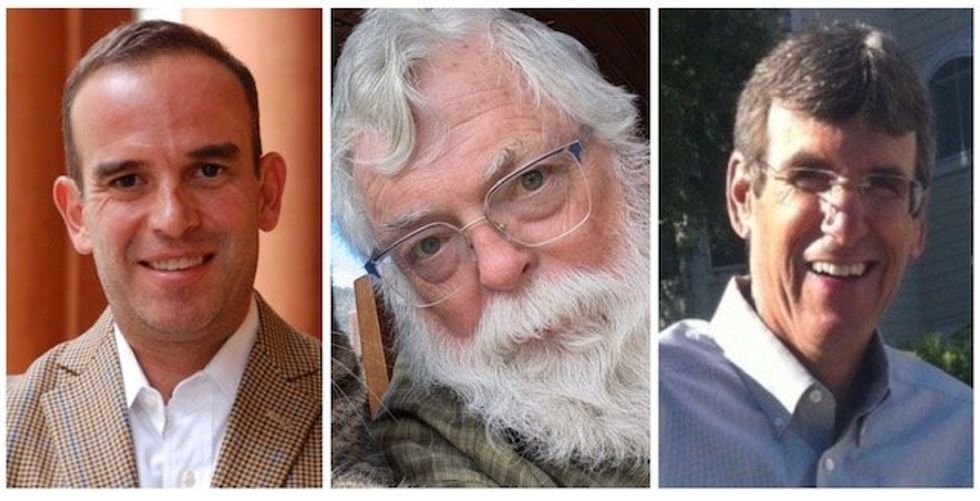

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne