Lamendola is director of research at RepresentWomen. Follow her on X @Lamendola_. Scaglia is the research manager at RepresentWomen.

This week, RepresentWomen published our 11th annual Gender Parity Index, a comprehensive measure of women’s representation at the national, state, and local levels of government. Our findings show progress toward gender balance is slow and possibly even stagnating.

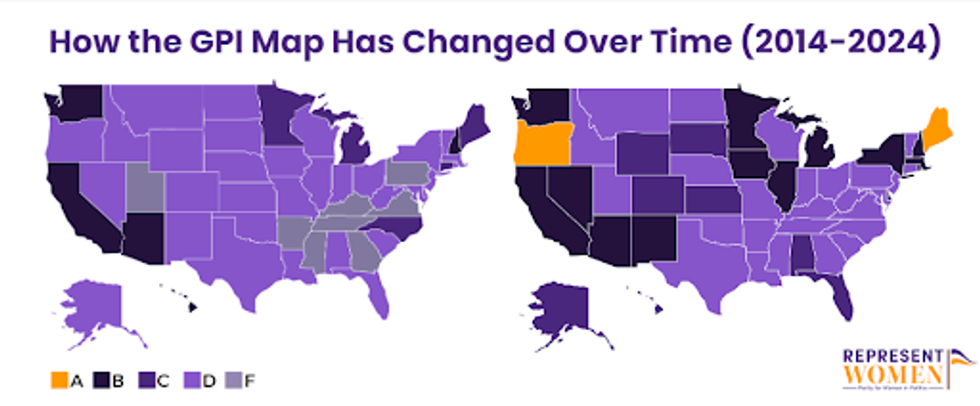

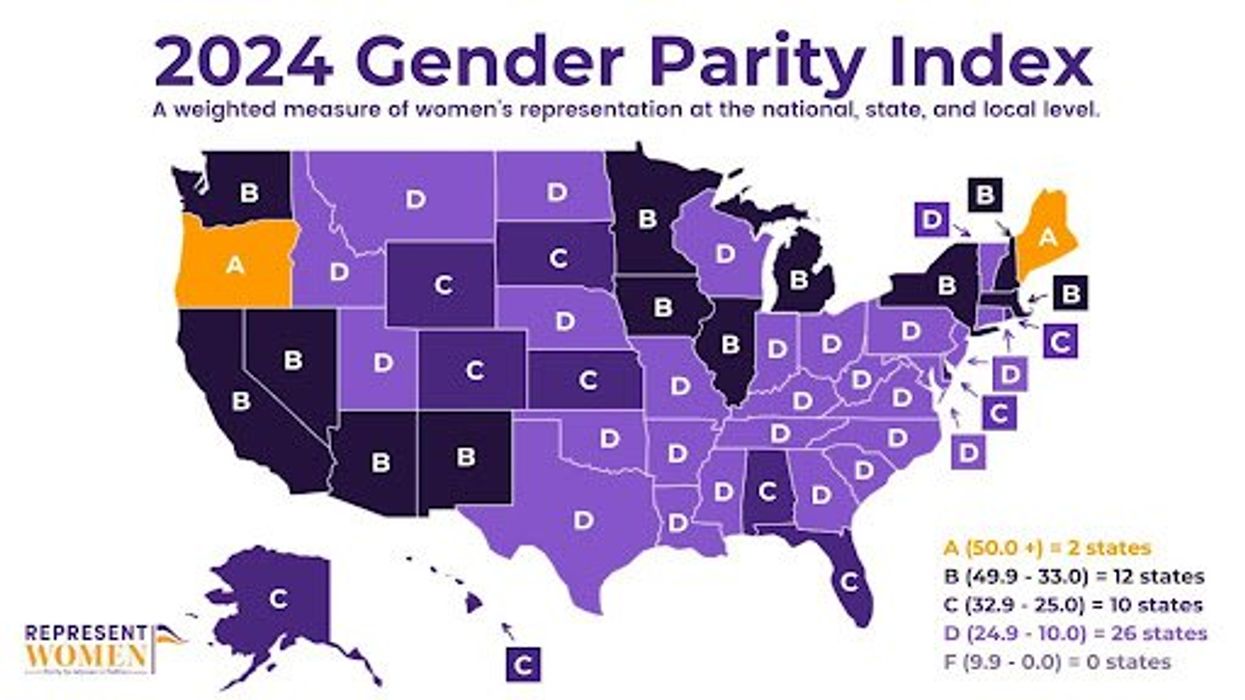

The Gender Parity Index, launched in 2013, awards each of the 50 states a score (0-100), letter grade (A-F), and ranking (1-50) based on that state’s proximity to parity. A perfect score is 50/100. Eleven years ago, 40 states earned “D” grades (<25.0 points) or “F” grades (<10.0 points), and the remaining 10 states were split evenly between “C” grades (<33.0) and “B” grades (<50.0). No state earned an “A” until New Hampshire got one in 2015-2018, and then again in 2020. This year, Oregon and Maine received “A” grades for the second time, but the case of New Hampshire shows the importance of tracking representation over time.

Despite Oregon and Maine’s success, the majority of states earned “D” grades, and the remaining 22 states earned “B” and “C” grades. For the first time ever, no state received a failing grade. Louisiana, the only state to receive an “F” for eight years straight (2016-2023), made major gains, electing its first woman attorney general, Liz Murril, and second woman secretary of state, Nancy Landry.

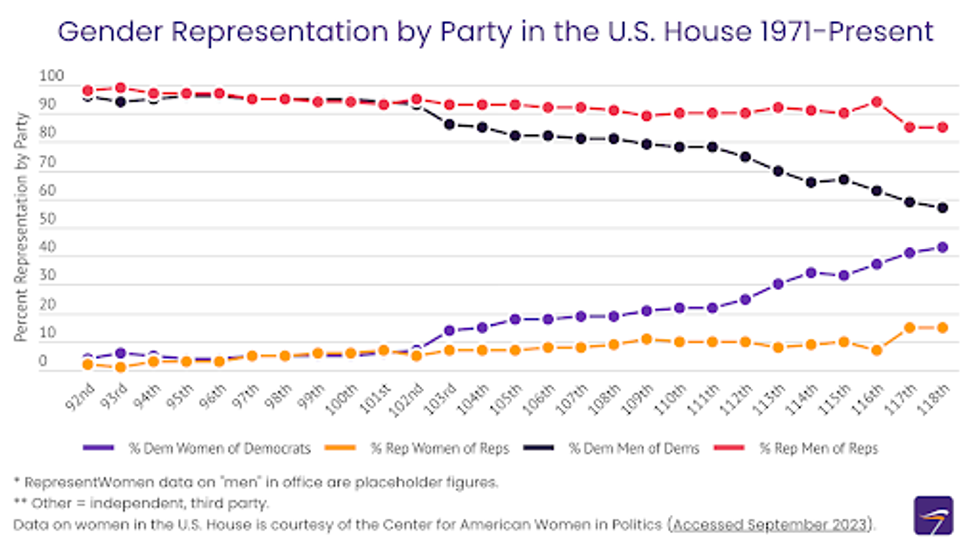

Earlier this year, RepresentWomen analyzed the composition of the U.S. House of Representatives ( Party Composition by Gender 2013-2024). We found that although less than 30 percent of all House members are women, almost half (43 percent) of Democratic Representatives are women, while 28 percent of Republican Representatives are women. Unless (a) more Democratic women are elected than men, or (b) more Republican women are elected — which we know is unlikely this cycle — progress to parity will likely slow.

Additional research from the Center for American Women in Progress supports this: The number of major-party women candidates in 2024 has fallen by 20 percent for the U.S. House and 26 percent for the U.S. Senate. This decline is seen in both major parties, emphasizing that without intentional action, progress is not self-sustaining.

Rhetoric touting record-breaking wins for women’s representation often overshadows the reality of stagnation in the number of women running for office at the national, state and local levels. Women remain underrepresented at every level of government in the U.S., comprising over 50 percent of the population but holding just under one-third of all elected positions. Incremental score changes by one or two points do not necessarily reflect broad, system-wide movements to elect women to all levels of government.

The 2024 index reflects our complex political landscape, suggesting progress in women’s political representation may stagnate or even backslide. This index shows the most movement for women at the state and local levels: Louisiana elected two new woman as state executives, and Indiana elected nine new women to local offices. To make lasting progress in women’s representation, we must take a systems-level approach that creates opportunities for women to enter the political sphere and supports the women already in office. This year’s index finds:

- The U.S. remains over halfway to parity, with an average Parity Score of 27. However, in contrast to 2023, fewer states have passed the halfway mark: Only 24 of the 50 states earned above 25 points.

- For the first time in the index's history, no state earns an “F” grade. After eight consecutive years of scoring under 10 points, Louisiana earned its first “D” grade and moved up to 45th place. This shows just how consequential a single election cycle can be, especially with open seats.

- To sustain progress, we need solutions that support women in office. The decline in incumbent women running for Congress this cycle suggests that progress will likely plateau or regress if we do not ensure a modern and safe work environment.

- Progress must occur across levels of government. Vermont's case shows that gains at one level can be counterbalanced by losses at another, ultimately decreasing the overall score.

Our research specifies the barriers women face when running, winning and serving. These include funding and support disparities from political parties and other major donors, media bias, unfair voting systems, imbalanced caregiving responsibilities, and lack of mentorship networks. However, our research also shows that actionable solutions exist and have shown success. Systems change — such as supporting women within the party establishment, implementing ranked-choice voting and instating fair legislative practices — are all viable methods for getting women to run, win and serve effectively in political office.

The 2024 presidential race demonstrates such change, with Kamala Harris well-positioned to win the Democratic party nomination and become the first Black woman and first Asian American person to do so. Harris’ candidacy would undoubtedly advance the conversation of women’s viability to hold political leadership positions, including in the down-ballot races that will shape changes in the 2025 Gender Parity Index.

Achieving gender-balanced governance is not a one-time goal. Sustaining women’s representation requires enacting changes that equalize the playing field for women in the long term. We need to view our lack of political gender balance with a sense of urgency if we are to build a system that achieves gender balance within our lifetimes.

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?