Patterson is an assistant professor of secondary school studies at West Virginia University.

I'll never forget a student's response when I asked during a middle school social studies class what they knew about black history: "Martin Luther King freed the slaves."

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in 1929, more than six decades after the time of enslavement. To me, this comment underscored how closely Americans associate black history with slavery.

While shocked, I knew this mistaken belief reflected the lack of time, depth and breadth schools devote to black history. Most students get limited information and context about what African Americans have experienced since our ancestors arrived here four centuries ago. Without independent study, most adults aren't up to speed either.

For instance, what do you know about Reconstruction?

Based on my experience teaching social studies and my current work preparing social studies educators, I consider understanding what happened during the Reconstruction essential for exploring black power, resilience and excellence.

During that complex period after the Civil War, African Americans gained political power yet faced the backlash of white supremacy and racial violence. I share the concerns many writers, historians and other scholars are raising about the shortcomings of what schoolchildren traditionally learn.

As most students do learn, the United States gained three constitutional amendments that extended civil and political rights to newly freed African Americans following the Civil War.

The 13th, ratified in 1865, banned slavery and involuntary servitude except for the punishment of a crime.

The 14th, ratified three years later, granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to all people born in the United States, as well as naturalized citizens – including all previously enslaved individuals.

Then, the 15th Amendment asserted that neither the federal government nor state governments could deny voting rights to any male citizen. Feb. 3 marks the 150th anniversary of its ratification. The anniversary is a good opportunity to learn about how the amendment was supposed to guarantee that the right to vote could not be denied based on "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

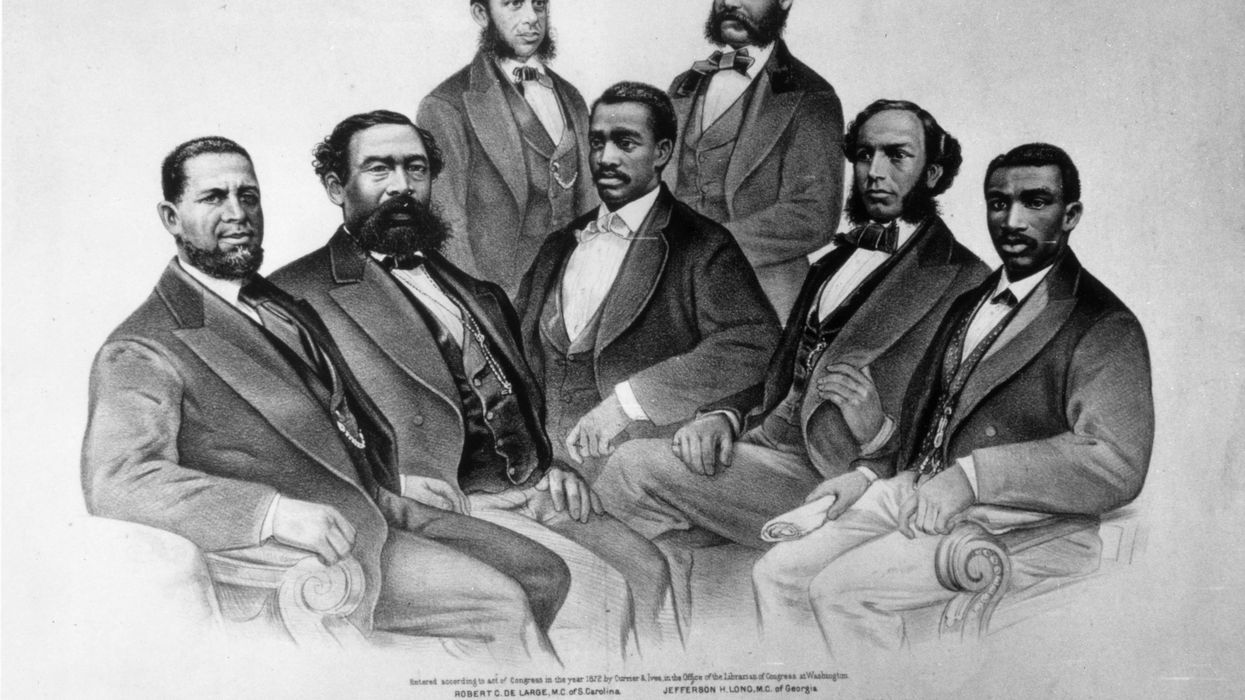

Few history and social studies classes explore how these changes made it possible for African American men to use their newfound political power to gain representation.

Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American senator, represented Mississippi in 1870 after the state's Senate elected him. He was among the 16 black men from seven southern states who served in Congress during Reconstruction.

Revels and his colleagues were only part of the story. All told, about 2,000 African Americans held public office at some level of government during Reconstruction.

White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan also formed. These terrorist groups engaged in violence and other racist tactics to intimidate African Americans, voters and legislators. They thus made the accomplishments of black politicians even more impressive as they served as public officials under the constant threat of racial violence.

While African American women gained the right to vote in 1920, when the 19th Amendment passed. However, this right was limited in many states due to discriminatory laws.

Many were activists and women's suffrage movement leaders. Through public speaking, prolific writing and developing organizations dedicated to racial and and gender equality, they fought for equal rights and dignity for all.

Among the black women who were activists during Reconstruction were the five Rollins sisters of South Carolina, who fought for female voting rights; Maria Stewart, an outspoken abolitionist before the Civil War and suffragist once it ended; Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the first black woman in North America to edit and publish a newspaper; Ida B. Wells, a journalist who raised awareness of lynching, and Mary Church Terrell, founder of the National Association of Colored Women.

Before the Civil War, many states made teaching enslaved individuals to read a crime. Education quickly became a top priority for black Americans once slavery ended.

While northern, largely white philanthropists and missionary groups and the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (better known as the Freedmen's Bureau) did help create new educational opportunities, the African American public schools were largely built and staffed by the black community.

Many new institutions of higher education, now called Historically Black Colleges and Universities or HBCUs, began to operate during Reconstruction.

These schools trained black people to become teachers and ministers, doctors and nurses. They also prepared African Americans for careers in industrial and agricultural fields. And t hese colleges and universities train a disproportionate share of black doctors and other professionals even today.

Storytelling, multimedia experiences and trips to historic sites and creative museums help get people of any age interested in learning about history.

The National Constitution Center in Philadelphia has a new permanent exhibit on the Civil War and Reconstruction.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture contains artifacts from the Reconstruction era. It's also making the records of the Freedmen's Bureau, including the names of formerly enslaved individuals following the Civil War, available online.

Another option is the Reconstruction Era National Historic Park in Beaufort County, S.C.

I also recommend watching the PBS documentaries about Reconstruction by the scholar and filmmaker Henry Louis Gates Jr. and reading the young adult book he wrote about the era with children's nonfiction writer Tonya Bolden.

Also, Teaching for Change curates a booklist on Reconstruction for middle and high school students. And the Zinn Education Project Teach Reconstruction Campaign offers a variety of resources including readings, primary sources and even lesson plans.

Inside Look | Reconstruction: America After the Civil War | PBSyoutu.be

As W.E.B. DuBois observed, racist laws and violent tactics in many states actively limited black freedom.

"The slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery," he explained.

With the latest voter suppression efforts restricting access to the ballot box for voters of color and the resurgence of racist violence and vitriol today, DuBois' words sound eerily familiar. At the same time it's reassuring to recall how quickly formerly enslaved African Americans made their way to schoolhouses and public offices.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Click here to read the original article.

![]()