Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

As Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has continued to slam early voting and voting by mail at his rallies, a neighbor — a retired math teacher — asked me how we know that only registered voters are voting and people aren’t voting more than once.

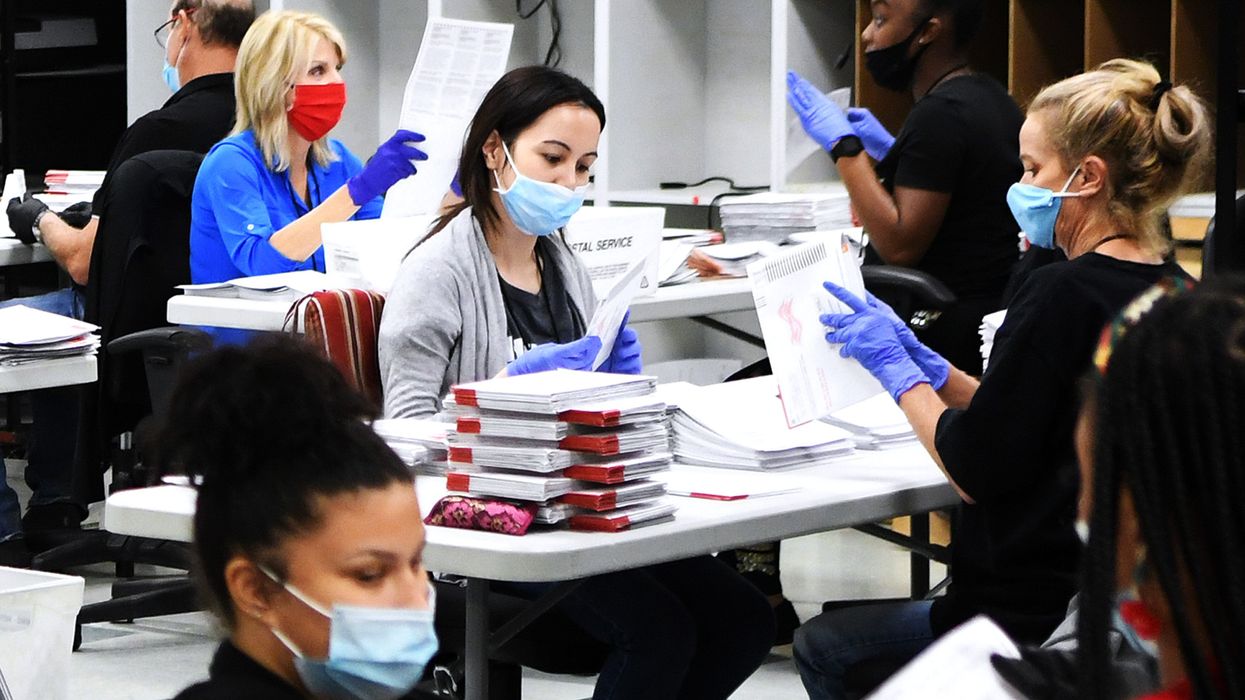

It was barely after 7 a.m. and I was heading to a seasonal job at my county election headquarters. There, I was part of a team that was processing returned mail ballots and alternatively in a call center answering voters’ questions and concerns.

In both of those settings I was privy to the behind-the-scenes machinery, computer systems, information and procedures that track individual voters and their ballots. The data and systems that I saw and used could be in any suburban county in America.

I’m in California, where voters can register online, submit paper applications or do so while visiting government agencies — such as the motor vehicle department. California mails every voter a hand-marked paper ballot (most states require a voter to apply for one) and, like most states, still has early and Election Day in-person vote centers and polling places.

Legal Voters

Trump and many Republicans have claimed that voter rolls are filled with ineligible voters and said Democrats use these bloated lists to fabricate voters and cast reams of illegal votes. Let me tell you why those assertions are almost entirely false.

The partisans making these charges probably don’t know how much information election officials have about every voter, how and when they vote, their voting histories. Similarly, they probably don't know how much data is generated and used to track every ballot — while protecting the secrecy of the voter’s choices on those ballots.

Impersonating voters is not as easy as some partisans would have you believe. When people register, they typically fill out an application with their name, residential address, mailing address, email, phone number, date and place of birth, driver’s license or state ID card number, Social Security number, language and political party preference. They also attest to being an American citizen and sign the form under penalty of perjury.

This information is just the starting line of the data that election officials use and generate to verify and track legal voters. The registration database also notes if a person temporarily lives overseas. They generate internal ID numbers for voters and compile histories of when, where and how people voted in each election (by mail, in-person, etc.). They also collect and compile signatures from each time people vote or update their registration information (if they move, marry and change names, etc.).

When election officials answer the phones, the first thing they do is look up a voter’s registration information and status. They can see if everything is up to date or if something is missing. They can see where that person’s ballot is in the process. But election workers cannot change or alter any of that information. Only voters can do that.

Simply stated, impersonating another voter or fabricating registrations is not easily done. That’s why so-called voter fraud is extremely rare. Those who make rare efforts to do so almost always get caught, because officials have many ways to spot if something is awry.

Legal Ballots

Just as registration data is complicated, so too is the information trail that surrounds ballots. Here, it is important to distinguish between ballots — which come in envelopes in the mail or inside folders at voting sites – from the votes on those ballots.

Election officials have many protocols to ensure that only registered voters get a ballot and that ballots, especially those that are mailed out and returned, are vetted. They anticipate setting aside some messily marked return envelopes for closer looks before they can be opened, and the ballot is removed and put in batches to be counted.

This process starts with signatures. At polling places and on ballot return envelopes, voters must sign in or sign their return envelope. Those signatures are scanned and go into each voter’s electronic file. With mail ballots, officials then sit before computers and compare the latest signature to what’s in the voter’s file. There are guidelines and if something does not appear right, the ballot is set aside for further review.

A typical election operation has machines that sort and sift hundreds of mail ballot envelopes at a time — and repeatedly do this as signatures are vetted. Just as the voter registration system has lots of hidden identifiers in its data, the ballot inventory system has its own identifiers. Return envelopes have barcodes and QR codes that identify the voter, their precinct the ballot number and more — all apart from the signature.

The system also tracks when ballots are sent out, when they are returned, if they have been reported lost, if they are resent,and any problem that might arise. Election officials sitting at computers in county headquarters see all of this.

Their system records and reports every imaginable problem. A voter’s or ballot’s status may be pending (usually meaning address information is missing something). A return envelope signature may be missing. A voter may be recently deceased.

The records have other details. The system notes how a ballot was returned. It could be at the election office, at a drop box, at an early voting center, by mail or fax (for overseas voters) or at an Election Day polling site. It notes if a person tried to vote twice and prevents a person from voting more than once. (Often, a voter will mail their absentee ballot but get antsy and go to a polling place to vote. In this case, the system tracks which ballot was received and which was canceled.)

These are just some of the details and data that officials see and routinely work with. Like many things in life, there’s more going on than meets the eye. Because voting and voting information is private, much of what I’m describing is not exposed to the public.

Observers, of course, can watch what election officials are doing. In most cases, election workers are parsing the range of information I described to ensure that every legal voter gets a ballot in their hand and returns so it will be counted. And when a problem arises, it can be traced, found, fixed and annotated — every step of the way.

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne