One of the first executive orders signed by President Trump on the evening of his inauguration was to immediately withdraw the U.S. from the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations agency tasked with coordinating a wide range of health activities around the world. This did not come as a surprise. President Trump tried to pull this off in 2020 amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Upset at how WHO handled the pandemic, President Trump accused it of succumbing to the political influence of its member states, more specifically to China. However, the structure of the WHO, which is made up of 197 member states, prevents it from enforcing compliance or taking any decisive action without broad consensus. Despite its flaws, the WHO is the backbone of global health coordination. When President Joe Biden came into office, he reversed the decision and re-engaged the US with the WHO.

WHO’s mission is to promote health, keep the world safe, and serve the most vulnerable. Besides taking the lead in coordinating the world’s response to health emergencies, WHO works with member states and partners to eradicate polio, deliver essential health services, set international guidelines for medicine and vaccines, and promote universal health coverage. Its mandate is broad and ambitious.

Like all large bureaucratic institutions, the WHO could benefit from reform and improved management practices. But to unilaterally pull out of the largest coordinating body on everything global health, is like throwing the baby out with the water. It is a draconian move that undermines everyone’s health in a globalized world where people, goods, and services move around and can become vehicles for diseases.

Stephanie Psaki, a former U.S. coordinator for global health security at the National Security Council, said in a January 28 op-ed on STAT that WHO withdrawal “will sever ties with critical partners, cut our resources to stop outbreaks before they reach our shores, diminish our access to vital early warning data, slash the pipeline of innovative vaccines and treatments that could be used in an emergency, and hamper the ability of federal agencies to act quickly to warn Americans about emerging threats.”

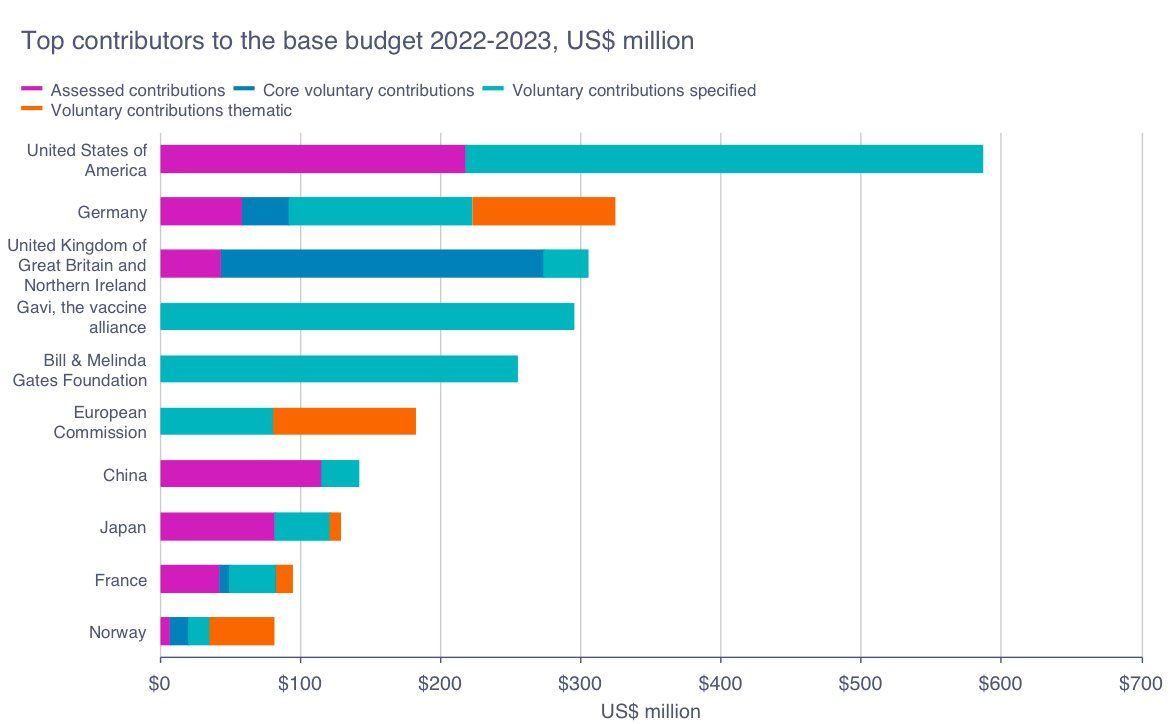

“Unfairly onerous payments from the United States” are cited in President Trump’s executive order to withdraw from WHO. Though the U.S. is the single biggest donor to this UN agency, giving $1.284 billion in the 2022 and 2023 fiscal years, it is critical to understand that mandatory contributions are assessed on a country’s domestic product and population size and only represent 20% of WHO’s total budget.

The rest of WHO’s budget comes from voluntary contributions earmarked for specific health programs. In fact, mandatory contributions from the US to the WHO are not much higher than those from China, which are $218 million versus $115 million. Funds for the WHO represent 4% of America’s budget for global health. For a detailed breakdown of the U.S. global health budget, consult this resource.

Reforming WHO is a process that is already in progress, said Elisha Dunn-Georgiou, President and CEO of the Global Health Council, in an email to the Fulcrum. “In recent years, under the direction of the U.S. and other member states, the WHO has made several changes to improve financial management and operational performance,” she explains. Withdrawing from the WHO also means having less influence in creating a more efficient agency. This resource from the BetterWorld Campaign, shared by Dunn-Georgiou, provides some insight into WHO reforms, which include how member fees are calculated.

Katelyn Jetelina, an adjunct professor at the Yale School of Public Health and the publisher of Your Local Epidemiologist, a newsletter on Substack, says that self-interest is one reason all Americans should care about the WHO withdrawal executive order. “Infectious diseases don’t respect borders. Covid-19, flu, Ebola—you name it. Even if the U.S. is well-equipped to handle its own health challenges, our safety depends on the rest of the world being equipped, too.”

This executive order comes at a time when the country is facing one of the largest recorded tuberculosis outbreaks in U.S. history in the state of Kansas and an Avian influenza outbreak in poultry and dairy farms that has already caused one human death. To make matters worse, a gag order was imposed on the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to stop communicating with the WHO immediately. This hinders data exchange on current disease outbreaks to protect all Americans.

Another reason Americans should care about WHO withdrawal, Jetelina says, includes geopolitical implications and the likelihood that others, especially China, will step in to fill the public health leadership vacuum left by the United States.

Technically, countries cannot withdraw from the WHO without giving a year’s official notice. However, a story published in KFF Health News reports that in his order, President Trump cites the termination notice he gave to WHO back in 2020. If Congress or health experts push back, his administration can argue that more than a year has passed. This is a calculated move rooted in Project 2025 priorities.

A week after the WHO executive order, a State Department memo issued a 90-day Stop Work Order on all U.S. foreign assistance—less than 1% of the federal budget. For comparison, defense spending accounted for 13.3% in 2023. Halting these life-saving health programs in the world's poorest nations will have devastating consequences.

Former USAID global health administrator Atul Gawande warned on X that the order disrupts critical programs, including HIV drug distribution for 20 million people, polio eradication, and containment of deadly outbreaks like Marburg in Tanzania and an mpox variant killing children in West Africa. "Make no mistake—these essential, lifesaving activities are being halted right now," he stressed. "Consequences aren’t in some distant future. They are immediate."

Atul Gawande's social media post

Atul Gawande's social media post

Being part of the WHO is a strategic U.S. investment, a “soft diplomacy” tool, health experts say. “The investments the U.S. government makes in global health results in enormous returns, providing both economic and national security rewards as well as improving our standing throughout the world,” said Dunn-Georgiou. “They result in job creation in, among other sectors, biotechnology, medical devices, and pharmaceuticals. It also bolsters local economies through new contracts.”

On Tuesday, January 28, a State Department memo signed by Marco Rubio temporarily lifted the Stop Work Order for select life-saving activities overseas, including core life-saving medicines, medical services, food, and shelter. However, withdrawal from the WHO remains in place and blocks data exchange and disease surveillance with this global institution, potentially resulting in dire consequences for Americans.

Beatrice Spadacini is a freelance journalist for the Fulcrum. Spadacini writes about social justice and public health.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room