Michelle Obama famously advised Democrats, "When they go low, we go high." This is advice that Democrats no longer can afford to heed if they have any hope of helping to save American democracy.

That fact is evident if they are going to resist President Trump’s plan to get red states like Texas, Missouri, and Florida to redraw their congressional districts in advance of the 2026 midterm elections. As the AP reports, “At Trump’s urging, Texas Republicans are looking to redraw congressional maps to favor GOP candidates during a 30-day special legislative session…. Trump has said he wants to carve out five new winnable GOP seats.”

Nothing subtle about that.

Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, noting that redistricting would have to be done by the Missouri legislature and governor, was almost as overt as the president in explaining the rationale for redistricting. As he put it, “I’d love to have more Republicans.”

One day after the Missouri House Speaker Pro Tem, Chad Perkins, seemed to throw cold water on that idea, he got a call from the White House telling him that it was important to the president that Missouri act now to target the two congressional seats in that state that Democrats now hold. Perkins was informed that every Republican in the state legislature, as well as Missouri’s Republican governor, Mike Kehoe, would be receiving a similar call.

After the call, Perkins candidly acknowledged that “The biggest impetus to move on redistricting would be a desire to please the president. ‘If you’re a Republican state senator, or a Republican state representative, you don’t want to be on the wrong side of this president.’”

On July 28, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis said he, too, was looking into the possibility of redrawing districts. Currently, Republicans hold twenty of the state’s twenty-eight seats in the House of Representatives.

These comments suggest that officials in blue states should fight fire with fire by making their own efforts to redraw districts, increasing the chances for Democrats to take back the House next year. They have little time to waste.

Now is not the time for them to be squeamish.

As in many other areas, the president and his allies can thank the United States Supreme Court for opening the door for Trump’s kind of partisan shenanigans. Five years ago, the Court had a chance to stop political gerrymandering in its tracks.

But it refused to do so.

Writing for a five-Justice conservative majority, Chief Justice Roberts took us on a cook’s tour of the history of using gerrymandering to advance one or another party’s interests. “Partisan gerrymandering,” Roberts explained, “was known in the Colonies before Independence, and the Framers were familiar with it at the time of the drafting and ratification of the Constitution.”

“Aware of electoral districting problems,” the Chief Justice continued, “the Framers chose a characteristic approach, assigning the issue to the state legislatures, expressly checked and balanced by the Federal Congress, with no suggestion that the federal courts had a role to play.” Roberts argued that if the courts intervened to stop legislators from monkeying around “when drawing district lines… (they) would essentially countermand the Framers’ decision to entrust districting to political entities.”

He concluded that “Partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.”

The Court’s four liberal Justices saw things very differently. Justice Elena Kagan sounded the alarm.

As she noted, “The partisan gerrymanders in these cases deprived citizens of the most fundamental of their constitutional rights: the rights to participate equally in the political process, to join with others to advance political beliefs, and to choose their political representatives. In so doing, the partisan gerrymanders here debased and dishonored our democracy, turning upside-down the core American idea that all governmental power derives from the people.”

“These gerrymanders,” she observed, “enabled politicians to entrench themselves in office as against voters’ preferences.”

What is happening now in Texas and soon in Missouri and Florida shows how right Justice Kagan’s warning was.

Recall that legislative redistricting typically happens every ten years when states need to adjust things in light of the latest census data. Since the next census won’t happen until 2030, tradition suggests that the process of adjusting congressional districts in light of population changes would not have started until 2031.

Mid-decade redistricting is, as Florida’s Democratic Party Chair Nikki Fried notes, “nothing more than a desperate attempt to rig the system and silence voters before the 2026 election.”

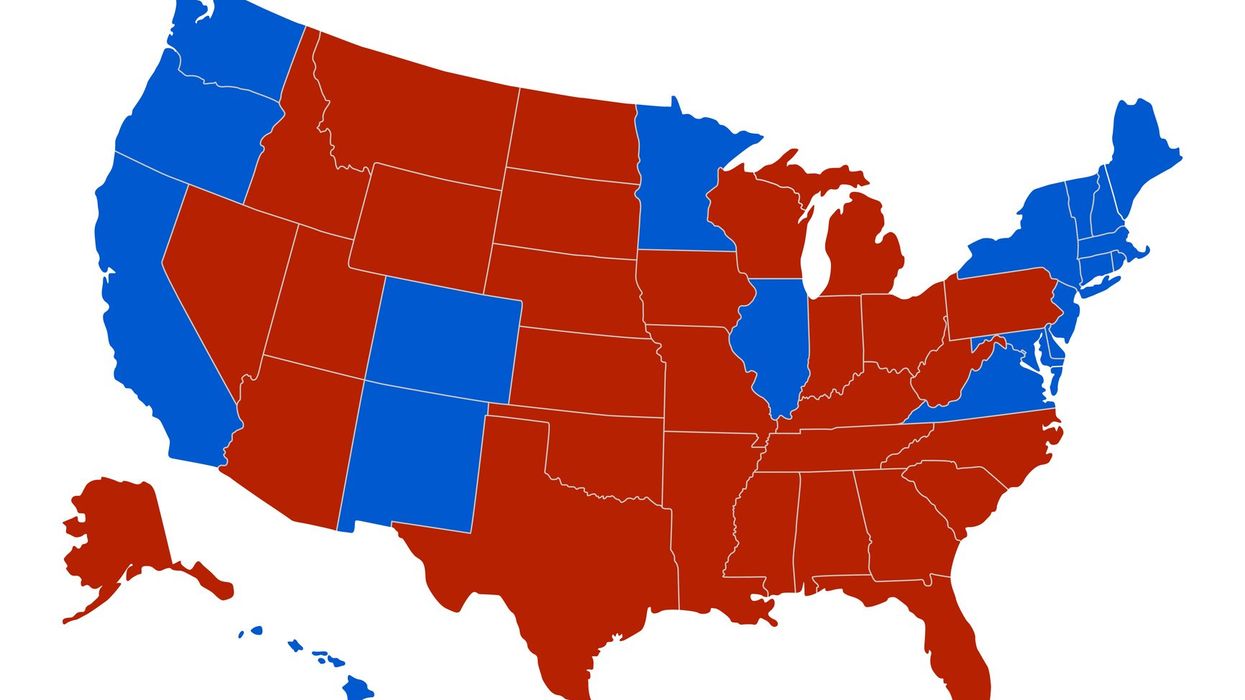

Democrats in Texas, Missouri, and Florida do not have the power to prevent that from happening. That is why they need to use the power they have in states like California and New York to meet Republican efforts in red states, gerrymander for gerrymander.

Sorry, Michelle Obama.

As New York Governor Kathy Hochul put it, "’What I'm going to say is, all is fair in love and war….. If there's other states that are violating the rules that are going to try and give themselves an advantage, all I'll say is I'm going to look at it closely….’"

Look closely? That’s hardly the kind of rallying cry that Democrats need to mount an effective response to Trump’s plan to stack the deck for 2026.

Governor Newsom seems more eager to lead the charge. However, he would be hamstrung by the fact that in 2010, voters in his state voted to take the politics out of redistricting by having it done by an independent citizens’ commission. KQED quotes Professor Sara Sadhwani, a member of that commission, who explained that in drawing congressional districts after the 2020 census, “’We never looked at voter registration data at all” after the 2020 census.

“Communities,” she said, “would define themselves: in some cases, it would be because of some geographic point — whether that was a freeway corridor or a mountain range or oceans — sometimes it was historic racialized communities, in some instances it was business communities.” That approach produced many more competitive congressional races in the Golden State than would otherwise have been the case.

Seems like a democratic way of doing things.

But that was then.

Now Newsom sees things in a different light. “Everything is at stake,” he says, “if we’re not successful next year in taking back the House of Representatives…. If we don’t put a stake into the heart of this administration, there may not be another election in 2028.”

As the great political theorist Michael Walzer explained more than fifty years ago, “No one succeeds in politics without getting his hands dirty.” That is truer in Trump’s America than it has ever been.

Sorry, Michelle Obama.

Austin Sarat is the William Nelson Cromwell professor of jurisprudence and political science at Amherst College.

Mayor Ravi Bhalla. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken

Mayor Ravi Bhalla. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken Washington Street rain garden. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken

Washington Street rain garden. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken