Eisner is a Ph.D. student in history at Johns Hopkins University. Froomkin is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center.

Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election not only failed, but some of them also rested on a misreading of the U.S. Constitution, as our new analysis argues. The relevant constitutional provision dates back to just after the Civil War, and contemporaries recognized it as a key protection of American democracy.

In November 2020, as it became clear that Trump had lost the popular vote and would lose the Electoral College, Trump and his supporters mounted a pressure campaign to convince legislatures in several states whose citizens voted for Joe Biden to appoint electors who would support Trump’s reelection in the Electoral College votes.

Trump and his allies contacted Republican lawmakers in Michigan, Georgia and Pennsylvania to induce the state legislatures to overturn the results of the popular election. Ginni Thomas, the wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, emailed GOP legislators in Arizona, encouraging them to “ensure that a clean slate of Electors is chosen.”

These efforts were relying on a provision of the Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, that states, “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors.” Trump and his supporters wanted state lawmakers to discard their citizens’ votes and simply appoint electors who would back Trump’s reelection bid.

As part of their efforts, Trump and his supporters claimed that the Constitution allowed state legislatures to directly choose a slate of electors without a popular vote.

But they were wrong. There was a safeguard already in place – and it remains today, defending against this approach being used to subvert the 2024 presidential election.

An effort to protect voters’ power

In almost every state, the candidate who gets the most popular votes for the presidency receives all of that state’s electoral votes. Nebraska and Maine have slight exceptions – but those states’ laws still deliver the majority of their electoral votes to the person who wins the popular statewide vote.

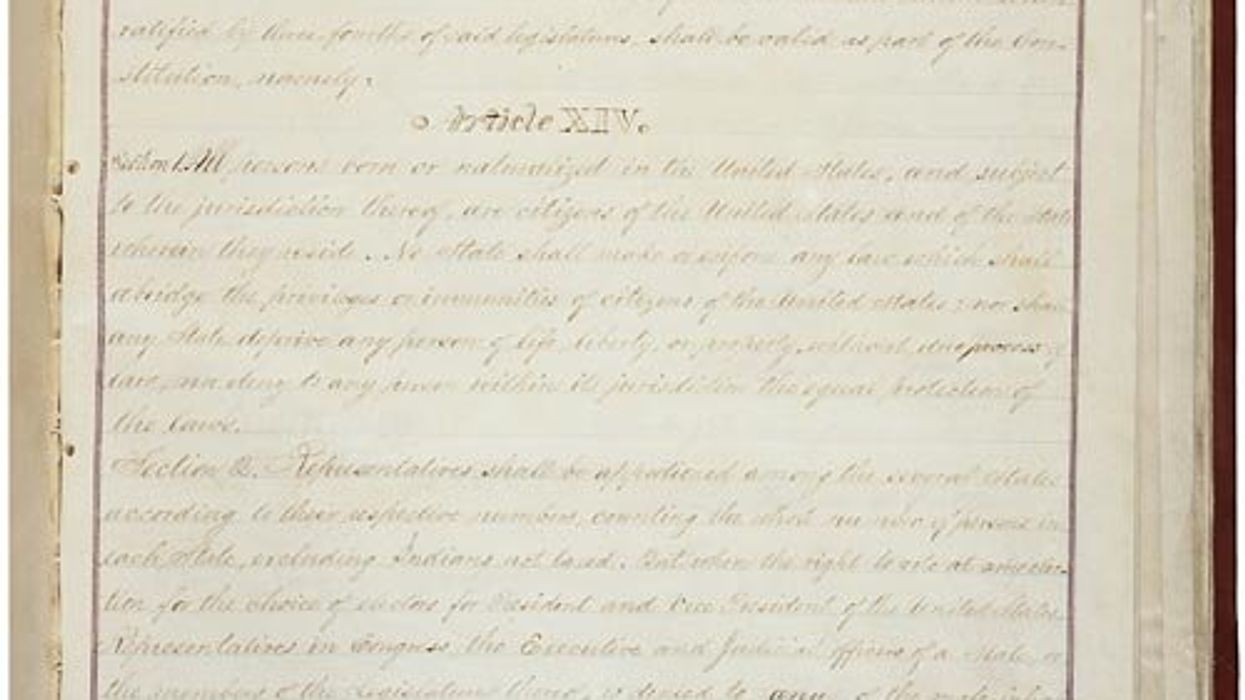

In the late 1860s, when the 14th Amendment was written and ratified, the same was true – though the right to vote was limited to men until 1920, and states have often denied or abridged the voting rights of some citizens, particularly racial minorities. After the Civil War, Congress sought to remove barriers to Black men’s voting, especially in the South.

In 1866, when Congress debated the 14th Amendment, its drafters wrote Section 2 in an effort to force reluctant white Southerners to allow Black men to vote.

Section 2 of the 14th Amendment provides that “ when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States … is denied … or in any way abridged … the basis of representation” for that state in the U.S. House of Representatives “shall be reduced” in proportion to the abridgment.

So if a state took away the voting rights of any of its citizens, it would immediately lose the same percentage of seats in the House as the percentage of people whose right to vote was taken away.

Just weeks after ratification, this provision faced its first challenge.

The Republican-dominated Reconstruction Legislature of Florida decided to choose presidential electors without a popular election. Democrats – at the time, the party supporting the disenfranchisement of Black men – were apoplectic. Many Southern newspaper writers, still angry about the ratification of the 14th Amendment, saw an opportunity to turn the amendment against its Republican authors.

“ The plain conclusion is that if in any State the election of Presidential electors is taken out of the hands of the people and placed in the hands of the Legislature, the whole number of citizens of the State … will be excluded,” wrote the Charleston Daily News on Aug. 10, 1868.

This was not a rare or local view: Nine days later, the Anderson Intelligencer, a South Carolina newspaper, published a short article credited to the New York Herald, similarly declaring:

“ When the right of voting for Presidential electors is denied to all voters of a State, then the basis of representation in such State must be reduced by the number of all the voters, which is to say that it is to have no basis of representation at all.”

These opinion articles have no legal authority, but they reflect a common – though contested – understanding of the 14th Amendment’s provisions at the time of its passage. No one brought a legal challenge, so no court had an opportunity to issue an opinion. And the Republican-dominated Congress had no qualms about accepting electoral votes – even without a popular vote – for the Republican presidential candidate.

The right to have your vote counted

In the wake of the 2020 election, Congress took steps to make clear that the voters must be the ones who choose presidential electors. Legislation passed in 2022 revised the federal law governing the selection of electors to specify that state legislatures must determine their state’s method of choosing electors before Election Day and can’t change it after the votes are cast.

That clarification lines up with – and indeed reinforces – the provisions of Section 2 of the 14th Amendment.

As our analysis notes, if a state legislature were to directly choose electors, that would disenfranchise all of the state’s voters. The right to vote, after all, is the right to have one’s vote counted, not the right to have one’s preferred candidate win.

So even if the legislature chose a slate of electors that received significant support in the popular election, the act of the legislature making the choice would abridge the rights of every voter in the state. Disenfranchisement depends on whether the people or the legislature chooses the electors, not which electors are selected.

If all of a state’s voters have their right to vote taken away, Section 2 requires that the state’s House representation immediately and automatically be reduced to zero. The Constitution elsewhere specifies that each state’s representation in the Electoral College is the sum of the state’s House and Senate delegations.

Thus, if a state has no representatives in the House, it would have only two presidential electors, rendering its influence over the presidential election minuscule and largely irrelevant.

A lone exception

To date, besides Florida in 1868, the only other instance of a state legislature choosing presidential electors without a popular election came in 1876.

Election fraud, political violence and voter intimidation undermined the integrity of the 1876 presidential election. The constitution of Colorado, newly admitted as a state, provided that the Legislature would choose the state’s presidential electors without a popular vote in 1876. Overshadowed by an exceptionally acrimonious election, the Legislature’s selection of Colorado’s presidential electors generated relatively little attention or debate.

The overall conclusion is that the Southern newspapers in 1868 correctly read the text of Section 2. The writers may have been cynical opportunists working to defend an indefensible racist hierarchy, but their interpretation of the text is sound.

The plain meaning of Section 2 is clear, and it imposes strong penalties if a state does not allow its citizens to vote for presidential electors. The 14th Amendment continues to protect American democracy more than 150 years after its ratification.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.