Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair of Political Science at Skidmore College and author of “ A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law.”

Real violence erupted at a presidential campaign rally on Saturday night. Rare though it was, it was still a sickening sight.

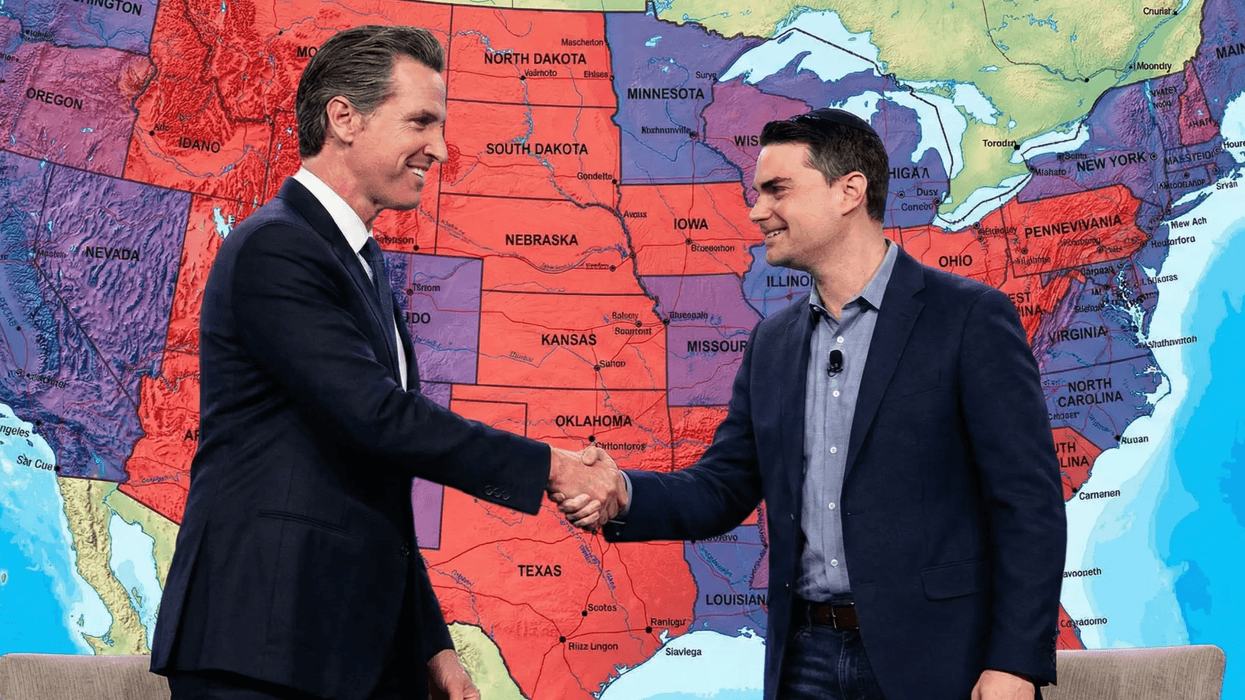

Tragically, metaphorical violence as part of campaign speeches is not at all rare. Democrats and Republicans — Biden and Trump, Harris and Haley, DeSantis and Kennedy, you name it — throw around allusions to violence as if we are currently engaged in some domestic incursion.

How often have we heard presidential candidates exclaim, “We are fighting for the soul of America” or battling “the opposition’s assault on democracy”? How frequently have our leaders implored us to “wage war against the foes of women’s freedom” or in defense of “the innocent life of an unborn child”? Of course, my favorite metaphor du jour is the “ weaponization ” of institutions and actions. Republicans talk of the weaponization of America’s legal system and of the left’s “woke” principles, while Democrats talk of the weaponization of impeachment efforts and family laptops. It has to stop.

The language of violence is not new to American politics. But it has taken on heightened consequences because of our current polarized state. Leaders on both sides of the aisle (along with the media) are simply too nonchalant about encouraging their followers to “fight, fight, fight.” The world feels somehow different today than when Ronald Reagan would occasionally invoke the battle metaphor (remember the “war on drugs”?) or when Bill Clinton would reference the “fight for farmers and the fight for accessible health care.”

Survey after survey shows that Americans are exhausted. The constant exposure to political intransigence and partisan bickering has drained our emotional reserves. It has also damaged Americans' faith in the government, their confidence in its leaders and our general sense of national pride.

Make no mistake: There should be no blaming the victim here. What happened to Donald Trump in Butler, Pa., is tragic and indefensible. A chorus of lawmakers past and present have condemned the actions of this apparently lone gunman. Many have echoed President Joe Biden’s sentiment that “there is no place in America for this kind of violence.” Agreed. But, equally, there should be no place in American politics for the sort of violent language that so easily passes the lips of those in power.

My plea to politicians on both the left and the right is to erase the violent vernacular from your messaging. Talk of restoring America to a progressive vision or a conservative ideal, not of destroying the opposite party. Speak of rebuilding the country to its rightful standing as the paragon of liberty, freedom, equality and justice, not of razing all policies initiated by representatives from across the aisle. Instead of the impulse to vilify, tell of your plans for renewal and rebirth, as Lincoln did. And FDR, and Johnson, and Reagan, and Obama.

Americans are fortunate. We inhabit a polity where liberty is valued above all else. The First Amendment to the Constitution safeguards these candidates and their messages. It should. Their remarks are rightly recognized as political speech, the loftiest and most revered variety of free expression. But as with all protected speech, the freedom to express oneself is not equivalent to the moral necessity to say anything that comes to mind. In other words, because some messages are protected does not mean they should be uttered. This is not a case of “one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric.” Surely, we can still get our most complex, nuanced and inspirational points across with a far less violent tone.

Democrats and Republicans alike should come together in prayer for Donald Trump’s swift and full recovery. Once that’s assured, we should renew the campaign for the presidency. Let it be vigorous, spirited, courageous and ardent. But, please, please let it also be rhetorically peaceful.