The U.S. prison system faces criticism for its failure to effectively rehabilitate incarcerated individuals, contributing to high recidivism rates. While some programs exist, they are often inadequate and lack sufficient resources, with many prisoners facing dangerous conditions and barriers to successful reintegration.

Alexis Tamm investigates, in a two-part series, the problems and responses to the significant obstacles recently released individuals face.

In Part 2, Alexis explores how a program is not only personally transformative for its participants, but it has the potential to fuel revolutionary change in how the U.S. addresses recidivism and reentry.

“We’re going to get people into careers they want—and stay with them until they can stand on their own,” Evie Litwok said of the Art of Tailoring in an interview with QNS. “What we’re doing is transformative.”

However, the program is not only personally transformative for its participants; it also has the potential to drive revolutionary change in how the U.S. addresses recidivism and reentry.

Along with personal impacts, the Art of Tailoring has large-scale economic benefits. While putting a student through the two-year program costs $12,500, detaining someone in Rikers Island costs $556,539 a year per person as of 2021—amounting to $1,525 a day. The same holds true for similar initiatives across the state; reentry and alternative-to-incarceration (ATI) programs save New York's correctional facilities more than $100 million a year. A 2016 study found an economic benefit of $3.46 to $5.54 for every dollar invested in such community-based programs.

Despite its benefits, Litwok is the first to admit that the Art of Tailoring cannot meet all the needs of its participants single-handedly. “For about $6,000 a year, for a total of two years, I can put somebody into business,” she said. “But that does not include stipends, and providing dinner, you know, providing a meal, or providing a metro card. This is the cost of teaching.”

System-impacted individuals often lack access to basic necessities such as food, shelter, and transportation—the very factors that frequently drive recidivism—and the Art of Tailoring can’t yet provide such assistance. “There are far more people who are in shelters that can be helped and should be helped with a support program. When you give out a grant to teach the Art of Tailoring, you also have to provide stipends to cover their expenses, including transportation and food. You can’t think straight if you’re hungry, and almost every person coming to that class is hungry,” Litwok said. “They have to miss a class if they’re working, they have to miss a class if they don’t have a metro card, they have to miss a class if they’re hungry and have to go somewhere to pick up food for themselves. So, without creating a safety net, you’re basically assuring the more privileged kids, who can get loans, are successful, and kids who have no money can’t be successful.”

While emphasizing the importance of vocational training, such as the Art of Tailoring, Litwok stresses that it can’t solve the problem alone. “If you can’t get the basic support of, in my opinion, stipends, food, and transportation covered, you can’t succeed.”

Like-minded organizations in NYC are striving to provide a wider array of necessities for the formerly incarcerated, such as The Fortune Society, a Queens-based nonprofit taking a holistic approach to reentry services and alternatives to incarceration. Similar to the Art of Tailoring, the Fortune Society’s Employment Services program offers specialized job training in areas such as culinary arts, sustainable construction and building maintenance, and transportation, as well as opportunities for short-term transitional work to gain employment experience. However, they also provide a range of services to address needs that such training may not cover, including transitional and long-term housing options, daily meals and nutrition education, connections to health services, and access to mental health and substance use treatment, among others. They proudly served 13,377 individuals in 2024, including nearly 600 participants enrolled in their employment training services and over 1,000 individuals to whom they provided housing, helping them rebuild successful lives after incarceration.

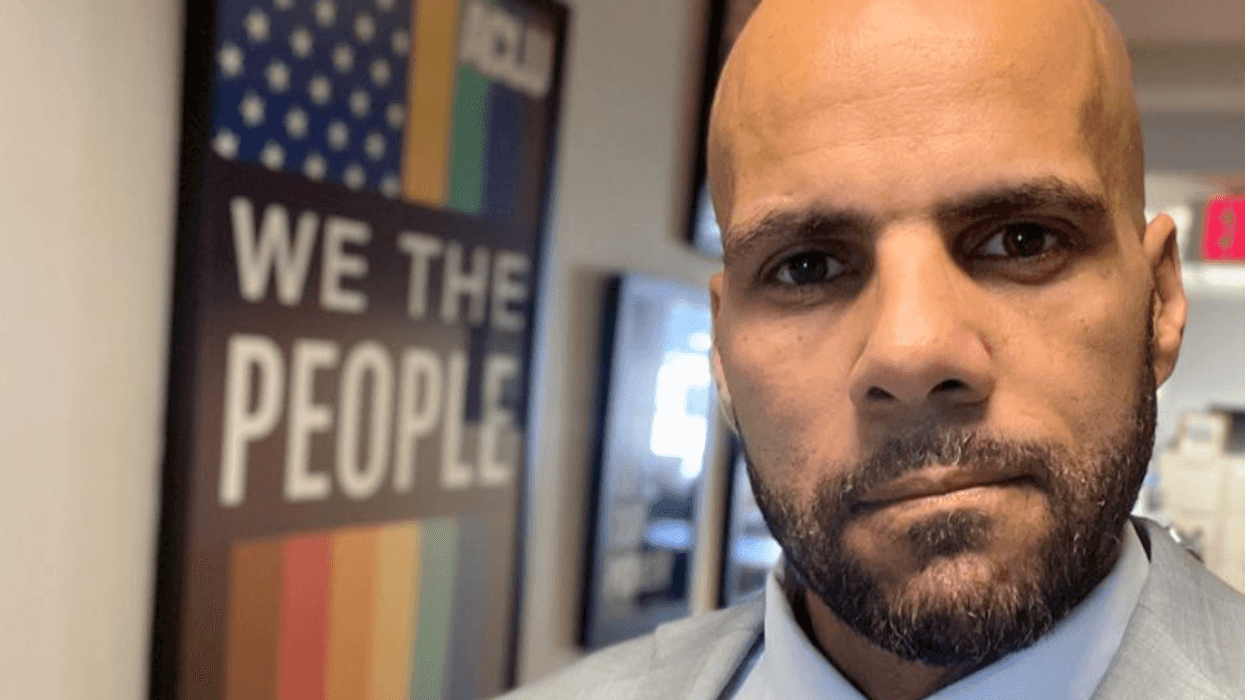

“We have demonstrated proof of concept in New York City that ATI and reentry services not only help people get out and stay out of jail and prison but also move on with their lives and support their families and communities,” Stanley Richards, President and CEO of the Fortune Society and formerly incarcerated individual himself, said in response to a 2024 report by the New York State Alternatives to Incarceration and Reentry Coalition.

More broadly, the benefits of such ATI programs are increasingly being recognized. New York State Senator Julia Salazar, Chair of the Committee on Crime Victims, Crime and Correction, is an advocate for prison reform and is currently fighting for the rights of incarcerated individuals. “If New York State has a duty to keep ALL its residents safe, we must end our reliance on incarceration as the solution to our social problems,” Salazar said in reaction to the same New York report. “On release, formerly incarcerated people are positioned at great socioeconomic disadvantage without supports in place to address their unique needs. We can end mass incarceration and keep our communities safe if we invest in proven programs and compassionate care.”

The Art of Tailoring’s students have already started to see success only a few months into the program, sporting their latest designs in their own fashion show at the Youth Pride Fest at Pier 76 on June 7th—one of the many events Witness is participating in this Pride Month to celebrate and garner support for the LGBTQ+ system-impacted community. Litwok and the organization were also honored at the SunnyPride celebration in Queens on June 13th for their anti-recidivism work, a testament to Witness’s dedication to its mission.

“On the one hand, you’re giving them something they can do, and if they can earn a living, they’ll never be in your system. It won’t reduce recidivism, it will eliminate recidivism,” Litwok said of system-impacted individuals. “On the other hand, if you send a kid to Rikers for some minor thing or any reason, you’re going to damage them for life. So, which option do you like?”

SUGGESTION: Reducing Recidivism, One System-Impacted Entrepreneur at a Time

a long hallway with a bunch of lockers in it Photo by Matthew Ansley on Unsplash

a long hallway with a bunch of lockers in it Photo by Matthew Ansley on Unsplash

Alexis Tamm is a senior at Georgetown University. An avid writer and aspiring journalist, she is passionate about solutions-focused reporting and driving change through storytelling.

Alexis was a cohort member in Common Ground USA's Journalism program, where Hugo Balta served as an instructor. Balta is the executive editor of the Fulcrum and the publisher of the Latino News Network.

The Fulcrum is committed to nurturing the next generation of journalists. Learn more by clicking HERE.