Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

In the first installment of this two-part series, I focused on the many efforts that failed to roll back the popular vote-by-mail options to pre-pandemic levels and the GOP effort to disqualify more ballots. Today we focus on the states in the crosshairs.

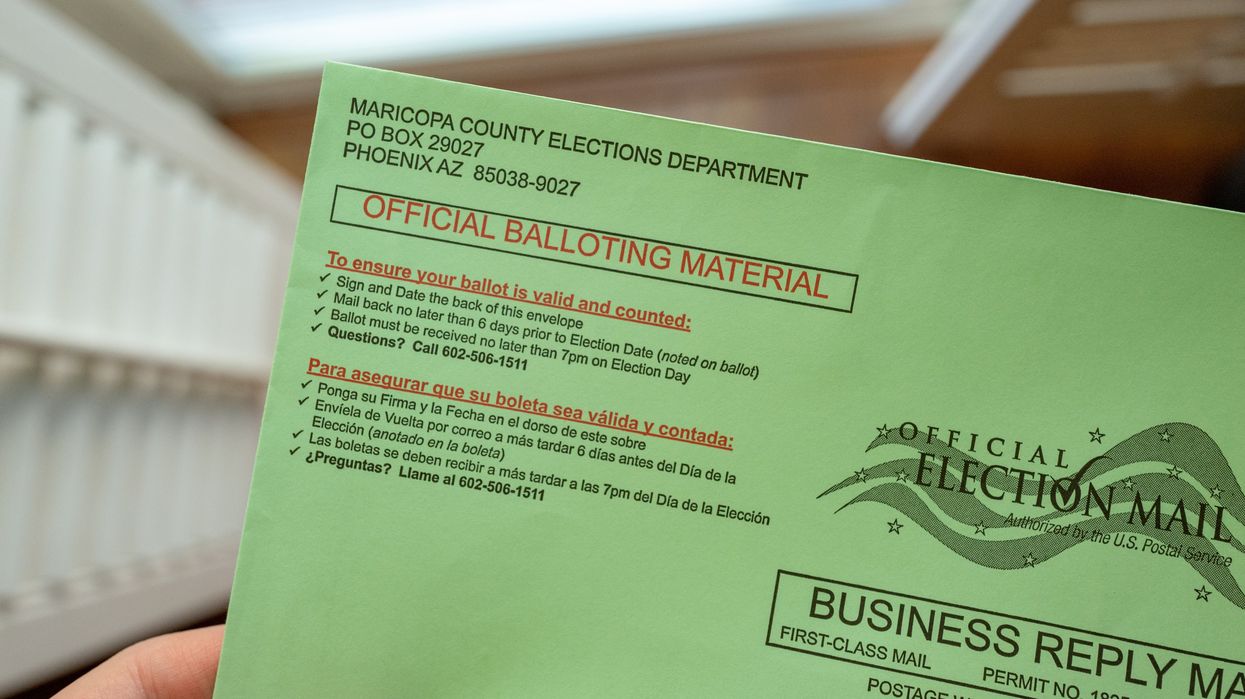

The litigation targeting mailed-out ballots has evolved since the 2020 and 2022 general elections, when Trump-supporting Republicans lost many federal and statewide contests, and their allies took broad swipes at vote-by-mail programs. Take Arizona, for example, whose current mail voting regime has been in place since 1991, and where 80 percent of its statewide electorate cast mail ballots in 2020’s presidential election.

In mid-2023, the Arizona Supreme Court rejected a state Republican Party lawsuit seeking to ban the option. A suit filed by right-wing activists to ban ballot drop boxes was rejected in April 2024. As a result of decisions like these, more recent litigation has turned to contesting technicalities. But that, too, is not succeeding — at least not in Arizona.

A suit from activists challenging Arizona’s signature matching rules (to verify a voter’s identity based on how they sign the return envelope) was dismissed in April, but has been appealed. Another suit seeking to match signatures on the envelopes with voters’ registration forms — not the most recent election records — was dismissed in June. As a result, voting by mail in Arizona is largely unchanged.

But states where voting by mail was dramatically expanded in the pandemic — especially other presidential battleground states — have seen even more fractious lawfare.

Wisconsin

After 2020’s election, Wisconsin Republicans sued over ballot drop boxes, and the state’s conservative-majority Supreme Court banned them. But after liberals gained a majority on the court in August 2023, liberal advocates sued and won a suit to reinstate their use. Then, as was the case in Arizona, Wisconsin’s Republicans turned to the process’s fine print.

In Wisconsin, voters casting mail ballots must have a witness sign their return envelope. Liberals hoped to overturn that requirement but lost a federal suit to do so. At the same time a suit filed by right wing activists in state court challenged a directive that allowed election officials to fill in missing identifying information for witnesses. That suit evolved into a lengthy court fight over what address information could be used by officials to verify a witness’s identity. In September, a court ruled local officials could use the information in their voter registration database.

Pennsylvania

But no state has seen as much litigation targeting the process’s fine print and minutiae — from both parties and their allies — as Pennsylvania.

This fall, one swing county – Luzerne, in the state’s northeast — was not planning to deploy drop boxes. Voting rights advocates sued on Oct. 1 to force their use and county officials backed down for this fall. Liberals also sued in state court in September to reverse past rulings disqualifying ballots in wrongly dated or undated return envelopes. On Oct. 5, the state Supreme Court denied their petition on procedural grounds, not merits — which was a setback for more inclusive voting. Another suit was filed in April to push counties to offer voters an alternative way to vote if their ballot wasn’t placed inside a special sleeve inside the return envelope (which, under other state law, would disqualify the ballot). That suit is now before the state’s Supreme Court.

As dizzying as this sounds, it is not all of the Pennsylvania litigation. Republican lawmakers lost a suit to ban voters from returning mail ballots to county election offices. (They wanted to limit voters to voting sites.) The Republican Party sued in September to bar counties from using different protocols to help voters “cure” mistakes on their return envelopes. The state’s Supreme Court rejected that suit in October, citing a “lack of due diligence” to file earlier. However, the court has agreed to take up a suit by liberals to ensure that voters be given a chance to cure errors.

This blur of litigation is due to several factors. In 2019, Pennsylvania passed sweeping election reforms, including universal mail-in voting. That was before the pandemic, where the state expanded that option to protect public health. Then, in 2020, and again in 2024, Pennsylvania was among the nation’s presidential battleground states. The National Vote at Home Institute’s Smith Wagner and other experts also said that Pennsylvania’s courts have issued a lot of conflicting rulings on the details of voting by mail.

“Whenever new legislation is enacted, there’s always a period of litigation to work out wrinkles that may be ambiguous in the text, things like that,” said Emma Shoucair, a voting rights attorney with RepresentUs, a nonpartisan anti-corruption group. “However, some of the conflict has been due to the fact that the intermediate court that has jurisdiction over a lot of election matters (the Commonwealth Court) has been majority Republican, while the Supreme Court has been majority Democrat (although the Commonwealth Court has begun to shift very recently). You’re also seeing some differences of opinion, especially on the provision of Act 77 requiring the voter to date the ballot, between various panels of the Third Circuit (the federal appeals court). So, there is a lot going on.”

Most of this litigation will not affect voters who cast mailed-out ballots, she said. But Shoucair was watching whether voters who made a mistake on their ballot envelopes could vote with a provisional ballot — which undergoes additional verification before being counted.

She and other experts, including former Pennsylvania Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar, who oversaw the state’s 2020 election, urged voters to ignore the legal noise and vote early.

“With all the confusing noise of the back-and-forth litigation on mail ballots, the most important message for PA voters is actually very simple — ignore the noise!” she said. “Just remember three things that you must do to have your vote counted: 1) put your marked ballot inside the inner yellow secrecy envelope and insert the secrecy envelope into the outer addressed envelope; 2) sign your name and put TODAY'S DATE on the outer envelope — not your birth date; and 3) don't wait! If you want to vote by mail, submit your application immediately, complete your ballot as described, and mail it or drop off at one of your county voting locations immediately.”

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne