Anderson edited "Leveraging: A Political, Economic and Societal Framework" (Springer, 2014), has taught at five universities and ran for the Democratic nomination for a Maryland congressional seat in 2016.

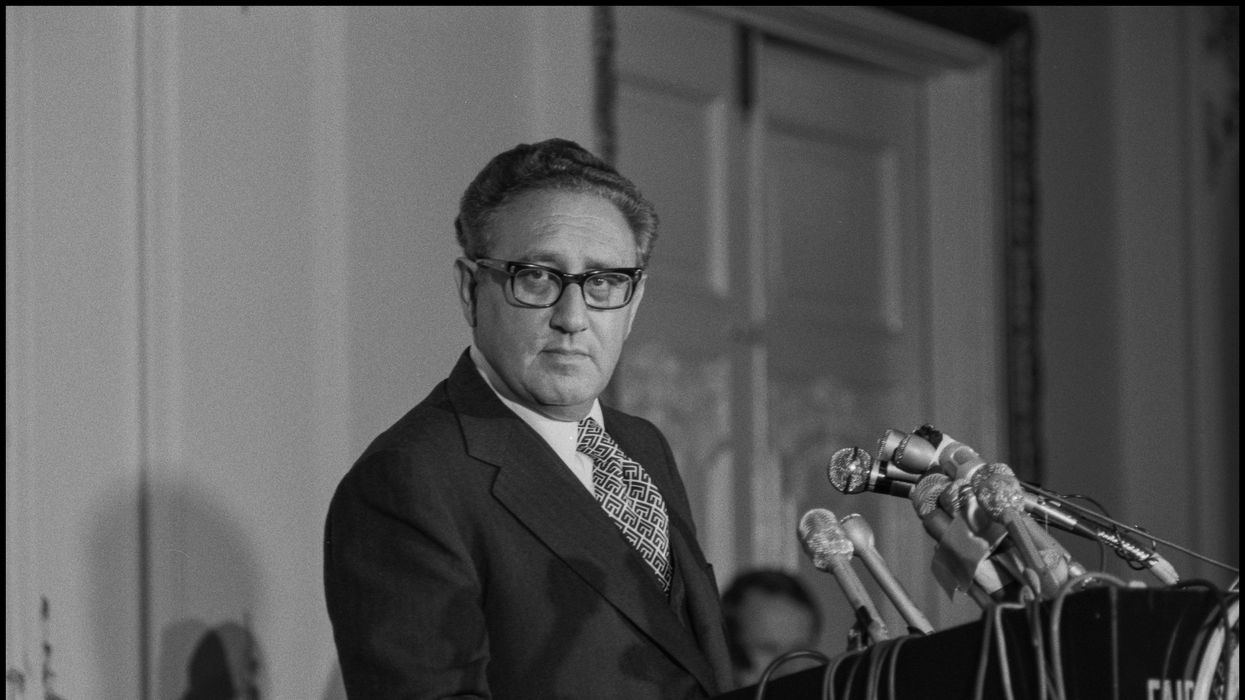

The death of Henry Kissinger at 100 has naturally led to two related debates. First, was the former national security advisor and secretary of state, serving Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, successful in his work? Second, what was his approach in foreign policy and international affairs?

The typical answer given to the second question is that Kissinger was a realist and not an idealist (or liberal internationalist). The typical answer to the first question is that Kissinger was successful in his work, although he certainly had his flaws. Kissinger typically is therefore regarded as a master of realpolitik. He worked to open the door to Red China, achieve detente with the Soviet Union and end the war in Vietnam. There are dissenters, especially those who accuse him of war crimes – notably for secretive bombings in Cambodia.

The debates will go on for years, but it would be helpful if the discussion about whether Kissinger was a realist identified three main possibilities for understanding his work and not two. The question to be answered is whether Kissinger was a realist, an idealist or a pragmatist. Pragmatism in the tradition of John Dewey, widely regarded as America's greatest philosopher, has received more attention in the last 20 years of international relations theory in academia. It is well behind constructivism, which has established itself as a viable alternative to both realism and idealism. But in discussions of foreign policy itself rather than academic IR theory the terms pragmatism and pragmatic are used freely, certainly in both the news media and the opinion page media.

In 1979, the noted political scientist John Stoessinger published “Crusaders and Pragmatists: Movers of Modern American Foreign Policy,” which divided presidents into two categories based on their foreign policies: the idealists and the pragmatists. Nixon was regarded as a pragmatist, whereas Woodrow Wilson was regarded as the classic idealist.

Kissinger therefore was part of a pragmatist effort to create a new, essentially triangular world order where the United States, the Soviet Union and China could coexist peacefully. Kissinger's shuttle diplomacy with China, designed to calm relations with the Soviets, was interpreted by Stoessinger as pragmatic in a broad sense of the term.

Realism in academia, notably represented by major thinkers like Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz and (certainly balance-of-power 19th century realism as practiced by politicians like Germany's Otto von Bismarck), revolves around the concepts of power and self-interest. States pursue power in order to advance their self-interest according to traditional realists. Wilsonian idealism, on the other hand, seeks to create an architecture in the world order that will make the world safe for democracy. Idealists like Wilson, author of the Fourteen Points and advocate for the League of Nations, or liberal internationalists like John Ikenberry today, are focused on the concepts of rule of law, democracy, peace and freedom, not power and self-interest.

Pragmatism in the American philosophical tradition, which has seen a revival since Richard Rorty published “Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature" (1979) and the "Consequences of Pragmatism” (1982), is also focused on concepts of rule of law, democracy, peace and freedom along with concepts of harnessing uncertainty and applying our best science to solve the “practical problems of men” in Dewey's words. Only a crude version of pragmatism would advocate taking actions in the foreign policy arena where the ends justify whatever means are necessary.

Kissinger, a Harvard trained political scientist and faculty member, was a brilliant theoretician and a brilliant practitioner. He and Nixon were the architects of a new world order that would enable capitalism and communism to peacefully coexist, and he was the primary practitioner who did the negotiating to implement their plan. Calling him a realist, even a master realist, or a principled realist (an academic attempt to save realism from its negative implications), imposes a simplistic taxonomy on a complicated public servant.

Stoessinger no doubt oversimplified our presidents by dividing them into idealists and pragmatists. The debate that is needed about Kissinger, which could help academics and their graduate students, is whether he was more of an idealist, a realist or a pragmatist. The evaluative question will remain, namely whether he was a successful idealist, a successful realist or a successful pragmatist.

Eric Trump, the newly appointed ALT5 board director of World Liberty Financial, walks outside of the NASDAQ in Times Square as they mark the $1.5- billion partnership between World Liberty Financial and ALT5 Sigma with the ringing of the NASDAQ opening bell, on Aug. 13, 2025, in New York City.

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?

Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche joined ABC’s “This Week” on Sunday to defend or explain a lot of controversies for the Trump administration: the Epstein files release, the events in Minneapolis, etc. He was also asked about possible conflicts of interest between President Trump’s family business and his job. Specifically, Blanche was asked about a very sketchy deal Trump’s son Eric signed with the UAE’s national security adviser, Sheikh Tahnoon.

Shortly before Trump was inaugurated in early 2025, Tahnoon invested $500 million in the Trump-owned World Liberty, a then newly launched cryptocurrency outfit. A few months later, UAE was granted permission to purchase sensitive American AI chips. According to the Wall Street Journal, which broke the story, “the deal marks something unprecedented in American politics: a foreign government official taking a major ownership stake in an incoming U.S. president’s company.”

“How do you respond to those who say this is a serious conflict of interest?” ABC host George Stephanopoulos asked.

“I love it when these papers talk about something being unprecedented or never happening before,” Blanche replied, “as if the Biden family and the Biden administration didn’t do exactly the same thing, and they were just in office.”

Blanche went on to boast about how the president is utterly transparent regarding his questionable business practices: “I don’t have a comment on it beyond Trump has been completely transparent when his family travels for business reasons. They don’t do so in secret. We don’t learn about it when we find a laptop a few years later. We learn about it when it’s happening.”

Sadly, Stephanopoulos didn’t offer the obvious response, which may have gone something like this: “OK, but the president and countless leading Republicans insisted that President Biden was the head of what they dubbed ‘the Biden Crime family’ and insisted his business dealings were corrupt, and indeed that his corruption merited impeachment. So how is being ‘transparent’ about similar corruption a defense?”

Now, I should be clear that I do think the Biden family’s business dealings were corrupt, whether or not laws were broken. Others disagree. I also think Trump’s business dealings appear to be worse in many ways than even what Biden was alleged to have done. But none of that is relevant. The standard set by Trump and Republicans is the relevant political standard, and by the deputy attorney general’s own account, the Trump administration is doing “exactly the same thing,” just more openly.

Since when is being more transparent about wrongdoing a defense? Try telling a cop or judge, “Yes, I robbed that bank. I’ve been completely transparent about that. So, what’s the big deal?”

This is just a small example of the broader dysfunction in the way we talk about politics.

Americans have a special hatred for hypocrisy. I think it goes back to the founding era. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed in “Democracy In America,” the old world had a different way of dealing with the moral shortcomings of leaders. Rank had its privileges. Nobles, never mind kings, were entitled to behave in ways that were forbidden to the little people.

In America, titles of nobility were banned in the Constitution and in our democratic culture. In a society built on notions of equality (the obvious exceptions of Black people, women, Native Americans notwithstanding) no one has access to special carve-outs or exemptions as to what is right and wrong. Claiming them, particularly in secret, feels like a betrayal against the whole idea of equality.

The problem in the modern era is that elites — of all ideological stripes — have violated that bargain. The result isn’t that we’ve abandoned any notion of right and wrong. Instead, by elevating hypocrisy to the greatest of sins, we end up weaponizing the principles, using them as a cudgel against the other side but not against our own.

Pick an issue: violent rhetoric by politicians, sexual misconduct, corruption and so on. With every revelation, almost immediately the debate becomes a riot of whataboutism. Team A says that Team B has no right to criticize because they did the same thing. Team B points out that Team A has switched positions. Everyone has a point. And everyone is missing the point.

Sure, hypocrisy is a moral failing, and partisan inconsistency is an intellectual one. But neither changes the objective facts. This is something you’re supposed to learn as a child: It doesn’t matter what everyone else is doing or saying, wrong is wrong. It’s also something lawyers like Mr. Blanche are supposed to know. Telling a judge that the hypocrisy of the prosecutor — or your client’s transparency — means your client did nothing wrong would earn you nothing but a laugh.

Jonah Goldberg is editor-in-chief of The Dispatch and the host of The Remnant podcast. His Twitter handle is @JonahDispatch.