Sanfilippo is an assistant professor in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and book series editor for Cambridge Studies on Governing Knowledge Commons. She is a public voices fellow of The OpEd Project.

Deepfakes of celebrities and misinformation about public figures might not be new in 2024, but they are more common and many people seem to grow ever more resigned that they are inevitable.

The problems posed by false online content extend far beyond public figures, impacting everyone, including youth.

New York Mayor Eric Adams in a recent press conference emphasized that many depend on platforms to fix these problems, but that parents, voters and policymakers need to take action. “These companies are well aware that negative, frightening and outrageous content generates continued engagement and greater revenue,” Adams said.

Recent efforts by Taylor Swift’s fans, coordinated via #ProtectTaylorSwift, to take down, bury, and correct fake and obscene content about her are a welcome and hopeful story about the ability to do something about false and problematic content online.

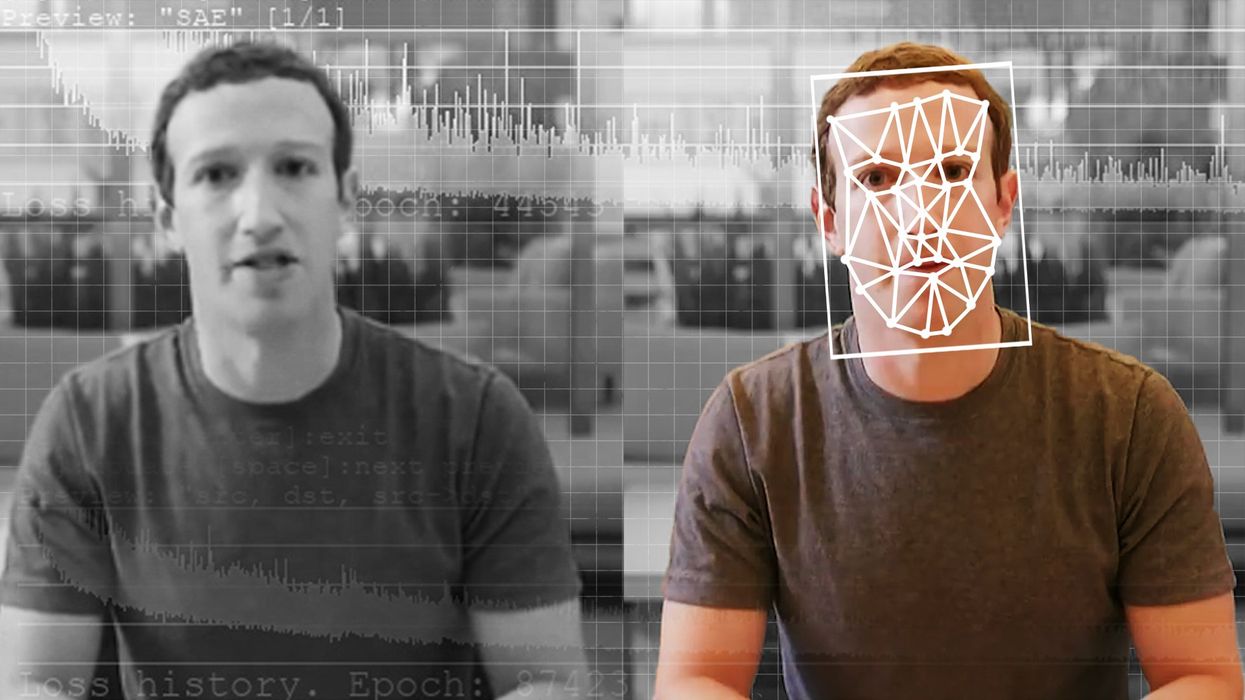

Still, deepfakes (videos, photos and audio manipulated by artificial intelligence to make something look or sound real) and misinformation have drastically changed social media over the past decade, highlighting the challenges of content moderation and serious implications for consumers, politics and public health.

At the same time, generative AI — with ChatGPT at the forefront — changes the scale of these problems and even challenges digital literacy skills recommended to scrutinize online content, as well as radically reshaping content on social media.

The transition from Twitter to X — which has 1.3 billion users — and the rise of TikTok — with 232 million downloads in 2023 — highlight how social media experiences have evolved as a result.

From colleagues at conferences discussing why they’ve left LinkedIn and students asking if they really need to use it, people recognize the decrease in quality of content on that platform (and others) due to bots, AI and the incentives to produce more content.

LinkedIn has established itself as key to career development, yet some say it is not preserving expectations of trustworthiness and legitimacy associated with professional networks or protecting contributors.

In some ways, the reverse is true: User data is being used to train LinkedIn Learning’s AI coaching with an expert lens that is already being monetized as a “professional development” opportunity for paid LinkedIn Premium users.

Regulation of AI is needed as well as enhanced consumer protection around technology. Users cannot meaningfully consent to use platforms and their ever changing terms of services without transparency about what will happen with an individual’s engagement data and content.

Not everything can be solved by users. Market-driven regulation is failing us.

There needs to be meaningful alternatives and the ability to opt out. It can be as simple as individuals reporting content for moderation. For example, when multiple people flag content for review, it is more likely to get to a human moderator, who research shows is key to effective content moderation, including removal and appropriate labeling.

Collective action is also needed. Communities can address problems of false information by working together to report concerns and collaboratively engineer recommendation systems via engagement to deprioritize false and damaging content.

Professionals must also build trust with the communities they serve, so that they can promote reliable sources and develop digital literacy around sources of misinformation and the ways AI promotes and generates it. Policymakers must also regulate social media more carefully.

Truth matters to an informed electorate in order to preserve safety of online spaces for children and professional networks, and to maintain mental health. We cannot leave it up to the companies who caused the problem to fix it.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift