Lynn Greenky is an Associate Professor of Communication and Rhetorical Studies at Syracuse University.

Elon Musk has claimed he believes in free speech no matter what. He calls it a bulwark against tyranny in America and promises to reconstruct Twitter, which he now owns, so that its policy on free expression “ matches the law.” Yet his grasp of the First Amendment – the law that governs free speech in the U.S. – appears to be quite limited. And he’s not alone.

I am a lawyer and a professor who has taught constitutional concepts to undergraduate students for over 15 years and has written a book for the uninitiated about the freedom of speech; it strikes me that not many people educated in American schools, whether public or private – including lawyers, teachers, talking heads and school board members – appear to have a working knowledge about the right to free speech embedded in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

But that doesn’t have to be the case.

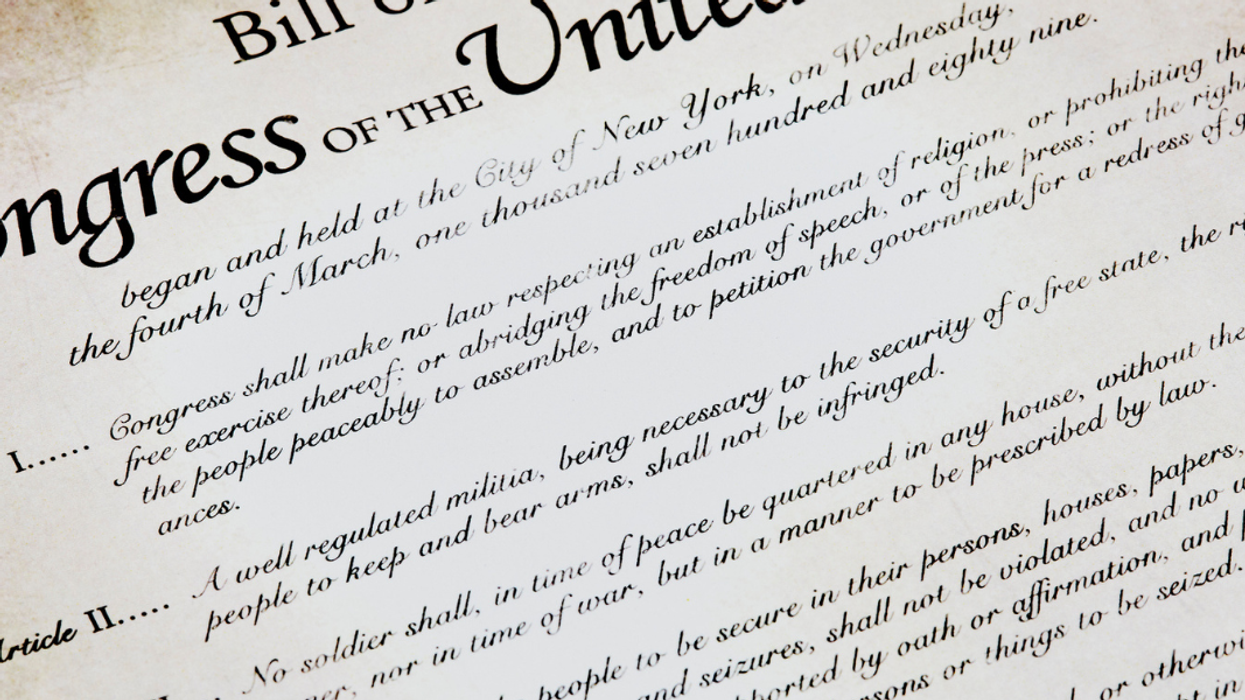

In short, the First Amendment enshrines the freedom to speak one’s mind. It’s not written in code and does not require an advanced degree to understand. It simply states: “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech.” The liberties embraced by that phrase belong to all of us who live in the United States, and we can all become knowledgeable about their breadth and limitations.

There are just four essential principles.

1. It’s only about the government

The Bill of Rights – the other name for the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution – like the Constitution itself and all the other amendments, sets limits only on the relationship between the U.S. government and its people.

It does not apply to interactions in other nations, nor interactions between people in the U.S. or companies. If the government is not involved, the First Amendment does not apply.

The First Amendment ensures that Twitter is, in fact, free of government restrictions against spreading misinformation and disinformation or virtually anything else. The company is similarly free to expel any users who offend Musk’s personal sensibilities. They can be booted off Twitter and any charges of “Censorship!” don’t apply.

2. For decades, speech has faced very few limits

Freedom of expression was understood by the nation’s founders to be a natural, unalienable right that belongs to every human being.

Over the course of the first 120-plus years of the country’s democratic experiment, judicial interpretation of that right slowly evolved from a limited to an expansive view. In the middle of the 20th century, the Supreme Court ultimately concluded that because the right to speak freely is so fundamental, it is subject to restriction only in limited circumstances.

It is now an accepted doctrine that tolerance for discord is built into the very fabric of the First Amendment. In the words of one of the most revered Supreme Court justices, Louis D. Brandeis, “ it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; … fear breeds repression; … repression breeds hate; … hate menaces stable government.”

Opinions, viewpoints and beliefs – which are sometimes based on provable fact, other times on hypothetical theories and occasionally on lies and conspiracies – all contribute to what constitutional scholars and lawyers refer to as the “ marketplace of ideas.” Similar to the commercial marketplace, the marketplace of ideas subjects all products to competition. The hope is that only the best will survive.

Therefore, members of the Westboro Baptist Church can picket the funerals of fallen soldiers with signs disparaging the LGBTQ+ community, Nazi hate groups can hold rallies and civil rights groups can participate in lunch-counter protests. The ideas expressed by each of these groups represent one perspective in the public debate about rights and privileges, government responsibility and religion. Other people and groups may disagree, but their perspectives are also protected from government censorship and repression.

Messages communicated by means other than speech or writing are generally protected by the First Amendment, too. A jean jacket bearing the Vietnam-era anti-war slogan “ F*ck the Draft ” is protected, as is the act of burning a United States flag in front of a crowd. These were potentially more emotionally powerful than politely worded statements opposing government policies.

3. But not all speech is protected

The government does, in fact, have the power to regulate some speech. When the rights and liberties of others are in serious jeopardy, speakers who provoke others into violence, wrongfully and recklessly injure reputations or incite others to engage in illegal activity may be silenced or punished.

People whose words cause actual harm to others can be held liable for that damage. Right-wing commentator Alex Jones found that out when courts ordered him to pay more than US$1 billion in damages for his statements about, and treatment of, parents of children who were killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut.

So, abortion opponents can say what they wish but can’t threaten or terrorize abortion providers. And the white supremacists who rallied in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 can shout to the rafters that Jews will not replace them, but they can be held liable for the intimidation, harassment and violence they used to amplify their words.

Rules about incitement to illegal action are part of the U.S. Department of Justice’s investigation into whether former President Donald Trump is at all responsible for the violence at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. On that day, citing unproven, even disproved, events, Trump delivered a speech insisting the 2020 presidential election was rife with fraud.

However, the First Amendment doesn’t protect only true statements. Trump has a constitutional right to advocate for his perspective. Even his references to violence might be considered shielded from criminal prosecution by the superpower of the First Amendment. That superpower would evaporate only if a court finds that, when he spoke the words that day, “And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore,” his intent was to incite the violence that followed.

4. What’s legal isn’t always morally correct

Finally, and perhaps most importantly: Moral boundaries to acceptable speech are different, and often much narrower, than constitutional boundaries. They should not be conflated or confused.

The First Amendment right to speak freely as an exercise of people’s natural rights does not mean everything anyone says anywhere is morally acceptable. Constitutionally speaking, ignorant, demeaning and vitriolic speech – including hate speech – are all protected from government repression, even though they may be morally offensive to the majority.

Still, some people insist that malicious and emotionally hurtful speech adds no value to society. That is one reason used by people who seek to cancel or ban controversial speakers from college campuses.

Indeed, virulent speech may even weaken the democratic exchange of ideas, by discouraging some people from participating in public discussion and debate, to avoid potential harassment and scorn.

Nonetheless, that sort of speech remains firmly under the umbrella of First Amendment defenses. Each person must decide how their own humanity and morality allows them to speak for themselves.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift