Breslin is the Joseph C. Palamountain Jr. Chair of Political Science at Skidmore College and author of “A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law.”

The story is charming. It goes like this: Benjamin Franklin emerges from the Pennsylvania Statehouse — now Philadelphia’s Independence Hall — after four grueling months debating the design of a new constitutional text, and he is met at the door by a recognizable, and welcomed, figure.

Elizabeth Willing Powel was familiar to Franklin. A Philadelphia socialite, Powel had frequently mingled that summer with the likes of Madison, Hamilton, Morris, Washington, Franklin, and so many others. All were comfortable in her presence, and she in theirs. But that day Powel had an incisive, pointed question for the famous Philadelphian: “Well, Doctor,” she inquired, “what have we got? A Republic or a Monarchy”? Franklin’s legendary repose? “A Republic, if you can keep it.”

The tale of Franklin’s encounter with Powel has been passed down for generations; it is American folklore. And it’s probably fiction. Even so, the story has never been more relevant — more significant — than it is today, given how polarized and caustic our political environment is right now.

What Franklin uttered on that 17th day of September 1787 was prescient and cautionary. His response to Powel represented both a dash of hope at the onset of America’s political journey and a clear warning. Our republic — indeed, all republics — he seemed to be saying, are fragile. They require civic commitment, a sense of public solidarity, a degree of selflessness in the body politic and, perhaps most of all, meaningful citizen engagement.

Franklin was confident that his contemporaries could deliver, that members of the early republic would recall the famous pledge in the Declaration of Independence that the people of this new and independent America were willing to sacrifice “their Lives, their Fortunes, and their sacred Honor” for the public good. He was confident that members of the Founding generation could shoulder the weight of robust popular sovereignty. The Revolutionary War, he noted, was indicative of his generation’s dedication to the common cause of political self-determination. So was a written national Constitution, as well as the process of bringing to life that fundamental charter through popular ratification. His faith was justified.

Today, most do not share Franklin’s confidence. Too many American citizens are increasingly jaded, intensely frustrated and comparatively tuned out. “Voters overwhelmingly believe American democracy is under threat,” states The New York Times, “but [they also] seem remarkably apathetic about that danger.” Former Rep. Liz Cheney warns about the end of our republic. “The assumption that our institutions will protect themselves,” she said, “is purely wishful thinking by people who prefer to look the other way.”

Blame for our current political state is widespread; it can be placed at the feet of politicians, institutions, even “we, the people.” At its most basic, though, Americans are having trouble with definitions. There is a difference between political engagement and political participation. The former requires a certain depth of knowledge and a corresponding duty to invest in the future of the political community. No, political engagement does not demand that all citizens run for office or contribute to electoral campaigns. What it does require is humility, the recognition that there may be something bigger and more important than one’s own private interests. True political engagement is achieved only by taking seriously the ideas of others and admitting that those ideas may affect one’s own. Authentic political engagement does not exist in an echo chamber; it is thoughtful, reflective and unassuming.

In contrast, political participation only insists that citizens take a passive role, that they show up once a year at the ballot box and then retreat back to their ideological and partisan bunkers. Political participation, unlike genuine engagement, is transactional, where involvement in politics is seen as a kind of calculation centered on personal advancement (what can you do for me?) and tribal naysaying (members of the opposing party are all corrupt, immoral and stupid). It is shallow, thin and one-dimensional, a slight step above complete political apathy.

Franklin and the members of the early republic were politically engaged, while most present Americans are merely political participants. That dichotomy, I’d suggest, accounts for a good portion of our current political malaise. The question is, how can we flip the script? How can we recover some of the spirit of civitas that oozed from the Founding generation? To be sure, the Founders were not perfect. Far from it (they perpetuated slavery, after all). But they were democrats (with a small “d”) and they were republicans (with a small “r”).

We’re nostalgic for a time when political engagement was accepting — maybe even embracing — of the principles of concession, cooperation and compromise. When politics was less of a blood sport and more of an artform. When we had faith in our system and the officials operating it. Indeed, we crave what we don’t have: political stability, respectful discourse and genuine civility.

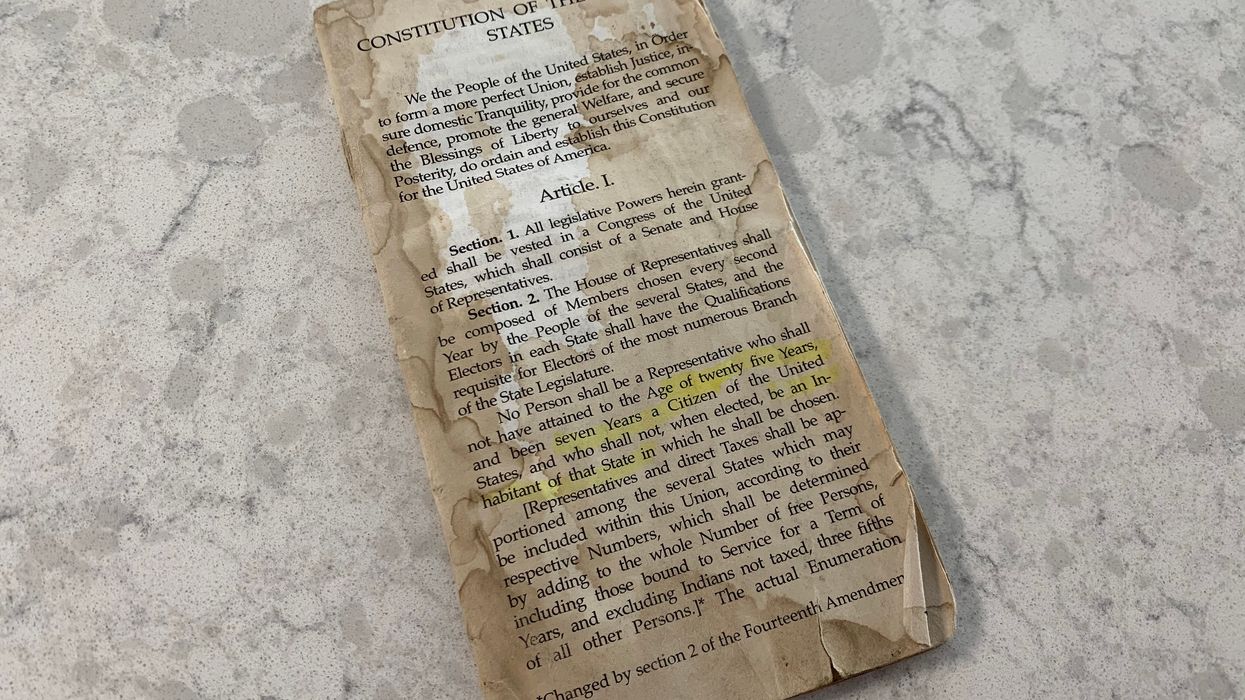

But lest we believe we are completely doomed I’d also suggest that there remains considerable optimism. The Constitution is, and always should be, our lodestar; it is both America’s stabilizing keel and its democratic inspiration. It is our last, best hope.

In a series of essays over the next many months, I will highlight claus es, components, principles and stories of America’s great charter. My goal is simple: to assist American citizens on the bumpy road ahead. And though I’m not so immodest as to think that my words will replace the political antacid we all covet, I am quite sure that the ideas embedded in our constitutional narrative are as vital and reassuring today as they’ve ever been.

Benjamin Franklin and the members of the Founding generation gifted us a republic, one that has mostly endured for almost a quarter millennium. Let’s try to keep it.