The chairman of the Federal Communications Commission is displeased with a broadcast network. He makes his displeasure clear in public speeches, interviews and congressional testimony.

The network, afraid of the regulatory agency’s power to license their owned-and-operated stations, responds quickly. They change the content of their broadcasts. Network executives understand the FCC’s criticism is supported by the White House, and the chairman implicitly represents the president.

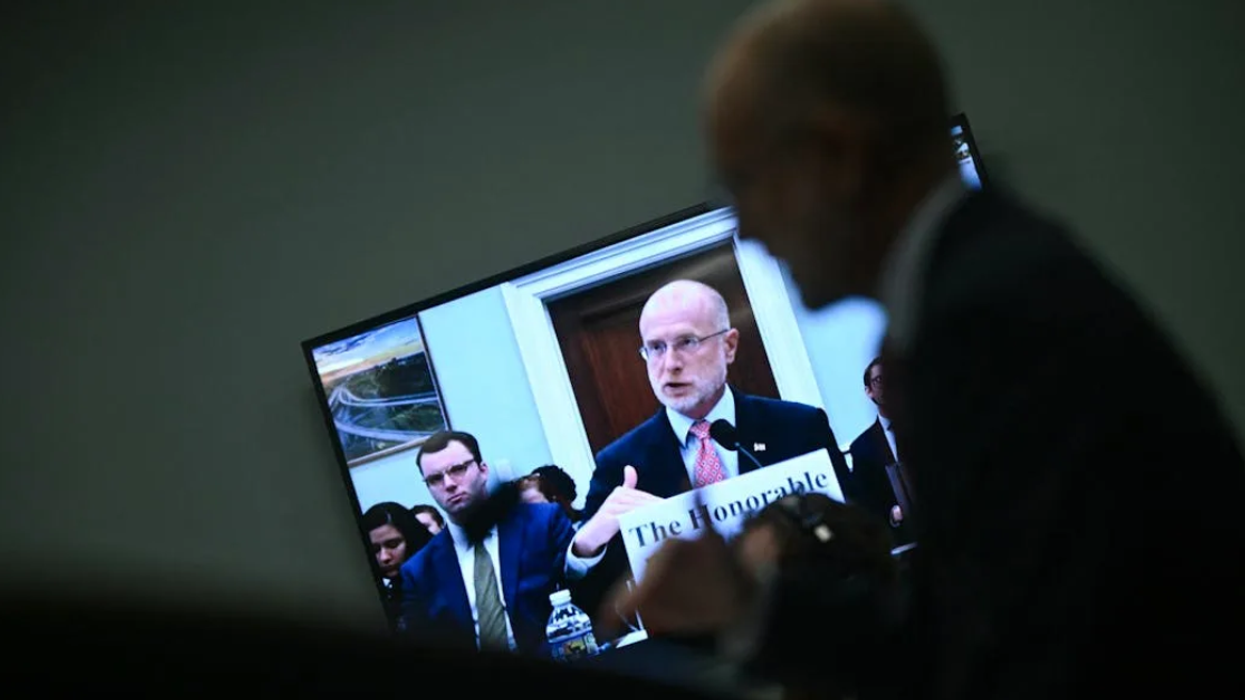

I’m not just referring to the recent controversy between FCC Chairman Brendan Carr, ABC and Jimmy Kimmel. The same chain of events has happened repeatedly in U.S. history.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s FCC chairman, James Lawrence Fly, warned the networks about censoring news commentators.

Then there was John F. Kennedy’s FCC chairman, Newton Minow, who criticized the networks for not airing more news and public affairs programming to support American democracy during the Cold War.

And there was George W. Bush’s FCC chairman, Michael Powell. He decided that a fleeting “wardrobe malfunction” during the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show – when Janet Jackson’s breast was exposed – was sufficient to punish CBS with a fine.

In each of those cases, the FCC represented the views of the White House. And in each case, the regulatory agency was employed to pressure the networks into airing content more aligned with the administration’s ideology.

But what’s interesting in those four examples is that two of the FCC chairmen were Democrats – Fly and Minow – and two were Republicans – Powell and Carr.

As a media historian, I’m aware of the long-existing bipartisan enthusiasm for exploiting the fact that no First Amendment exists in American broadcasting. Pressuring broadcasters by leveraging FCC power occurs regardless of which party controls the White House. And when the agency is used in partisan fashion, the rival party will criticize such politicization of regulation as a threat to free speech.

This recurring cycle is made possible by the fact that broadcasting is licensed by the government. Since a Supreme Court decision in 1943, the supremacy of the FCC in broadcast regulation has been unquestioned.

Such strong governmental oversight separates broadcasting from any other medium of mass communication in the United States. And it’s the reason why there’s no “free speech” when it comes to Kimmel, or any other performer, on U.S. airwaves.

The FCC’s empowerment

Since its establishment in 1934, the FCC’s primary role in broadcasting has been to authorize local station licenses “in the public interest, convenience, or necessity.”

In 1938, the FCC began its first investigation into network practices and policies, which resulted in new regulations. One of the new rules stated that no network could own and operate more than one licensed station in any single market. This forced NBC, which owned two networks that operated stations in several markets, to divest itself of one of its networks. NBC sued.

In the first serious constitutional test of the FCC’s full authority, in 1943, the Supreme Court vindicated the FCC’s expansive power over all U.S. broadcasting in its 5–4 verdict in National Broadcasting Co. v. United States. The ruling has stood since.

That’s why there’s no First Amendment in broadcasting. The Supreme Court ruled that, due to spectrum scarcity – the idea that the airwaves are a limited public resource and therefore not every American can operate a broadcast station – the FCC’s power over broadcasting must be expansive.

The 1934 act, the 1943 Supreme Court decision read, “gave the Commission … expansive powers … and a comprehensive mandate to ‘encourage the larger and more effective use of radio in the public interest,’ if need be, by making ‘special regulations applicable to radio stations engaged in chain (network) broadcasting.’”

The ruling also explains why the FCC can be credited with having created the American Broadcasting Company. Yes, the same ABC that suspended Kimmel in the face of FCC threats was the network that emerged from NBC’s forced divestiture of its Blue Network as a result of the 1943 Supreme Court decision.

The empowerment of the FCC by NBC v. U.S. led to such content restrictions as the Fairness Doctrine, which intended to ensure balanced political broadcasting, instituted in 1949, and later, additional FCC rules against obscenity and indecency on the airwaves. The Supreme Court decision also encouraged FCC chairmen to flex their regulatory muscles in public more often.

For example, when CBS suspended news commentator Cecil Brown in 1943 for truthful but critical news commentary about the U.S. World War II effort, FCC Chairman Fly expressed his displeasure with the network’s decision.

“It is a little strange,” Fly told the press, “that all Americans are to enjoy free speech except radio commentators.”

When FCC Chairman Minow complained about television in the U.S. devolving into a “vast wasteland” in 1961, the networks responded both defensively and productively. They invested far more money into news and public affairs programming. That led to significantly more news reporting and documentary production throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

A ‘hands-off’ FCC

In the early 2000s, FCC Chairman Powell promised to “refashion the FCC into an outfit that is fast, decisive and, above all, hands-off.”

Yet his promise to be “hands-off” did not apply to content regulation. In 2004, his FCC concluded a contentious legal battle with Clear Channel Communications over comments ruled “indecent” by shock jock Howard Stern. The settlement resulted in a US$1.75 million payment by Clear Channel Communications – the largest fine ever collected by the FCC for speech on the airwaves.

Powell apparently enjoyed policing content, as evidenced by the $550,000 fine his FCC levied against CBS for the fleeting exposure of singer Janet Jackson’s breast during the Super Bowl. The fine was eventually overturned. But Powell did successfully lobby Congress to significantly hike the amount of money the FCC could fine broadcasters for indecency. The fine for a single incident increased from $32,000 to $325,000, and up to $3 million if a network broadcasts it on multiple stations.

Powell’s regulatory activism, done mostly to curb the outrageous antics of radio shock jocks, resulted in some of the most significant and long-lasting restrictions on broadcast freedom in U.S. history. Thus, Carr’s 2025 threats toward ABC can be viewed in a historical context as an extension of established FCC activism.

Demonstrators hold signs on Sept. 18, 2025, outside Los Angeles’ El Capitan Entertainment Centre, where the late-night show ‘Jimmy Kimmel Live!’ is staged. AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes

Demonstrators hold signs on Sept. 18, 2025, outside Los Angeles’ El Capitan Entertainment Centre, where the late-night show ‘Jimmy Kimmel Live!’ is staged. AP Photo/Damian DovarganesBut Carr’s threat also appeared to contradict his previously espoused values.

As the author of the FCC section in Project 2025, a conservative blueprint for federal government policies, Carr wrote: “The FCC should promote freedom of speech … and pro-growth reforms that support a diversity of viewpoints.” In exploiting the FCC’s licensing power to threaten to penalize speech he found offensive, Carr failed to promote either freedom of speech or diversity of viewpoints.

If there’s one thing the Carr-Kimmel episode teaches us, it’s that more Americans should know the structural constraints in the U.S. system of broadcasting. Media literacy has proved essential as curbs to free expression – both official and unofficial – have become more popular.

When the FCC threatens a broadcaster, it does so in Americans’ name.

If Americans applaud regulatory activism when it supports their partisan beliefs, consistency demands they accept the same regulatory activism in the hands of their political opponents. If Americans prefer their political opposition show restraint in the regulation of broadcasting, then they need to promote restraint when their preferred administration is in power.

The limits of free speech protections in American broadcasting was first published on The Conversation and republished with permission.

Michael J. Socolow is a Professor of Communication and Journalism at the University of Maine