McDermott is a professor of political science at Fordham University. Jones is a professor of political science at Baruch College, CUNY.

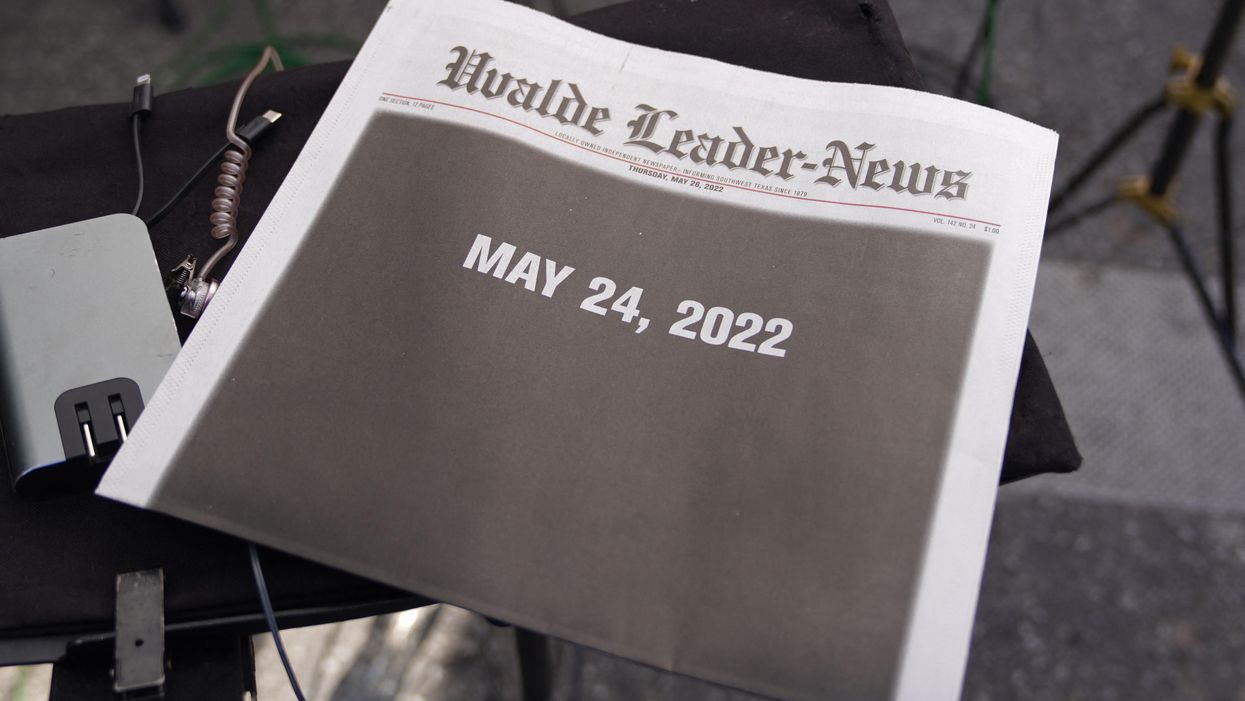

With the carnage in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, N.Y.,in May 2022, calls have begun again for Congress to enact gun control. Since the 2012 massacre of 20 children and four staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., legislation introduced in response to mass killings has consistently failed to pass the Senate. The Conversation asked political scientists Monika McDermott and David Jones to help readers understand why further restrictions never pass, despite a majority of Americans supporting tighter gun control laws.

Mass killings are becoming more frequent. Yet there has been no significant gun legislation passed in response to these and other mass shootings. Why?

McDermott: While there is consistently a majority in favor of restricting gun access a little bit more than the government currently does, usually that’s a slim majority – though that support tends to spike in the short term after events like the recent mass shootings.

We tend to find even gun owners are in support of restrictions like background checks for all gun sales, including at gun shows. So that’s one that everyone gets behind. The other one that gun-owning households get behind is they don’t mind law enforcement taking guns away from people who have been legally judged to be unstable or dangerous. Those are two restrictions on which you can get virtual unanimous support from the American public. But agreement on specific elements isn’t everything.

This isn’t something that people are clamoring for, and there are so many other things in the mix that people are much more concerned about right now, like the economy. Also, people are insecure about the federal budget deficit, and health care is still a perennial problem in this country. So those kinds of things top gun control legislation in terms of priorities for the public.

So you can’t just think about majority support for legislation; you have to think about priorities. People in office care what the priorities are. If someone’s not going to vote them out because of an issue, then they’re not going to do it.

The other issue is that you have just this different view of the gun situation in gun-owning households and non-gun-owning households. Nearly half of the public lives in a household with a gun. And those people tend to be significantly less worried than those in non-gun households that a mass shooting could happen in their community. They’re also unlikely to say that stricter gun laws would reduce the danger of mass shootings.

The people who don’t own guns think the opposite. They think guns are dangerous. They think if we restricted access, then mass shootings would be reduced. So you’ve got this bifurcation in the American public. And that also contributes to why Congress can’t or hasn’t done anything about gun control.

How does public opinion relate to what Congress does or doesn’t do?

Jones: People would, ideally, like to think that members of Congress are responding to public opinion. I think that is their main consideration when they’re making decisions about how to prioritize issues and how to vote on issues.

But we also have to consider: What is the meaning of a member’s “constituency”? We can talk about their geographic constituency – everyone living in their district, if they’re a House member, or in their state, if they’re a senator. But we could also talk about their electoral constituency, and that is all of the people who contributed the votes that put them into office.

And so if a congressmember’s motive is reelection, they want to hold on to the votes of that electoral constituency. It may be more important to them than representing everyone in their district equally.

In 2020, the most recent congressional election, among citizens who voted for a Republican House member, only 24% of those voters wanted to make it more difficult to buy a gun.

So if you’re looking at the opinions of your voters versus those of your entire geographic constituency, it’s your voters that matter most to you. And a party primary constituency may be even narrower and even less in favor of gun control. A member may have to run in a party primary first before they even get to the general election. Now what would be the most generous support for gun control right now in the U.S.? A bit above 60% of Americans. But not every member of Congress has that high a proportion of support for gun control in their district. Local lawmakers are not necessarily focused on national polling numbers.

You could probably get a majority now in the Senate of 50 Democrats plus, say, Susan Collins and some other Republican or two to support some form of gun control. But it wouldn’t pass the Senate. Why isn’t a majority enough to pass? The Senate filibuster – a tradition allowing a small group of Senators to hold up a final vote on a bill unless a three-fifths majority of Senators vote to stop them.

McDermott: This is a very hot political topic these days. But people have to remember, that’s the way our system was designed.

Jones: Protecting rights against the overbearing will of the majority is built into our constitutional system.

Do legislators also worry that sticking their neck out to vote for gun legislation might be for nothing if the Supreme Court is likely to strike down the law?

Jones: The last time gun control passed in Congress was the 1994 assault weapons ban. Many of the legislators who voted for that bill ended up losing their seats in the election that year. Some Republicans who voted for it are on record saying that they were receiving threats of violence. So it’s not trivial, when considering legislation, to be weighing, “Yeah, we can pass this, but was it worth it to me if it gets overturned by the Supreme Court?”

Going back to the 1994 assault weapons ban: How did that manage to pass and how did it avoid a filibuster?

Jones: It got rolled into a larger omnibus bill that was an anti-crime bill. And that managed to garner the support of some Republicans. There are creative ways of rolling together things that one party likes with things that the other party likes. Is that still possible? I’m not sure.

It sounds like what you are saying is that lawmakers are not necessarily driven by higher principle or a sense of humanitarianism, but rather cold, hard numbers and the idea of maintaining or getting power.

McDermott: There are obvious trade-offs there. You can have high principles, but if your high principles serve only to make you a one-term officeholder, what good are you doing for the people who believe in those principles? At some point, you have to have a reality check that says if I can’t get reelected, then I can’t do anything to promote the things I really care about. You have to find a balance.

Wouldn’t that matter more to someone in the House, with a two-year horizon, than to someone in the Senate, with a six-year term?

Jones: Absolutely. If you’re five years out from an election and people are mad at you now, some other issue will come up and you might be able to calm the tempers. But if you’re two years out, that reelection is definitely more of a pressing concern.

Some people are blaming the National Rifle Association for these killings. What do you see as the organization’s role in blocking gun restrictions by Congress?

McDermott: From the public’s side, one of the important things the NRA does is speak directly to voters. The NRA publishes for their members ratings of congressional officeholders based on how much they do or do not support policies the NRA favors. These kinds of things can be used by voters as easy information shortcuts that help them navigate where a candidate stands on the issue when it’s time to vote. This gives them some credibility when they talk to lawmakers.

Jones: The NRA as a lobby is an explanation that’s out there. But I’d caution that it’s a little too simplistic to say interest groups control everything in our society. I think it’s an intermingling of the factors that we’ve been talking about, plus interest groups.

So why does the NRA have power? I would argue: Much of their power is going to the member of Congress and showing them a chart and saying, “Look at the voters in your district. Most of them own guns. Most of them don’t want you to do this.” It’s not that their donations or their threatening looks or phone calls are doing it, it’s the fact that they have the membership and they can do this research and show the legislator what electoral danger they’ll be in if they cast this vote, because of the opinions of that legislator’s core constituents.

Interest groups can help to pump up enthusiasm and make their issue the most important one among members of their group. They’re not necessarily changing overall public support for an issue, but they’re making their most persuasive case to a legislator, given the opinions of crucial voters that live in a district, and that can sometimes tip an already delicate balance.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.