Goldstone’s most recent book is "On Account of Race: The Supreme Court, White Supremacy, and the Ravaging of African American Voting Rights."

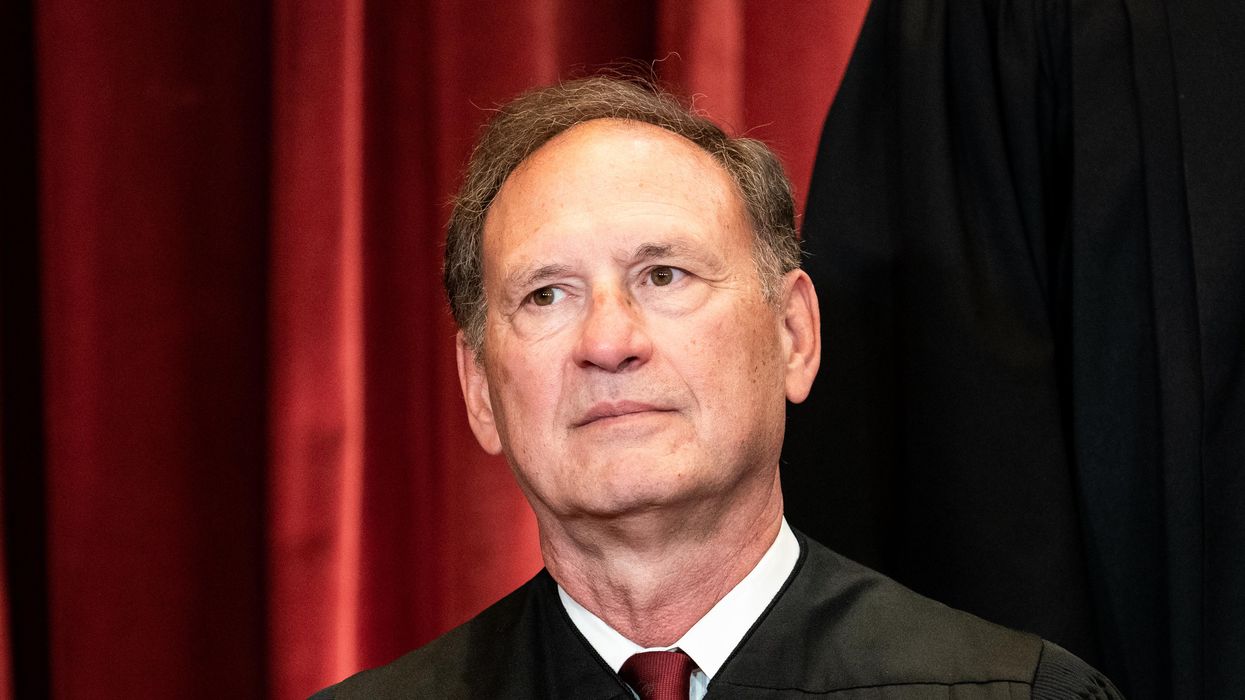

Many Americans, most notably Chief Justice John Roberts, were aghast at the leak of Samuel Alito’s draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Roberts ordered an investigation into the “appalling” breach of etiquette and said he hoped “one bad apple” would not spoil the public’s trust in the Supreme Court, an odd statement to make with the court’s approval rating at an all time low. Justice Clarence Thomas, whose wife was active in the attempt to subvert the 2020 presidential election by bullying Mike Pence into violating his vice presidential oath of office, insisted the court would not be bullied by the public reaction to Alito’s draft.

Thomas was referring, in part, to abortion rights advocates conducting silent vigils outside the homes of some the justices, especially Brett Kavanaugh, who seems loath to be reminded that, under oath, he assured senators that he viewed Roe v. Wade as “settled law.” Deeming peaceful silent protest as more egregious than armed violent protest, many conservative commentators demanded that the leaker be identified and prosecuted, although it seems that leaking the draft was not actually a crime. All the critics agreed that this heinous act threatened the independence of the Supreme Court and was therefore a blow to American democracy.

But the Supreme Court is not so much independent as it is omnipotent. Unelected and appointed for life by virtue of a questionable reading of Article III of the Constitution, the justices are accountable to no one, either in government or among the citizenry. The court has evolved from its intended role — according to Alexander Hamilton — as the “peoples’” branch of government, there to protect the weak against the strong, to a haughty, narcissistic body that protects those with whom it agrees from those with whom it does not.

There can be no more compelling evidence of the perversion of the court’s integrity than Samuel Alito’s draft opinion. Little more than a 98-page diatribe, Alito, seemingly gleefully, attacked a bevy of former justices, many of whom were Republicans, and blithely tossed 50 years of jurisprudence onto the trash pile. Under ordinary circumstances, publication of that opinion would not have taken place until the final decision was announced at the end of the term, after which Alito and his fellow justices would quickly hot-foot it out of town for summer vacation.

As it is, however, Alito has to remain in Washington, where his treatise has not only engendered sharp criticism from many legal scholars who found his reasoning faulty and self-serving, but has also evoked ridicule for citing as an authority an English legal scholar whose views on rape were abhorrent, even for the 17th century. Alito has shown himself to be nothing if not arrogant — he once effectively called President Barack Obama a liar during a State of the Union address — but it is not clear that even he would have written such a shrill, blatantly partisan opinion if he knew it would be subject to general dissemination. But write it he did and, as a result, everyone in the United States knows how fanatical are his views and the lengths he will go to justify them.

All of which puts Alito and his four colleagues in something of a bind. If he softens his opinion for the final draft, he leaves himself open to being charged by his ideological bedfellows with giving in to pressure; if he does not, his screed becomes part of the Court’s permanent record. Those who concurred in the draft opinion are in a similar predicament. If they change their votes or write concurring opinions that are less strident, pro-choice advocates will be convinced that public pressure works. Pro-lifers, their constituency, will feel betrayed. If the justices continue to concur, they are permanently part of a decision that has every possibility of being considered among the court’s worst, right up there with Dred Scott and Korematsu v. United States.

Rather than a strain on democracy, however, forcing justices to face just such a choice is a step forward. Almost a dozen years ago, I wrote in my book “Inherently Unequal,” “Constitutional Law is simply politics made incomprehensible to the common man.” The notion was scoffed at — a reviewer in The Washington Post referred to it as a “sound bite” — but I believe time has proved the assertion accurate. If the people are to have any chance of asserting control over the people’s branch of government, this must change. Americans need to have as much understanding as possible of the workings of that branch, and Supreme Court justices being required to share their thinking is a move in that direction.

Publishing draft opinions is not a panacea, of course. It has been argued that it would have no real impact since justices, aware that their more extreme views will be subject to public scrutiny, will be less likely to put them on paper and instead moderate their drafts to appear less offensive to those who disagree. But that moderation, as false as it may be, will make justices at least consider the impact of their words, which will perhaps, for some if not all, lead to more moderation in their thinking. They will at least be forced to consider contrary points of view, which at present seems sadly absent in their deliberations.

In addition, those opposed to publishing drafts insist that whether groundbreaking decisions are issued during a court’s term or at its end makes no difference. But there is a difference. As it stands, Alito and his compatriots cannot simply walk away from this decision as a fait accompli. They are forced to live with the consequences while the Court is still in session.

The publication of Alito’s draft opinion was, then, a positive development for a society in which the judiciary has run amok. Making it precedent might be a small step forward in rejuvenating a moribund American democracy, which currently operates almost solely in the service of a vocal, uncontrolled minority.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room