A visit to the Anne Frank exhibition led me from history to family memory to the words we hear now.

The Annex and the Weight of Silence

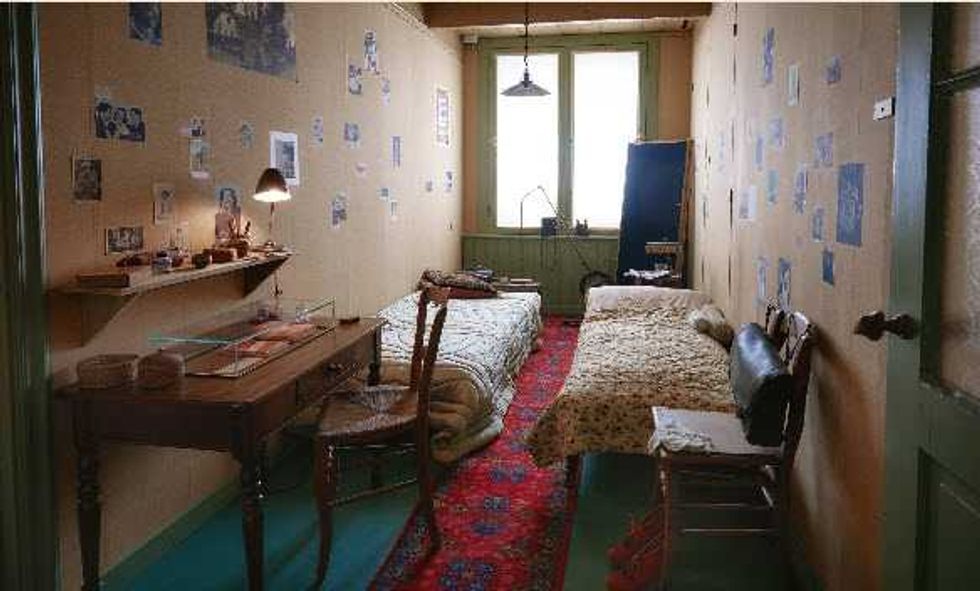

At the Anne Frank exhibition in New York, I stood in the narrow rooms of the Secret Annex at the back of the building where her father had worked and her family was hidden. Thin beds. Curtains drawn tight. A childhood arranged around quiet and fear. Anne and her family hid there beginning in July 1942, after her sister Margot was ordered to report for deportation under the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. By then, Jews had been stripped of rights, barred from schools and public places, forced to wear the yellow star, and were being rounded up for transport to labor and extermination camps.

For more than two years, they lived there in constant danger, forced to walk softly, speak in whispers, and flush the toilet only at certain hours, their survival dependent on the protection of a few sympathetic non-Jews. Even the slightest noise at the wrong time could mean discovery.

Childhood in the Annex was measured in silence. Games, laughter, even footsteps had to be suppressed, for every sound carried danger. Life narrowed to waiting, and each day stretched under the weight of fear that discovery could come at any moment, ending their fragile safety.

The rooms were ordinary in their furnishings, yet they spoke of a world where ordinary life had been steadily closed off. That narrowing did not begin with violence. It began with language—words that marked Jews as outsiders, parasites, and threats to the nation. Those words spread until they felt ordinary, and once ordinary, they hardened quickly into laws, arrests, and violence.

On the audio tour, a line from Anne’s diary stopped me: “One day this terrible war will be over. The time will come when we’ll be people again and not just Jews!”

AA Full-Scale Recreation of Anne Frank’s hiding placeCredit: Anne Frank: The Exhibition

AA Full-Scale Recreation of Anne Frank’s hiding placeCredit: Anne Frank: The Exhibition

Echoes in My Family’s America

Her words took me back to my own family. My parents were born in the early 1920s in the United States, the children of Polish immigrants. They told me stories of their growing up in America. As children, they learned which neighborhoods did not rent to Jews. As teenagers, they knew which school dances and clubs would not admit them. As young adults, even after the war, they tried taking a vacation in the Berkshires and were turned away at a resort that openly excluded Jews.

My mother would sum it up with quiet resignation: “We knew where we weren’t wanted.”

My life in America was different. I did not face overt antisemitism. At times, it was so subtle I could never be sure—like being turned down as a roommate in graduate school and left wondering if my being Jewish was the reason.

Language, Targets, and Fragile Hope

I listen now to how those in power describe people: immigrants painted as “poisoning the blood of our country”, opponents reduced to “vermin”. We have heard this before. In Germany, Jews were cast as outsiders, and words quickly turned into action.

Today, the primary target is immigrants, often portrayed as “illegal” and especially Latin American. Hostility has also been directed at Jews, Muslims, and other marginalized groups. For Black Americans, the experience has been both blatant and subtle for centuries.

Anne Frank hoped for a day when people would be seen not as labels but as people first. Her hope remains fragile, as fragile as the line between belonging and exclusion, a line that words can erase in an instant.

Edward Saltzberg is the Executive Director of the Security and Sustainability Forum and writes The Stability Brief.