Hornbeck is a postdoctoral research fellow of educational leadership and policy at the University of Texas at Arlington.

When the U.S. Supreme Court issued its 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision that struck down segregated public schooling, white Southern politicians responded to the decision with ferocity.

Although preservation of states' rights was at the heart of their resistance claims, it was the racist practice of segregation that they sought to uphold.

Sen. Harry Byrd of Virginia declared the ruling "the most serious blow that has yet been struck against the rights of the states." Thomas P. Brady, Mississippi circuit judge and future state Supreme Court justice, called the day of the ruling "Black Monday." Brady also claimed that racial integration was a communist plot to unify the country around one common culture.

Over 100 Southern House and Senate members signed a Southern Manifesto, vowing to stop school integration in what Byrd called a "massive resistance." The governor of Virginia, Thomas Manley, appointed a commission to explore legal options in the wake of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision. The Gray Commission, as it was known, recommended that no child in Virginia "be required to attend a school wherein both white and colored children are taught."

I don't bring up this Southern resistance to federal mandates that affect U.S. schools merely to recount history. As a researcher who focuses on the role of federalism in U.S. education, I believe this resistance helps shine light on why several Southern states today are pushing back against federal guidance for teachers and students to wear masks in schools to lessen the risks of contracting the more dangerous delta variant of Covid-19.

Defiance in spite of risks

In late July 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and President Biden recommended students wear masks in schools to protect themselves and others from Covid-19.

Subsequently, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis issued an executive order that banned schools in the state from requiring masks, claiming that the masks are unproven to be effective and might cause harm to children. The governors of Texas and Arizona took similar measures, leaving schools, concerned parents, teachers and vulnerable students few options and with little time before the school year began to decide how to respond. The Texas legislature is considering legislation that would make public mask requirements illegal.

A history of resistance

Southern states ignoring federal educational guidance is not new.

For instance, rather than integrate schools, Virginia elected to close many school districts and instead offer white students vouchers to attend private schools. The state legislature enabled this in 1956, when it passed laws that stripped local school boards of their power and put it in the hands of committees appointed by the governor.

When Lindsey Almond took over as governor of Virginia in 1957, he warned that integrated schools would lead to the "livid stench of sadism, sex, immorality, and juvenile pregnancy" that he claimed existed in nearby Washington's integrated school system.

Other acts of resistance

In Mississippi, things were little different than in Virginia. Gov. Hugh White thought that he might avoid integration by convincing Black residents to voluntarily agree to continue segregation. He promised more money for schools. He met with 90 Black leaders and asked for voluntary segregation. The plan failed when only one person at the meeting agreed to the proposal. As a result, the governor called a special session of the state legislature.

The legislature passed a bill that led to the closure of public schools in the state. Public schools would be mostly private and segregated. It took 16 years for Mississippi schools to comply with the Brown decision and fully integrate.

Other states resisted integration in similar ways, with various policies that privatized public schools, leading to the modern civil rights movement. The civil rights movement opened the door for a larger federal government role in educational policy. The Justice Department has the authority to investigate and prosecute schools under the Title IX provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that mandates civil rights protection for students.

Fight against federal government continues

Fast forward to 2021 and governors and lawmakers in states such as Florida, Texas and Arizona are clamoring with a similar states' rights argument as their predecessors.

Like Virginia and Mississippi in the 1950s, these states are attempting to undermine federal intervention in schools. The U.S. Constitution creates a federal system where the national government shares power with states. Any power not explicitly listed in the Constitution is left to the states, per the 10th Amendment. As a result, educational policy is largely left to the states, so long as civil rights are protected.

Within states, power is shared with local governments in whatever way state constitutions and law decide. DeSantis has threatened retaliation against schools who defy his order by cutting superintendent salaries. Yet, a state judge stopped his order. DeSantis claims that he will win on appeal.

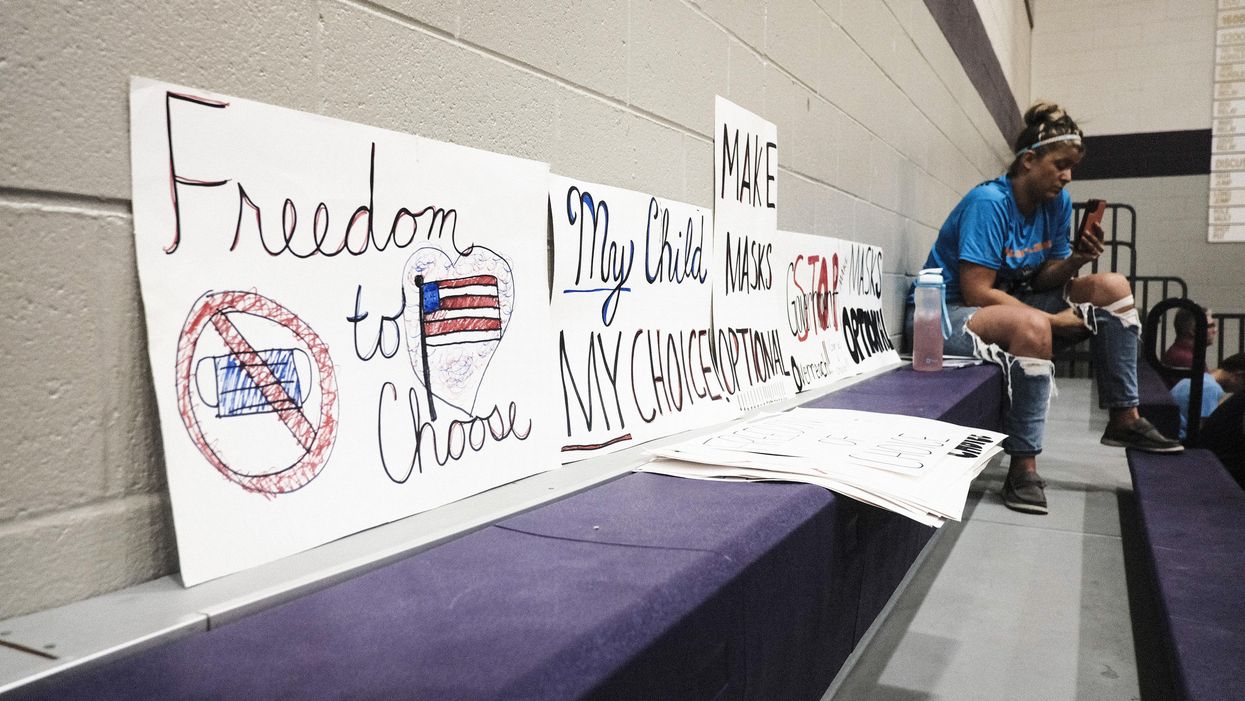

Texas and Arizona officials have threatened consequences, such as loss of funding and lawsuits, to school districts that mandate masks. Threatening localities with retaliation did not prevent the eventual integration of schools in the South. Considering that local school districts are following federal health guidance, threats from governors to browbeat localities into submission have stirred community outrage from parents and lawsuits from concerned citizens.

Nevertheless, federalism makes power-sharing between the states and federal government complicated. The Constitution gives states the power to create their own educational and health policies, but the federal government can enforce civil rights laws in schools, making educational policy political whether people like it or not.

This is why, on Aug. 30, 2021, the U.S. Department of Education announced that it would investigate whether statewide mask bans deny civil rights to students with disabilities.

Like school integration in the past, policies that require or encourage masks have become the new arena for the ongoing American argument about Southern states' rights.

![]()

Will Trump’s moves ever awaken conservatives?