Friedrich is vice provost and a professor of sociolinguistics at Arizona State University.

In their campaigns, former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris project different emotions and moods. The contrast between them was particularly sharp during their debate on Sept. 10, 2024.

One candidate made appeals to the past, used more negative words and invoked fear. The other spoke more of the future, used more positive words and appealed to voters’ sense of hope.

As a linguist, writer and professor who teaches mostly sociolinguistics – how language operates in society – I have always been fascinated by the ways in which people tend to use language in patterns. The recent Harris-Trump debate offered me an opportunity to examine how these candidates were using language to win over voters.

Looking at which approach a candidate chooses can reveal deeper truths about them. Traditionally, according to the study of rhetoric and language, politicians can appeal to reason, emotion or authority – or some combination of them – to persuade their audiences. In terms of emotion, both fear and hope can be effective at motivating voters. There’s not a right or wrong way to do it.

Linguists have developed the concept of the idiolect, an individual dialect that is like a fingerprint, different for each individual, and made out of our unique linguistic and social experiences.

People often prepare and rehearse for public speaking events. But once they are actually facing an audience, they tend to revert to what is intuitive and already second nature to them – their idiolect. A speaker is not thinking about how long their sentences are, for example. They are thinking about the ideas they want to express. They might not realize that there are patterns to their speech and delivery, or that they return to the same words again and again.

Negativity

I prompted an artificial intelligence tool to answer questions about frequency of words, lengths of sentences and kinds of words in the debate. I checked all of the output of the AI tool manually, so I could make sure there were no discrepancies.

Here’s what I was looking for: I anticipated that the candidates’ use of language in the debate would reflect their differing approaches to campaigning, particularly in terms of past or present orientation, appeals to fear or hope, and negative or positive statements.

I found that it did.

First, I selected six segments of the debate transcript, each of equivalent lengths and each featuring both candidates responding to the same question, or at least a similar one.

Then I looked at negativity in their language. I expected that more negative statements would more closely align with appeals to the politics of fear, while more positive ones would relate more closely to the politics of hope. If a candidate is appealing to fear, they will likely focus on things that may or have gone wrong. By contrast, if they focus on hope, they are likely to focus on what might go right in the future.

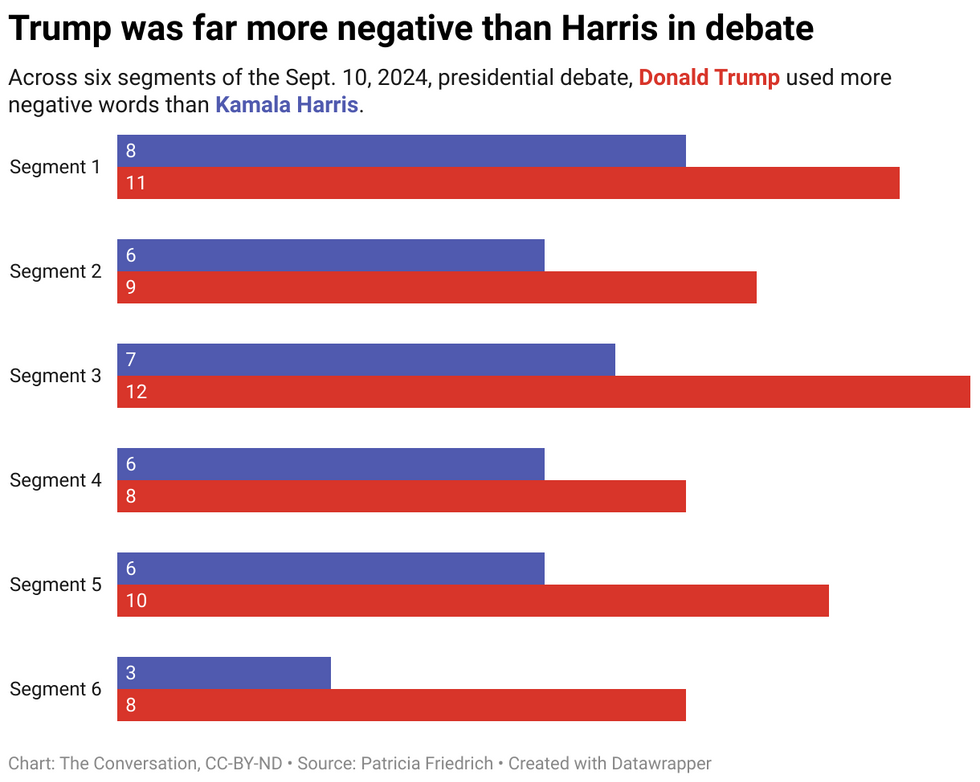

I found that Trump consistently made more negative statements than Harris. That was true of each of the six segments individually, with rates varying from 33% more to 166% more.

For example, in a 30-second segment, Trump used negative statements and words such as “totally destroy” and “disaster” 12 times. In her 30-second response, Harris used negative statements or words only seven times.

The tenor of the terms was also different: Trump’s negative words tended to be stronger, such as “violently,” “very horribly” and “ridiculous.” Overall, for all the segments I analyzed, Trump made, on average, about 61% more negative statements than Harris.

Shorter sentences

Then I looked at sentence length. I thought shorter sentences might tend to communicate a sense of urgency that would align more closely with fear, and that longer ones could be more fluid and calmer, and therefore more associated with hope. I looked at three segments from the original set of six.

Intuitively, people might think that short statements are a reflection of directness and addressing issues head-on, but that is not necessarily the case. For example, one of Trump’s relatively short statements, “The agreement said you have to do this, this, this, this, this, and they didn’t do it,” can be considered evasive because it does not contain the level of specificity that would allow a listener to make their own assessment of whether something has been accomplished or not. And yet, it is simple and short, made a bit longer only by the repetition of “this.”

For the first segment I analyzed, the average length of sentences for Trump was 13 words, while for Harris it was 17 words. The gap widened for the second segment, in which the average length of sentences for Trump was 14 words, while for Harris it was 25 words. That pattern was the same in the third segment as well.

Talk of the future

Finally, I looked at how they talked about the future and the past, and whether they talked about one or the other more, as possible indicators of greater reliance on fear and on hope.

Usually, in the context of fear, the recent past is used as a time to escape from, while the more distant past is a time to return to. By contrast, people who focus on hope look to the future.

The candidates make their closing arguments in the, debate.youtu.be

When I analyzed their concluding remarks, I found that both candidates made the same number of references to the past, but in very different ways. Most of Harris’ references to the past were about the fact that Trump often focuses on it. For example, she said there is “an attempt to take us backward” and continued, “We’re not going back.”

Trump, on the other hand, spoke more about the perceived failures of his opponents in the past, such as, “They’ve had 3½ to fix the border.” He also talked about what he perceives to be his past achievements, such as, “I rebuilt our entire military.”

In terms of future statements, all four of Trump’s were about what he says will happen if his opponent wins – for example, “If she won the election, fracking in Pennsylvania will end on Day 1.”

Harris had nine “future” statements, all of which were about what she intends to do. For example, she said, “And when I am president, we will do that for all people, understanding that the value I bring to this is that access to health care should be a right and not just a privilege of those who can afford it.”

Also in her closing statement, Harris summed up both the debate and the findings of my research:

“You’ve heard tonight two very different visions for our country. One that is focused on the future and the other that is focused on the past. And an attempt to take us backward. But we’re not going back.”

The election outcome will tell whether the American voter at this point in time is drawn more to fear or to hope. The next few weeks will certainly provide large amounts of data for linguistic analyses.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

From left to right: Gabriel Cardona-Fox, Bud Branch, Joe Concienne

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift