Weiss is a consultant to a commercial printer and a member of the local Democratic Committee in suburban Philadelphia's Montgomery County.

The coronavirus has changed just about everything in our day-to-day lives. How we vote is no exception. Mail-in voting will be used by more voters than ever. But where I live — in the most populous suburban county of one of the country's biggest presidential battlegrounds — the procedures are being kept secret for getting absentee ballots sent to voters, then securing and counting them when they're returned.

No-excuse mail-in voting is new to Pennsylvania this year and is being implemented on a county-by-county basis. But there appears to be little oversight or direction from the state elections office in Harrisburg regarding how each county is to implement the new law, provide for cyber-security and physical security, or validate electors and count ballots.

Between February and last week, elected state and county officials, and the Montgomery Board of Elections, were not responsive when asked about plans and procedures for handling the expected surge in mail-in ballots. Prior to the primary in June, the county cited the emergency conditions of the pandemic in saying it was not able to answer the public's right-to-know requests. After that, the county started postponing its promised answers, 30 days at a time. Even some basic information guaranteed by the state's election laws was not provided for the primary, despite five requests by certified mail to the Elections Board chairman, Ken Lawrence.

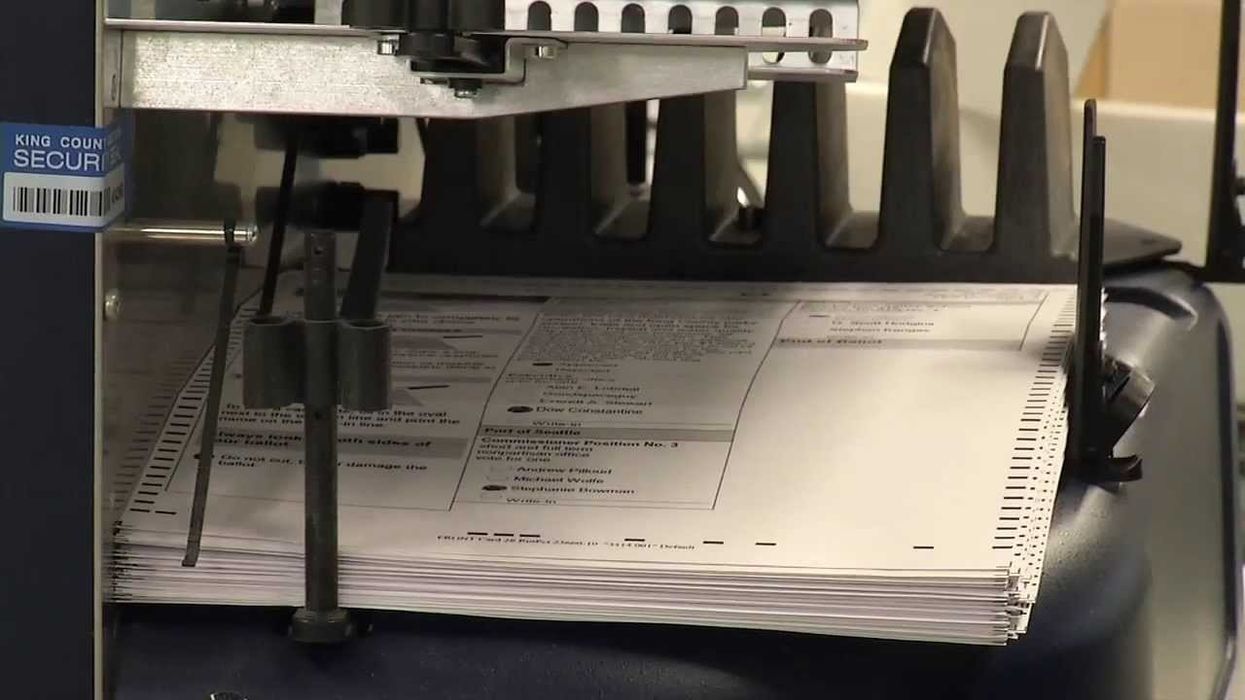

For a stark contrast, look to Seattle. While people answering the phone at the Montgomery County Voter Services office were referring all questions about mail-in ballots to an online open records request form, the similar office in King County offers a video tour of its counting facility — and, when telephoned, provided helpful information about equipment and staffing levels. Colorado, which like Washington has conducted all elections by mail for years, provides a trove of information on government websites.

The lack of such transparency in Pennsylvania is alarming for many reasons. The following questions and more go unanswered:

- What are the standards to approve an application for a mail-in ballot?

- Who is handling the ballots? Are private mail shops being used to send ballots to voters? If so, what steps have been taken to prevent political interference in the process?

- Are there any tracking procedures being used in conjunction with services available from the Postal Service?

- How is material handling being done? Is the storage space secure? What happens if stored ballots get damaged before they're counted — if the roof leaks, for instance?

- How are voter signatures being verified when ballots are returned? How are county employees trained to do this? Is software being used? What happens if there is a problem?

- What happens when ballots are damaged by tabulating equipment? (We have all watched sheets of paper being "eaten" by a document feeder on a copier.)

- What information will be given to poll watchers to help them ensure all ballots are counted, but only counted once?

Based on my experience working with commercial printers and their full-service mail shops, an error rate between 1 percent and 2 percent would not be unreasonable for the first-time processing of a job similar to the size and complexity of the job Montgomery County is facing in November. (Just 4 percent of the 447,000 votes cast in the county in the last presidential contest were absentee; this time the share could easily top 50 percent.)

Smaller counties will likely have a lower error rate, because fewer ballots requires fewer formal procedures for an acceptable result. But in a competitive election, the error rate could still be far greater than the margin of victory.

Montgomery made many mistakes during the primary. Many ballots were not sent, as state law requires, within 48 hours of an application's receipt. The secretary of state's office found that 9.6 percent of those applications were rejected, the highest share among the state's 67 counties, while another 5 percent of county voters confronted other problems — including receiving ballots for the wrong party or wrong precinct.

Finally, there were no obvious quality checks in place for the processing of mailed ballots and virtually no training provided to the election workers responsible for processing the votes.

Had county officials been more transparent from the start, many of these problems could have been headed off.

Certainly, Pennsylvanians do not wish to be debating after the election the rules for counting ballots in what looks to be another super-close presidential race. (President Trump carried our 20 electoral votes by just seven-tenths of 1 point last time.)

County election boards and elected representatives should be providing detailed information now for public review about how ballots will be protected and processed. Anything short of complete transparency calls into question the mail-in vote — and whether voters using this process risk being disenfranchised by inadequate quality assurance procedures, shoddy vendors or poor worker training.

Last week, Montgomery County's chief operating officer, Lee Soltysiak, sought to provide assurances during an hour-long call. The election office has been reorganized into two divisions, one to handle voting on Nov. 3 and one to process mailed ballots. New equipment is being installed and space has been rented for ballot counting and storage. Standard operating procedures are being developed along with worker training for processing ballots. Enhanced security measures are to be implemented. A new vendor has been selected to send out the ballots.

And a public information campaign will be launched soon — although voters haven't been told this raft of heartening news yet.

Citizens who want fair elections cannot simply expect them to happen. They need to press their local governments for complete election transparency — and assurances about when to expect results will be reported.

Only making election transparency an important issue today will ensure fair and uncontested election results in seven weeks, regardless of the complications from Covid-19.