Kendrick is executive director of the Cory Glenville Community Center. He has worked with the Greater Hilltop Area Shalom Zone in Columbus serving people in poverty and engaging in advocacy through direct action such as food distribution, low-income housing and job training.

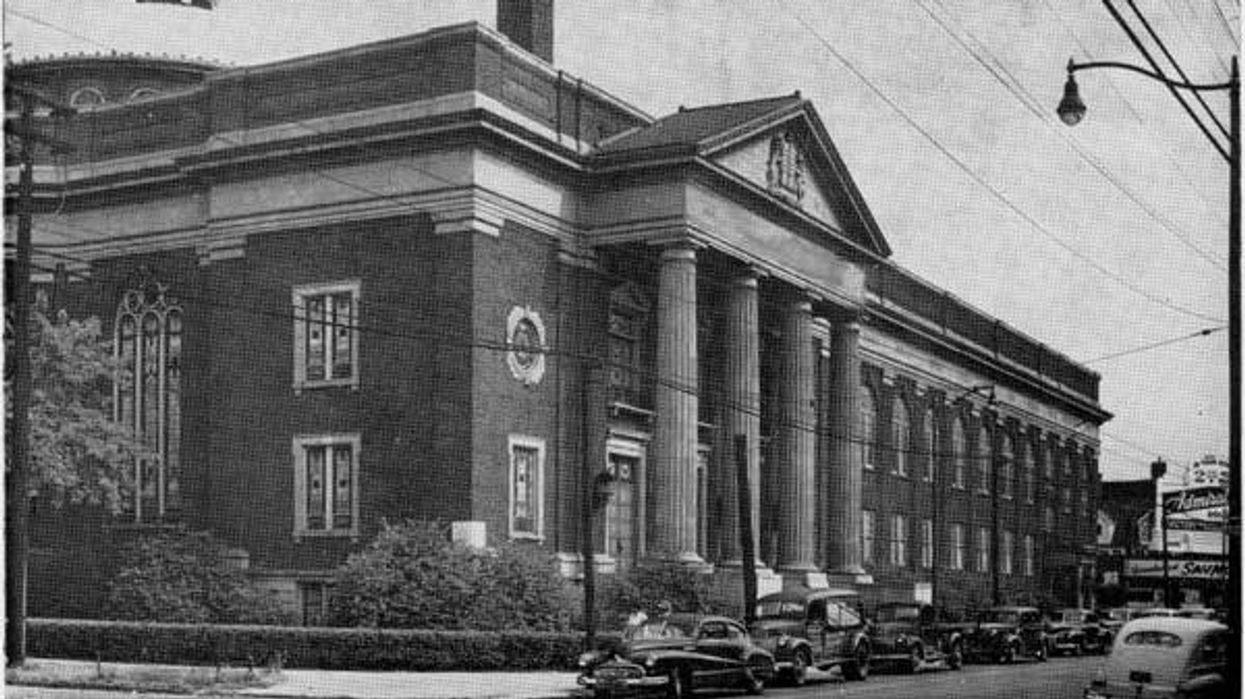

As the pastor of the historic Cory United Methodist Church in the Glenview neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio, I have seen firsthand the immense value of physical spaces. Our church has been a beacon of hope, a sanctuary for activists and a platform for advocacy during the civil rights movement of the 20th century. The walls of Cory UMC have borne witness to the enthusiasm of passionate leaders and the birth of transformative ideas. In a society increasingly engrossed in digital realities, we must remember the significance of the tangible.

Our focus may have shifted towards developing sophisticated virtual platforms and augmented realities. Still, we must pay attention to physical surroundings – the spaces that foster human connection, house our history and serve our communities. We must recognize the power of place-making and the importance of civic engagement in shaping these spaces.

There is an urgent need to preserve places that foster opportunities for human interaction, self-sufficiency and a healthy community. Historic preservation, however, extends beyond merely saving old buildings, although that in itself is crucial. It is about preserving the stories within these structures, the narratives of our past that shape our present and future.

Historic preservation is at the heart of environmental justice, racial equity and human flourishing. Post-industrial cities are nursing the wounds of disinvestment and historical redlining; we must view these old edifices not as relics of a bygone era but as vessels of potential and abundance.

These places matter because they give life to our stories. "There are stories in these bricks," I thought as I observed our front steps' careful, selective demolition. Each brick, fired in giant kilns by the companies that built our cities, is a testament to the industry and ingenuity of our forebears. Each tells the story of the brick masons whose skilled hands shaped our streets and created our physical world.

These bricks bear the echoes of the congregations that gathered within their walls, the communities that envisioned places where people could debate ideas freely, share dreams and build a future for generations. They are living testaments to the adaptive reuse of our architectural heritage, a key to preservation-based economic development.

Places matter. Stories matter. They are the physical embodiment of our collective history, the tangible anchor to our shared past. They remind us of our journey, the struggles faced, the victories won, the dreams realized. They are the silent witnesses to our evolution as a society, our growth as a community and our potential as a people.

Over the years, my involvement with the Bridge Alliance's leadership initiatives has significantly deepened my understanding of the importance of place and story-sharing. The programs are a tapestry of diverse experiences, ideas and perspectives, exposing me to unique narratives from various communities across the nation. Engaging in meaningful dialogues, sharing experiences and brainstorming solutions to common issues, I've been privileged to witness the power of shared stories in shaping our understanding of place.

Like the bricks of Cory, our stories and experiences highlight a particular place's unique challenges and opportunities, further emphasizing the significance of preserving these physical spaces —the Bridge Alliance's learning exchange helps us discern that every place has a uniqueness to celebrate. Stories build bridges between communities, foster unity and promote understanding. They are reinforcing belief in the power of places and the stories they hold.

As a spiritual and civic leader, I'm committed to preserving and transforming our historic spaces and championing the cause of placemaking and civic engagement. Let us remember the value of our physical world in the age of virtual realities. Remember that in our quest for technological advancement, we must stay in the bricks and mortar that ground us in our shared history and humanity. Because places matter, so do the stories and people that result from them, making the community a reality.

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)