Simson is Macon Chair in Law and former dean at Mercer Law School, professor emeritus at Cornell Law School, and a member of the board of directors of Lawyers Defending American Democracy.

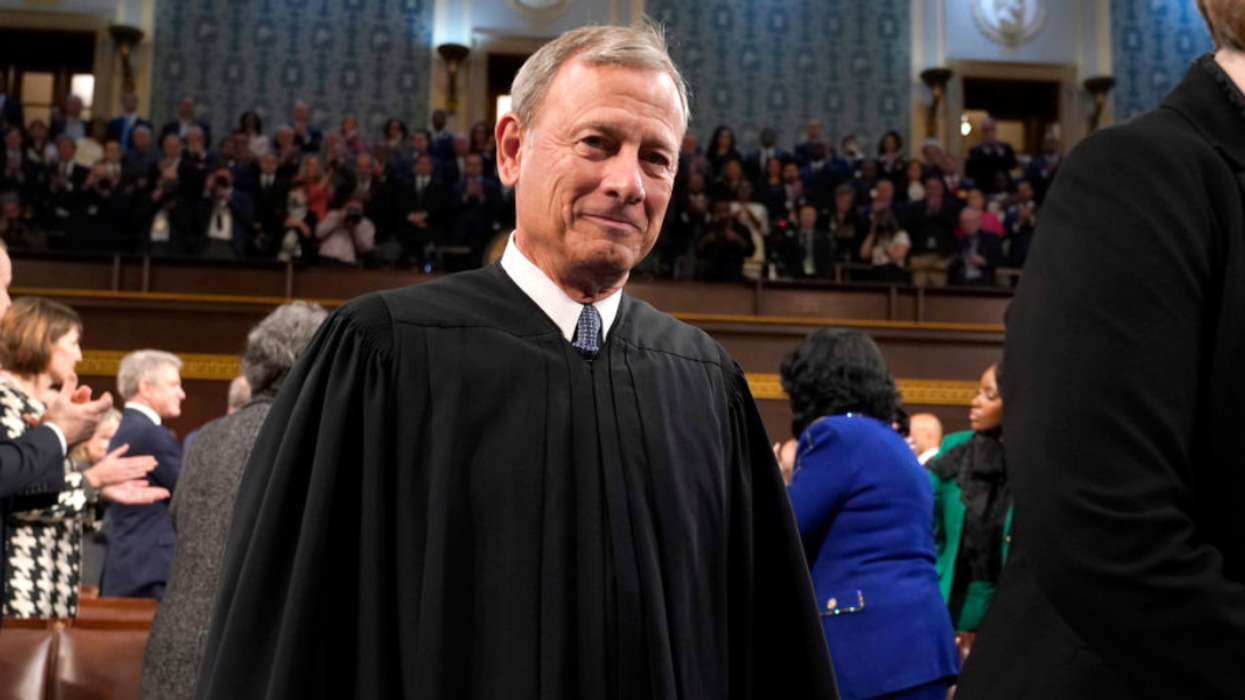

You don’t have to be a big fan of Chief Justice John Roberts to concede that he wouldn’t dream of jet-setting around the country at a conservative billionaire’s expense or hanging outside his home a favorite flag of 2020 election deniers or Christian nationalists. But then why, you must be wondering, was he so unwilling to even meet with the Senate Judiciary Committee when invited in April 2023 to discuss Justice Clarence Thomas’ seemingly conscience-free jet-setting and when invited last month to discuss Justice Samuel Alito’s perhaps even more ethically challenged flag-hanging?

One thing’s for sure: You won’t find the answer in either of the letters the chief justice wrote declining the committee’s invitations. Of course, he wasn’t so impolite as to give no reasons, but the reasons he gave were all stated in such a cryptic or conclusory way that they seemed designed mainly to send the message, “I’m not coming, and I don’t even have to convince you I’m right not to come.”

In both letters he broadly alluded to “separation of powers concerns and the importance of preserving judicial independence.” Separation of powers and judicial independence undoubtedly are principles fundamental to our Constitution, but neither was genuinely threatened by the chief justice meeting with the committee. Both principles have never been understood as absolutes. If they don’t leave room for Congress to question a chief justice when justices act in ways that cast doubt on the Supreme Court’s ability to render impartial justice, our entire system of government is in big trouble.

In one letter, Roberts called attention to “the practice we have followed for 235 years pursuant to which individual Justices decide recusal issues.” Very simply, he seemed to be saying, the Supreme Court since its inception has left it to each justice to decide whether he or she needs to recuse; therefore, it’s illogical to ask a chief justice to discuss another justice’s recusal decisions.

But the longevity and wisdom of a practice are two very different things. Even if we assume that giving individual justices complete autonomy over their own recusal decisions made sense 235 or even 35 years ago, that hardly establishes that it makes sense today, particularly in the teeth of the powerful evidence to the contrary supplied by Thomas’s and Alito’s decisions.

Surely that distinction wasn’t lost on Roberts. I strongly suspect, though, that he was willing to bite the bullet and live with Thomas’s and Alito’s ethically impoverished decisions because he believes that in general anyone not on the Supreme Court, including the many senators on the Judiciary Committee who are lawyers, can’t understand as well as a justice what’s at stake in justices’ recusal decisions.

Roberts undoubtedly recognized that Thomas’ and Alito’s recusal decisions can leave a lot to be desired. He must have been thinking, though, that in the long run the American legal system is best served by the Supreme Court keeping recusal decisions entirely in-house and rejecting any efforts, however well-meaning, of the other branches to review them.

That understanding of the chief justice’s thinking fits neatly with the message sent by the toothless Code of Conduct that the Supreme Court, after much prodding, finally released last fall. It’s also of a piece with the various majority opinions that the chief justice has authored or joined that reject agencies’ interpretations of the federal statutes they are charged with administering. Time and again, those opinions implicitly suggest that the justices are so intellectually gifted that they need not give any particular deference to agencies’ special subject-matter expertise.

Of course, I can’t say for certain that my rendition of the chief justice’s thinking captures what he was actually thinking. I have little doubt, though, that it captures well the message that his refusal actually sent, and it was a message of extraordinary hubris.

There’s simply no basis for his apparent assumption that justices’ recusal decisions are somehow beyond the ken of anyone not sitting on the court. Yes, Supreme Court recusals are unique in some ways. Most importantly, if a justice recuses, no other judge can be designated to sit in their place. To imply, however, as Roberts’ refusal to meet with the Judiciary Committee seemed to do, that senators are somehow incapable of factoring that difference into their thinking when assessing Thomas’ and Alito’s recusal decisions is insulting and wrong.

Public confidence in the Supreme Court is a precious commodity much in need of restoration. Rather than squandering it further by demonstrations of hubris, Roberts should exercise his leadership in ways that model for the other justices and communicate to the public a healthy sense of humility.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift