This was a long day coming, and frankly one I never thought I’d see.

Thirteen years ago, Syria’s Bashar Assad unleashed a reign of unmitigated terror on his own people, in response to protests of his inhumane Ba’athist government.

Over the course of the civil war, he unabashedly committed the worst atrocities imaginable — barrel bombing schools and hospitals, torturing children and the elderly, releasing sarin gas on toddlers and infants. His war on his own people is estimated to have killed 500,000 Syrians, 50,000 of them children. Upwards of 35,000 have been “disappeared” or imprisoned. Millions more have been displaced.

For 13 years, a small cohort of journalists, war reporters, aid groups, and lawmakers tried everything we could to not let these atrocities go unnoticed or forgotten. But it often felt like screaming into a void of indifference.

That indifference is the world’s burden to share, and will always be a tragedy on top of a tragedy — inexplicable, indefensible, unforgivable.

But now that Assad the Butcher is finally gone, we owe it to the Syrian people to correct our moral failures.

The unexpected fall of Assad has brought Syrians hope for the first time in more than 50 years, but it also opens the door to some potentially dangerous unknowns that must be addressed by world leaders. There are two immediate concerns: Assad’s chemical weapons and the state’s Captagon production.

Assad used chemical weapons, including sarin and chlorine barrel bombs, against his own people on multiple occasions. The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) has spent more than 10 years trying to determine exactly which ones the regime still possesses, with no luck. Now is the time to find them and hold Assad accountable for their use, and more importantly, dispose of them properly so they don’t end up in the hands of terrorist factions circling Syria.

Similarly, Captagon is a dangerous synthetic stimulant that’s been mass-produced and trafficked in Syria by the Assad regime since the war began and Syria’s economy imploded. The drug brought in billions for Assad. But Syria cannot rebuild as a narco-state, and containing Captagon is a national security and public safety must.

Then, Syria will need, well, everything — the rebuilding of schools, roads, and hospitals; a functioning government; the means by which to welcome back millions of refugees; protection from vulture groups looking to exploit the new vacuum.

We not only have a role to play in all of this; it’s in our own economic and national security interests to ensure Syria’s rebirth as a democratic partner in the region. And we have the leverage to do it.

In April 2011, the U.S. issued its first sanctions against Syria and many more followed. Eventually, the U.S. would prohibit any new investment in Syria, embargo its oil, impose travel bans, freeze the assets of a number of Syrian entities and persons, and prohibit the export of any U.S. goods and services. The European Union, Australia, the Arab League, Turkey, as well as multiple non-EU countries would follow suit, plunging Syria into economic darkness.

Along with our allies, we should engage in talks to lift these sanctions, and in fact pour resources back into Syria under a checklist of conditions. Syria must draft a new constitution. It must conduct democratic elections. It must release all prisoners of war. It must allow refugees to return home. It must allow outside agents to dispose of its chemical weapons and Captagon.

There is so much more that a new Syria will have to do to regain its stability and economic footholds, to rebuild its infrastructure, to heal its people. It has a long road ahead, after suffering down a long road of Assad’s terror.

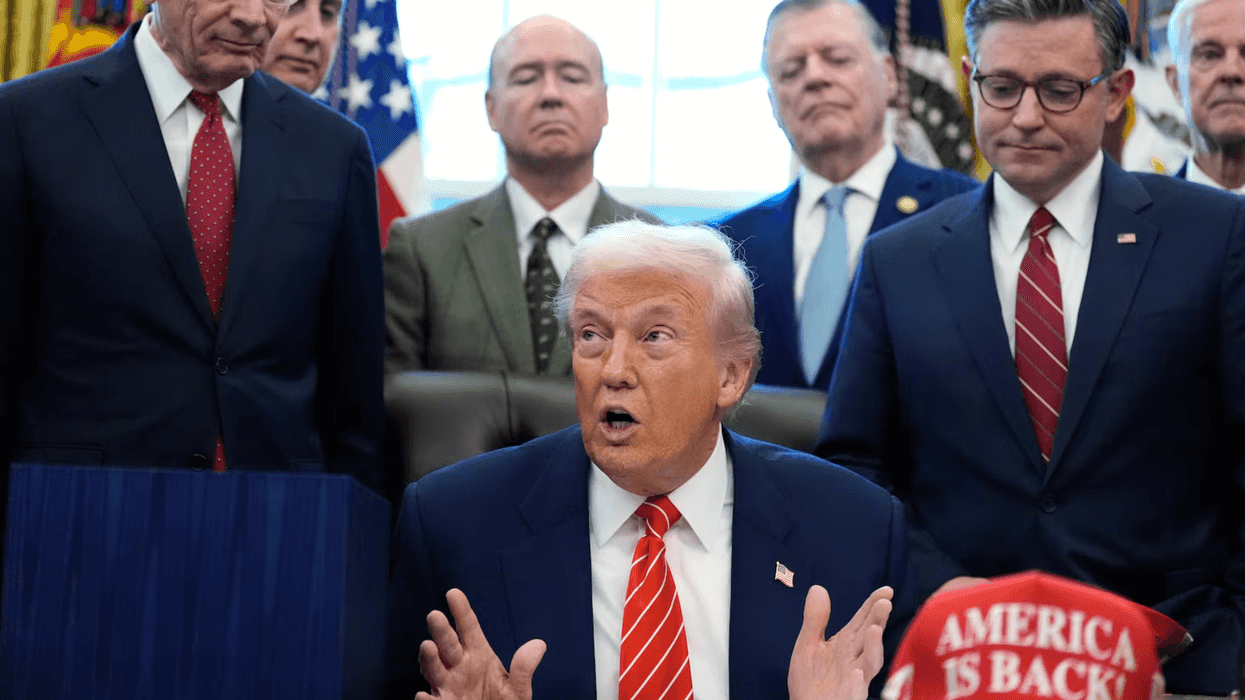

We don’t need to send troops, nor do we need to envision our role as nation builders. This isn’t a heavy lift for the U.S., nor will it put incoming President Trump in a politically compromising or “interventionist” position. We have a golden opportunity to help give the Syrian people what they’ve long been demanding and deserve — a free and fair democracy. That’s good for Syria, and good for America and our allies.

We can’t go back and intervene when perhaps we should have. We can’t bring half a million innocent people back to life. We can’t undo the torture and horrors Bashar Assad brazenly unleashed on his people for years. And we can’t wash the stain of indifference off of our hands.

But we can help Syria rebuild. And after years of inaction and apathy, it’s quite simply the least we can do.

Cupp is the host of "S.E. Cupp Unfiltered" on CNN.

©2024 S.E. Cupp. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room