On a chilly Saturday morning at a Maryland public high school, where one in four students is of Hispanic origin, about twenty-five Latino students and parents gather to hear attorney José Campos explain what to do if U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents show up at their home. “Regardless of your status, you have constitutional rights,” Campos says.

After showing the group what an official judicial warrant looks like, the lawyer urges them to memorize “five magic phrases.” The slide he pulls up reads: “I do not want to talk with you; I do not want you to come inside; Leave; I do not want you to search anything, and I want my lawyer.” And remember, he adds, “Always turn your phone camera on. Record what is happening. Don’t let them intimidate you.”

This is easier said than done as anxiety among Latino communities across Maryland, which represent the third largest ethnic group in the state and make up approximately 11 percent of the population, is growing, and young people are experiencing it first-hand.

“My mom has been very anxious lately,” says “Monica,” a 17-year-old student attending the Saturday meeting with the Fulcrum. Her mother is from Nicaragua and does not have legal status in the U.S. despite being here for twenty years. “She is my protector, and I have never seen her this worried before.” “Monica,” born in the U.S., says that if her mom is deported, she will go live with her dad, a U.S. citizen. “I have many opportunities here, but if I were to leave with my mom, all her efforts would be in vain.” The Fulcrum uses a pseudonym for “Monica,” per her request.

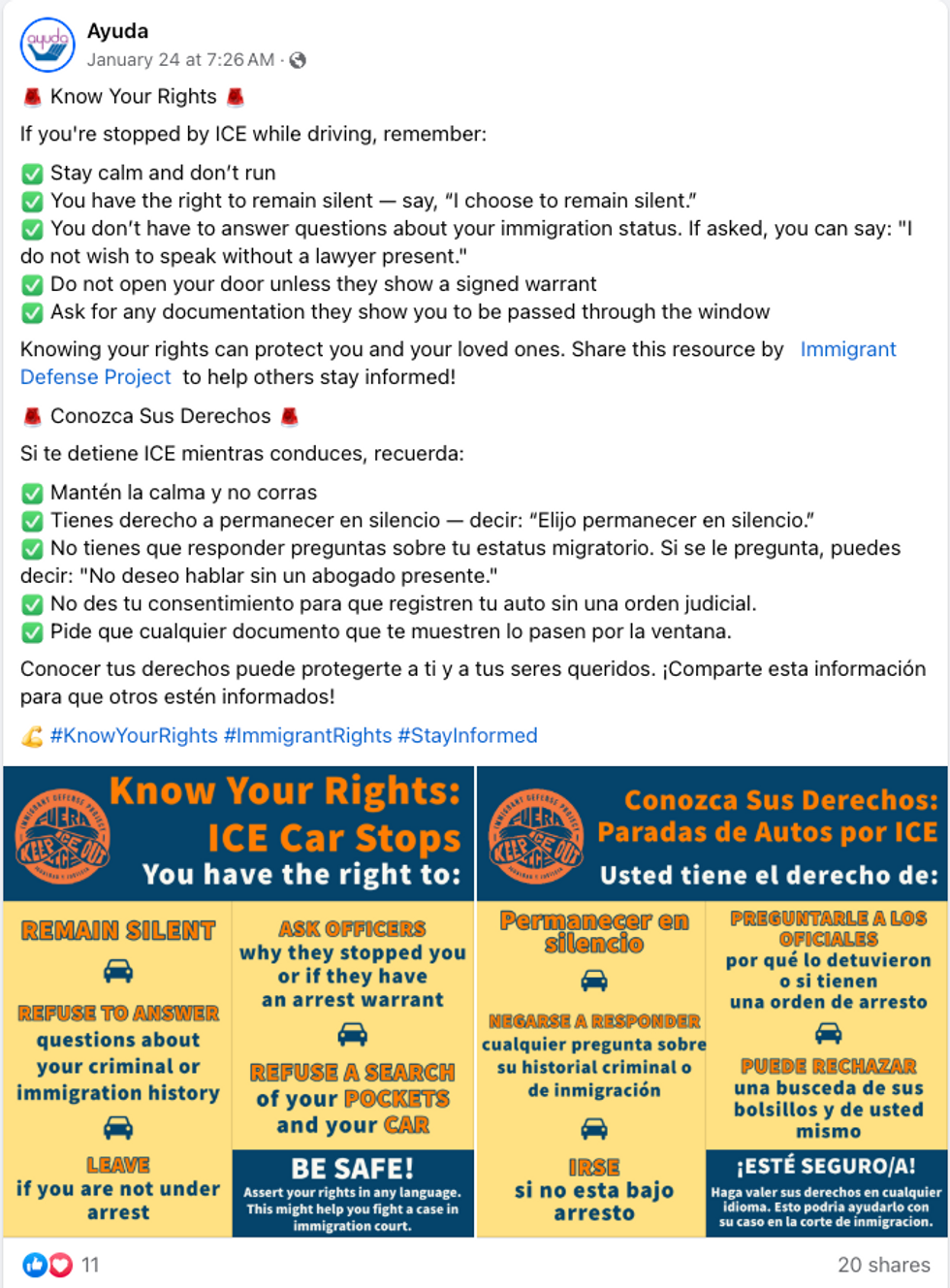

Across the state, schools host “Know your Rights” meetings like the one at a Montgomery County High School, which the Parent Teachers’ Association organized. Information is power, and Monica, as the editor of the Spanish language school newspaper, is leveraging her passion for journalism to launch a podcast in Spanish where immigrants can get answers to their questions from a network of pro bono lawyers. “People must educate themselves, and social media cannot be their only source of information. A podcast is accessible and low-cost.”

Resources like Ayuda are crucial for informing immigrants about their rights as ICE quietly expands its collaboration with local enforcement agencies through the 287 (g) Program, named after Section 287 (g) of the 1996 Immigration and Nationality Act. This allows the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to sign agreements with state or local enforcement authorities that authorize them to act as ICE agents. A fact sheet on the 287 (g) program by the American Immigration Council states that as of December 2024, ICE had agreements with 135 state and local law enforcement agencies across 21 states.

Though only three counties in Maryland have such agreements with ICE—Cecil, Frederick, and Harford counties—immigrant rights organizations are striking back hard to counter President Donald Trump's mass deportation agenda. In early February, CASA Maryland joined forces with other civil society allies and faith institutions to push for three bills to protect immigrants in Maryland. One of them, the Maryland Values Act, is aimed explicitly at terminating 287 (g) agreements in the state.

At a rally held in front of the Maryland State House on February 4th, Ashanti Martinez, Chair of the Maryland Legislative Latino Caucus, said in a press statement by CASA MD, “I know that all of us here understand what’s on our shoulders – the responsibility that we have to make sure that every family, no matter what your status is, feels protected, loved, seen, and valued here in Maryland. We value personhood more than status.”

The Protecting Sensitive Locations Act, the second piece of legislation introduced by CASA Maryland and allies, establishes clear guidelines for limiting ICE access to what are often referred to as “sensitive locations.” These include schools, courthouses, hospitals, places of worship, and other sensitive locations.

A win related to this motion came on February 24 th, when U.S. District Judge Theodore Chuang in Maryland ordered ICE not to conduct immigration enforcement actions “in or near places of worship.” The judge responded to a complaint filed by the Quakers and other religious groups about their constituents’ rights. While a setback for President Trump’s mass deportation agenda, the ruling applies only to one sensitive location.

The final piece of legislation is the Maryland Privacy Act, sponsored by state delegate Lorig Charkoudian and state senator Clarence Lam. This bill requires ICE to have a warrant to access Maryland residents' private state and local agency data. Under state law, undocumented immigrants can still obtain a driver’s license or identification card.

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

“This is a privacy bill to ensure the federal government cannot go through a fishing expedition in our state databases,” said Senator Lam at the Maryland State House rally. “This legislation really is about promoting transparency and promoting privacy. Marylanders have a right to know who’s attempting to access their data.”

In an interview with the Fulcrum, Stacey Brustin, a professor of law at Catholic University and a member of the advisory council for Ayuda, an immigrant rights organization in the Washington D.C. greater metro area, says that the biggest differences when it comes to immigration policy in the second Trump administration are “the targeting of sensitive locations, the stopping of enforcement priorities so that anyone can be a target and the diminishing access to legal representation while in detention.”

For Monica and other Latinos in Maryland, fighting back means overcoming the escalation of daily

trauma.“Fear creates stress, and stress creates illness,” says Beatriz to the Fulcrum, a woman in her 60s born in Colombia and now a U.S. citizen. “There is an emotional pandemic playing out in our communities, and I believe the consequences will be felt for years.”

Beatrice Spadacini is a freelance journalist for the Fulcrum. Spadacini writes about social justice and public health.