Nonprofit VOTE was founded in 2005 by a consortium of state nonprofit associations and national nonprofit networks to provide resources and trainings for the nonprofit sector on how to conduct nonpartisan voter participation and election activities. Nonprofit VOTE partners with America's nonprofits to help the people they serve participate and vote. We are the largest source of nonpartisan resources to help nonprofits integrate voter engagement into their ongoing activities and services.

Site Navigation

Search

Latest Stories

Join a growing community committed to civic renewal.

Subscribe to The Fulcrum and be part of the conversation.

Top Stories

Latest news

Read More

U.S. President Donald Trump (R) speaks with NATO's Secretary-General Mark Rutte during a bilateral meeting on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, on Jan. 21, 2026.

(Mandel NGAN/AFP via Getty Images/TCA)

Trump’s Greenland folly hated by voters, GOP

Jan 27, 2026

“We cannot live our lives or govern our countries based on social media posts.”

That’s what a European Union official, who was directly involved in negotiations between the U.S. and Europe over Greenland, said following President Trump’s announcement via Truth Social that we’ve “formed the framework of a future deal with respect to Greenland and, in fact, the entire Arctic Region.”

It’s been a bizarre start to the new year, with Trump ramping up his threats against the Danish territory — threats which included actual invasion — and any other NATO allies who sided with Greenland.

Trump’s post also announced invasion is off the table and he won’t be going ahead with the 10% tariffs he’d promised to levy on Denmark’s supporters on Feb. 1, more welcome news.

But still, European officials remain skeptical. “After the back and forth of the last few days,” Germany’s Vice Chancellor Lars Klingbeil said, “we should now wait and see what substantive agreements are reached between [NATO Secretary General Mark] Rutte and Mr. Trump. No matter what solution is now found for Greenland, everyone must understand that we cannot sit back, relax, and be satisfied.”

That lack of trust in America, and in particular the American president, is understandable, but deeply lamentable. When it comes to diplomacy, trust is a crucial currency, and to put it simply, we don’t have it.

Trump’s bombastic, reckless, and often dismissive rhetoric toward our allies would make anyone question our commitment, not to mention our moral compass. Whatever happens with Greenland in the coming hours, days, or weeks, Trump has — yet again — deeply damaged our relationships abroad and our standing in the world.

But here at home, the reaction among Republican lawmakers to Trump’s possibly premature Greenland news has been incredibly telling.

They are also relieved — relieved that this dumb ordeal may finally be coming to an end.

The last few weeks have put lawmakers in the unenviable position of having to answer whether they’d support a president who wanted to invade a sovereign territory that rightfully belonged to an ally.

They’ve also had to defend Trump’s utterly insane behavior, social media posts, and press conferences in which he seems truly deranged at times.

Consider what he texted the Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, in part, earlier in the week:

“Dear Jonas: Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize for having stopped 8 Wars PLUS, I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace, although it will always be predominant, but can now think about what is good and proper for the United States of America….

I have done more for NATO than any other person since its founding, and now NATO should do something for the United States. The World is not secure unless we have Complete and Total Control of Greenland. Thank you!”

Now, I won’t go through all of Trump’s demonstrably false statements here, nor will I point out how puerile and small our president looks. But needless to say, if you’re a Republican lawmaker, this embarrassing display of ignorance and fragility wasn’t a thing you wanted to defend.

Republicans also know how unpopular — like, really unpopular — Trump’s Greenland folly has been. A new Reuters/IPSOS poll found that his push to acquire the territory is sitting at 40 points underwater with the American electorate. To put an even finer point on it, that’s two points worse than Trump’s approval on the Epstein files.

The quicker Trump gets off Greenland, the quicker Republicans can get back to selling their domestic agenda in a crucial election year. And they were all too happy to get in front of reporters to express their relief that he wasn’t, in fact, going to take Greenland by force.

“I don’t think that was ever his intent, and so I’m glad he clarified,” said Speaker Mike Johnson.

“Most of us think it was crazy, with a few exceptions,” said Rep. Don Bacon. “Most of us thought, behind shut doors, he should be bragging on the economy that’s growing at 4.3%, wages climbing faster than inflation for the first time in four or five years. But now we’re talking Greenland.”

Hopefully not for much longer. Whatever Trump walks away with, which could be a “deal” that has already existed — will pale in comparison to the damage he’s done to our global reputation. Mineral rights? More bases? We could have negotiated all of that like a normal nation — and ally — would. Instead, Trump chose chaos and lunacy. The relief overseas and here at home that this nonsense might finally be over tells you just how dumb it was in the first place.

S.E. Cupp is the host of "S.E. Cupp Unfiltered" on CNN.

Keep ReadingShow less

Recommended

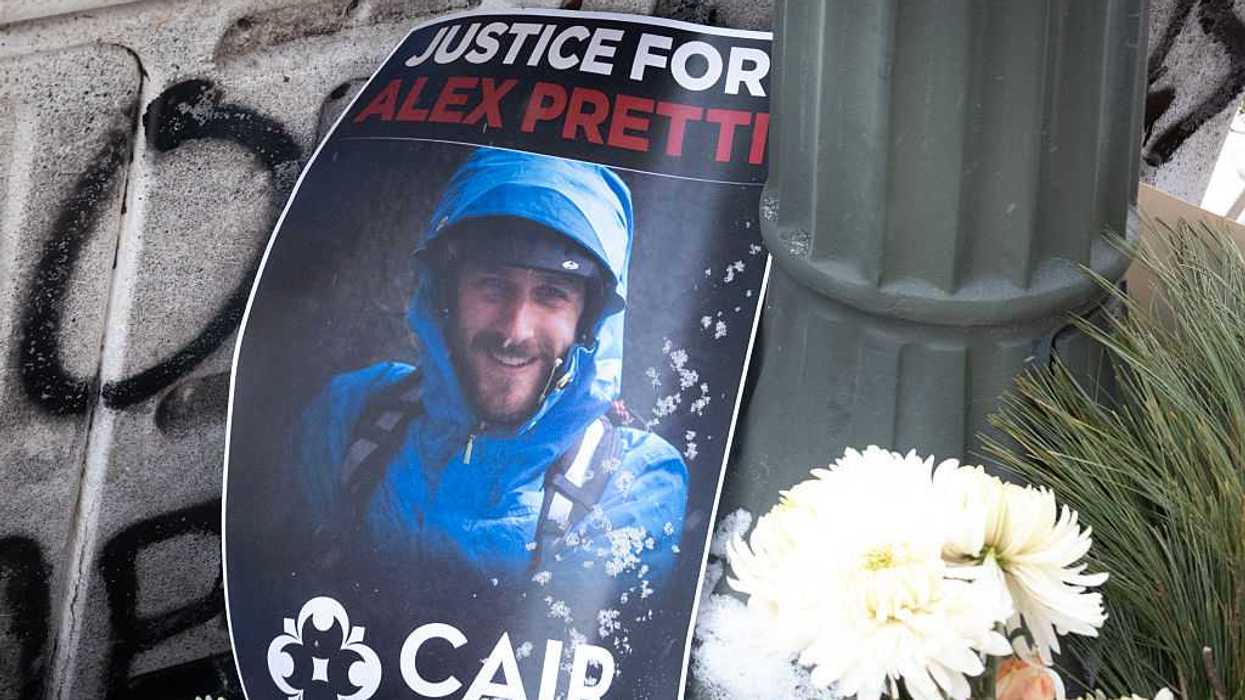

A picture sits at a memorial to Alex Pretti on January 25, 2026 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Pretti, an ICU nurse at a VA medical center, died on January 24 after being shot multiple times during a brief altercation with border patrol agents in the Eat Street district of Minneapolis.

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

The Resistance: Demanding a More Accountable Democracy

Jan 26, 2026

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, we are being asked to confront what kind of nation we still want to be. Anniversaries often invite celebration, but this one arrives at a moment when the distance between our founding ideals and our lived reality feels especially stark. That tension is painfully visible in Minneapolis, where the shooting deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti during federal enforcement operations have shaken public trust and forced a reckoning with the responsibilities of a government that claims to serve its people.

Good, a 37‑year‑old mother, was killed on January 7 when an ICE officer fired into her vehicle. The Hennepin County Medical Examiner ruled her death a homicide. Minneapolis Police Chief Brian O’Hara publicly contradicted early federal claims that Good had tried to run over an agent. That kind of discrepancy is not a small matter; it goes to the heart of democratic accountability.

Seventeen days later, Pretti — a nurse and lawful gun owner — was shot and killed by a U.S. Border Patrol agent during a separate operation. Federal officials initially claimed he violently resisted, but witnesses told reporters that the video showed an agent disarming him moments before the shooting. Pretti’s family said in a statement, appealing for people to ‘get the truth about our son.’

These deaths did not occur in isolation. They unfolded amid an expanded federal enforcement posture and growing tension between President Donald Trump and state and local government leaders. Minnesota Governor Tim Walz said the state was seeking full transparency and not shifting narratives. When state and local officials feel compelled to publicly contradict federal accounts, it signals a deeper institutional fracture — one that citizens cannot afford to ignore.

For many Americans, these events have become a rallying point. Civic groups, immigrant‑rights organizations, veterans who served alongside Pretti, and local residents are part of a renewed Resistance — a broad, citizen‑driven movement committed to defending democratic norms, civil liberties, and institutional accountability.

I support The Resistance and encourage others to do the same. Not as a partisan identity, but as a civic commitment to ensuring that government power remains answerable to the people. This is not a new idea. The country was founded on a distrust of unchecked authority. The Revolution itself was a response to a government that operated without accountability to those it governed. If democracy means anything, it means we don’t stay silent when the government kills people and won’t explain why. Silence is complicity — as old as the republic.

Democratic resilience depends on institutions that earn legitimacy through openness and accountability. The public response in Minneapolis reflects that understanding. Protests formed within hours of each shooting. Civil rights groups demanded independent investigations. Local officials challenged federal accounts. These actions are not signs of instability; they are signs of civic health. They show a public unwilling to accept ambiguity when lives are lost, and government force is used.

But civic outrage alone is not enough. If the 250th anniversary is to mean anything, it must be a catalyst for strengthening the systems that failed the families of Renee and Alex. That includes transparent investigative processes when federal agents use lethal force; clear communication between federal and local authorities; independent oversight mechanisms that the public can trust; and a renewed commitment to civil liberties in enforcement contexts. These are not radical demands. They are the basic maintenance of a functioning democracy.

Renee and Alex should still be alive. Their families should not have to fight for clarity about what happened. Their deaths remind us that the American experiment survives only when ordinary people insist that government power be exercised with restraint and accountability. The founders left us a framework, not a finished project. Two hundred and fifty years later, the responsibility to carry it forward is ours — and The Resistance, in its many civic forms, is one expression of that responsibility.

Hugo Balta is the executive editor of The Fulcrum and the publisher of the Latino News Network, and twice president of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

Keep ReadingShow less

New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani announces two deputy mayors in Staten Island on December 19, 2025 in New York City.

Getty Images, Spencer Platt

Young Lawmakers Are Governing Differently. Washington Isn’t Built to Keep Them.

Jan 26, 2026

When Zohran Mamdani was sworn in as New York City’s mayor on Jan. 1 at age 34, it became impossible to ignore that a new generation is no longer waiting its turn. That new generation is now governing. America is entering an era where “young leadership” is no longer a novelty, but a pipeline. Our research at Future Caucus found a 170% increase in Gen Z lawmakers taking office in the most recent cycle. In 2024, 75 Gen Z and millennials were elected to Congress. NPR recently reported that more than 10% of Congress won't return to their seats after 2026, with older Democrats like Sen. Dick Durbin and Rep. Steny Hoyer and veteran Republicans like Rep. Neal Dunn stepping aside.

The mistake many commentators make is to treat this trend as a demographic curiosity: younger candidates replacing older ones, the same politics in fresher packaging. What I’ve seen on the ground is different. A rising generation – Democrats and Republicans alike – is bringing a distinct approach to legislating.

At Future Caucus, we’ve helped more than 1,900 Gen Z and millennial lawmakers work on policy together since 2013, and the reality is that these young electeds, across Congress and statehouses, are better at passing bipartisan legislation. In 2023, Gen Z and millennial state legislators introduced 40% of all bipartisan bills signed into law, despite making up only 25% of state lawmakers. How are they overperforming so significantly?

Ideology is not disappearing. Young officials span the political spectrum, and plenty of them are deeply values-driven. But what they share in common is that many of them are living the same reality as their constituents: student debt, expensive housing markets, rising childcare costs, and wage instability in a rapidly changing economy being reshaped by AI. Those who are somehow not directly impacted by these forces still have a front row seat to their generation’s struggles.

Mamdani’s platform, for example, centered relentlessly on rent, childcare, and transportation. For many young lawmakers, affordability isn’t a sidebar issue, it’s the lens through which nearly every policy debate is viewed. Many of these leaders came of age watching financial crises, institutional failures, and political stalemates. Perhaps as a result, they are less sentimental about party theater and often more willing to test cross-aisle partnerships early, before incentives harden, in order to advance urgent policy priorities.

But here is the uncomfortable truth: Washington and state capitols aren’t designed for young lawmakers. Many face structural barriers that make staying in office difficult: low pay, limited staff capacity, and institutional models that assume outside wealth or exceptionally flexible careers. As a result, a troubling number of overperforming young lawmakers who are making an impact end up leaving office. Turnover drains committees of expertise, forces constant retraining, and weakens the very bipartisan relationships that make difficult legislation possible. America suffers when the very leaders who are turning the tide on toxic polarization and gridlock are the ones who choose to exit the system.

The opportunity for Washington is obvious: retention has to become a priority, not an afterthought. Without reforms that make public service sustainable, the very leaders showing the greatest promise for productive governance may be forced out just as they are becoming effective.

Some chambers are beginning to modernize: investing in staff capacity, expanding member support, improving safety protocols, and professionalizing a job that still assumes lawmakers have independent wealth or unusually flexible employers. If institutions don’t adapt, they will keep losing exactly the members they claim they want: pragmatic, coalition-oriented, future-focused leaders.

Party leaders and legislative managers have a choice. They can treat this rising generation as a rebrand opportunity with more diverse faces, better social media, and fresher slogans, while rehashing the same old constraining strategies and incentives. Or they can treat it as what it is: a chance to rebuild trust by making governing feel possible again.

This month’s swearings-in mark a measurable and generational shift in political leadership. Whether that translates into durable governing change will depend less on rhetoric than on institutional conditions: incentives for bipartisan work, room for policy experimentation, and the ability to retain talent over multiple terms. The signal is clear. The outcome is still unwritten.

Layla Zaidane is the president and CEO of the Future Caucus.

Keep ReadingShow less

Confusion Is Now a Political Strategy — And It’s Quietly Eroding American Democracy

Jan 26, 2026

Confusion is now a political strategy in America — and it is eroding our democracy in plain sight. Confusion is not a byproduct of our politics; it is being used as a weapon. When citizens cannot tell what is real, what is legal, or what is true, democratic norms become easier to break and harder to defend. A fog of uncertainty has settled over the country, quietly weakening the foundations of our democracy. Millions of Americans—across political identities—are experiencing uncertainty, frustration, and searching for clarity. They see institutions weakening, norms collapsing, and longstanding checks and balances eroding. Beneath the noise is a simple, urgent question: What is happening to our democracy?

For years, I believed that leaders in Congress, the Supreme Court, and the White House simply lacked the character, courage, and moral leadership to use their power responsibly. But after watching patterns emerge more sharply, I now believe something deeper is at work. Many analysts have pointed to the strategic blueprint outlined in Project 2025 Project 2025, and whether one agrees or not, millions of Americans sense that the dismantling of democratic norms is not accidental—it is intentional.

Some people describe the President as “ignorant,” a word they reach for out of frustration. But in my view, ignorance is not the issue. What looks like confusion or impulsiveness is often a strategy—one refined over decades. Public reporting has documented patterns of manipulating systems, refusing to pay vendors, challenging courts, and framing himself as a perpetual victim. These behaviors didn’t begin in the Oval Office; they simply gained a larger stage there.

I have come to believe that confusion is part of the plan. When leaders contradict themselves, rewrite history, rename institutions, or attack their predecessors, the public becomes disoriented. Confusion weakens vigilance. It makes people doubt their own understanding. And when citizens are overwhelmed, those in power face fewer obstacles to manipulating institutions, bending norms, and reshaping democracy to serve themselves rather than the nation.

The danger of a leader who rewrites the nation in this way is not limited to the moment. When a President renames institutions, erases traditions, mocks predecessors, or dismisses constitutional obligations, he is not just breaking norms—he is reshaping what future leaders may feel entitled to do. Democracies erode slowly, through repeated violations that become normalized.

People across the country are trying to make sense of what is happening. Yet we are watching other forms of democratic distortion take root—extreme gerrymandering that dilutes voters' will (Gerrymandering Explained | Brennan Center for Justice), and public attacks on the press that intimidate journalists and undermine the First Amendment’s core purpose: to ensure that citizens can question power without fear.

Commentators who repeat invented names — calling it the “Department of War” or the “Gulf of America” — must stop. When the media echoes language that has no legal basis, it risks normalizing it. Reporters have a responsibility to use the lawful, accurate names of our institutions, not the versions a president creates for political effect. Just because he says it does not make it legal.

Another part of this pattern is the effort to reshape government itself. We have watched a steady push to install people who will support the President’s goals, while removing or sidelining those whose job is to enforce transparency, ethics, or accountability. Inspectors general, career civil servants, and independent watchdogs exist to protect the public interest—not the interests of any one leader. When these positions are weakened or replaced with loyalists, the checks that safeguard our democracy begin to crumble.

We have also watched the President exert extraordinary influence over Congress even when he was not in office, shaping votes, intimidating dissent, and ensuring that lawmakers aligned with his goals. Now he openly signals his desire for a third term, and public reporting shows that several billionaires appear to be supporting efforts that could help consolidate his power (OpenSecrets. A leader who can influence Congress, weaken oversight, and command vast financial support can operate without meaningful restraint.

The Kennedy Center is not just another building in Washington. It was created by Congress in 1958 as the National Cultural Center, and in 1964—after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination—Congress amended the law to rename it the “John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts” (Public Law 88‑260). Because its name is established in law, no president has the authority to change it. Only Congress can do that. So, when a president claims to rename the Kennedy Center, alters signage, or encourages others to refer to it differently, he is not exercising legal power—he is attempting to rewrite history through spectacle and intimidation.

Even if his name is added to buildings or institutions, millions of Americans will not recognize it. The Kennedy Center will always be the Kennedy Center — a national memorial established by Congress, rooted in history, and tied to President Kennedy’s legacy. We will not normalize attempts to rewrite our cultural identity. We say the Gulf of Mexico, not the “Gulf of America.” We say the Department of Defense, not the “Defense of War.” A democracy survives when its people refuse to surrender language, history, or truth to political theater.

One of the clearest examples of this pattern came during a televised interview in May 2025. When the President was asked whether he must uphold the Constitution—the very document he twice swore to protect—he replied, “I don’t know.” That answer was not merely evasive; it was alarming. How can any leader raise their hand on Inauguration Day, swear an oath before the nation, and then claim uncertainty about whether that oath applies? For me, this was not ignorance. It was a performance of ignorance—a strategy that creates confusion, lowers expectations, and excuses behavior that would be unacceptable from any other public servant.

We are living through a moment when history, culture, and democratic traditions are being reshaped before our eyes. Citizens are not wrong to feel unsettled. They are not wrong to ask questions. And they are certainly not wrong to demand accountability from those who wield power in their name.

We must demand normalcy again. Not the normalcy of complacency, but the normalcy of functioning institutions, ethical leadership, and respect for the Constitution. Congress must act—not observe. Congress must restore what has been damaged, protect the legal names of institutions, rebuild the West Wing, and reassert its constitutional authority as a check on executive power. Congress must strengthen ethics laws, protect inspectors general, enforce transparency, and ensure that no president—current or future—can rewrite history, rename institutions, or operate outside the law.

The media must rise above attacks and intimidation. They must report what a president says, but they must not legitimize what is unlawful or invented. They must use the legal names of institutions, correct misinformation in real time, and refuse to normalize language that confuses or misleads the public.

Citizens must insist on accountability. They cannot pass laws, but they can force lawmakers to act. They must demand restoration of damaged institutions, support independent journalism, vote, speak out, and protect historical truth.

These solutions are not theoretical—they are doable. Congress already has the authority to pass laws and enforce oversight. Media outlets already have the tools to correct misinformation and maintain editorial independence. Citizens already have the power to vote, organize, pressure representatives, and shape public opinion. Democracy has been repaired before—after Watergate, after McCarthyism, after eras of corruption and overreach. It can be repaired again.

This is not a partisan concern. Millions of Americans in red, blue, and purple states are unsettled by what they are witnessing. Republicans, Democrats, and Independents — including some current and retired leaders in Washington — have expressed alarm at the erosion of norms, the rewriting of institutions, and the growing sense that our democratic foundations are shifting beneath us. The uncertainty is national, not ideological, and the responsibility to confront it belongs to all of us.

Confusion may be the strategy, but clarity is still our power — and democracy holds only if citizens refuse to let uncertainty become the new normal or allow its erosion to continue in plain sight.

Carolyn Goode is a retired educational leader who writes about ethical leadership, institutional accountability, and the concerns many Americans are expressing about the direction of the country.

Keep ReadingShow less

Load More