The latest interview in this series features Lilia Dashevsky, the founder and CEO of Emet Strategies, a new strategic communications firm. Lilia launched Emet after leading democracy efforts at CLYDE, where she worked with many of the nation’s leading democracy organizations and advocates in the country, supporting their communications efforts before and after the 2024 election.

I’ve long admired Lilia’s work. I’ve collaborated with her through my role at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins and followed her insights on the democracy sector. What stands out is her dual focus: the need to strengthen the sector’s communications infrastructure, and the urgency of thinking and acting differently at a potentially existential moment.

Having led pro-democracy organizations and initiatives for over 15 years, I’ve seen firsthand what Lilia describes: at best, communications are often marginalized, treated as secondary, or reduced to chasing media attention. Rarely are communications deployed strategically to achieve larger outcomes. Yet in today’s fractured political environment, where Americans inhabit increasingly different information ecosystems, communications are central if we hope to cultivate a public that cares about democracy itself.

An effective communications strategy cannot rely on writing and publishing op-eds in legacy news outlets (as great as that might be).

In our conversation, Lilia was candid about how the field needs to adapt. Three themes stood out:

- The field needs to test more —and embrace risk. Following the 2024 election, many organizations reverted to familiar tactics, including newsletters, talking points, and op-eds. Lilia worries this retrenchment has stifled innovation.

Lilia is adamant that the field needs to be willing to test out new types of communications- even if they might not work. People and organizations need to become more comfortable with the concept of risk.

As Lilia says, testing out new strategies is “just not happening as much as I think good communicators should be doing. “That ranges from everything that's basic to... What's my subject line? How am I going to run an A/B test all the way through?

How am I testing certain creative campaigns against my target audiences?

How am I iterating on my strategy based on the way that it's being received online, in the press, or elsewhere? I think there's a large hesitancy to do so, and I think part of that reason, as much as I love our funders in this space, has to do with the… ability for funders to say it is okay. If you fail, you do not have to have the most bind-up perfect communications campaign.” - The field does not truly know its audience: There is a tendency in this pro-democracy field to continually push out more content, without taking the time to understand who we are truly trying to reach. It may be easy to say that the sector should be trying to reach all Americans, but that’s not how effective communication works.

Lilia pushed on this point, pushing the field to both understand and diversify its audience. When an organization comes up with a strategic communications campaign, it’s incumbent upon them to do so while specifying who their audience is and attempting to diversify that audience.

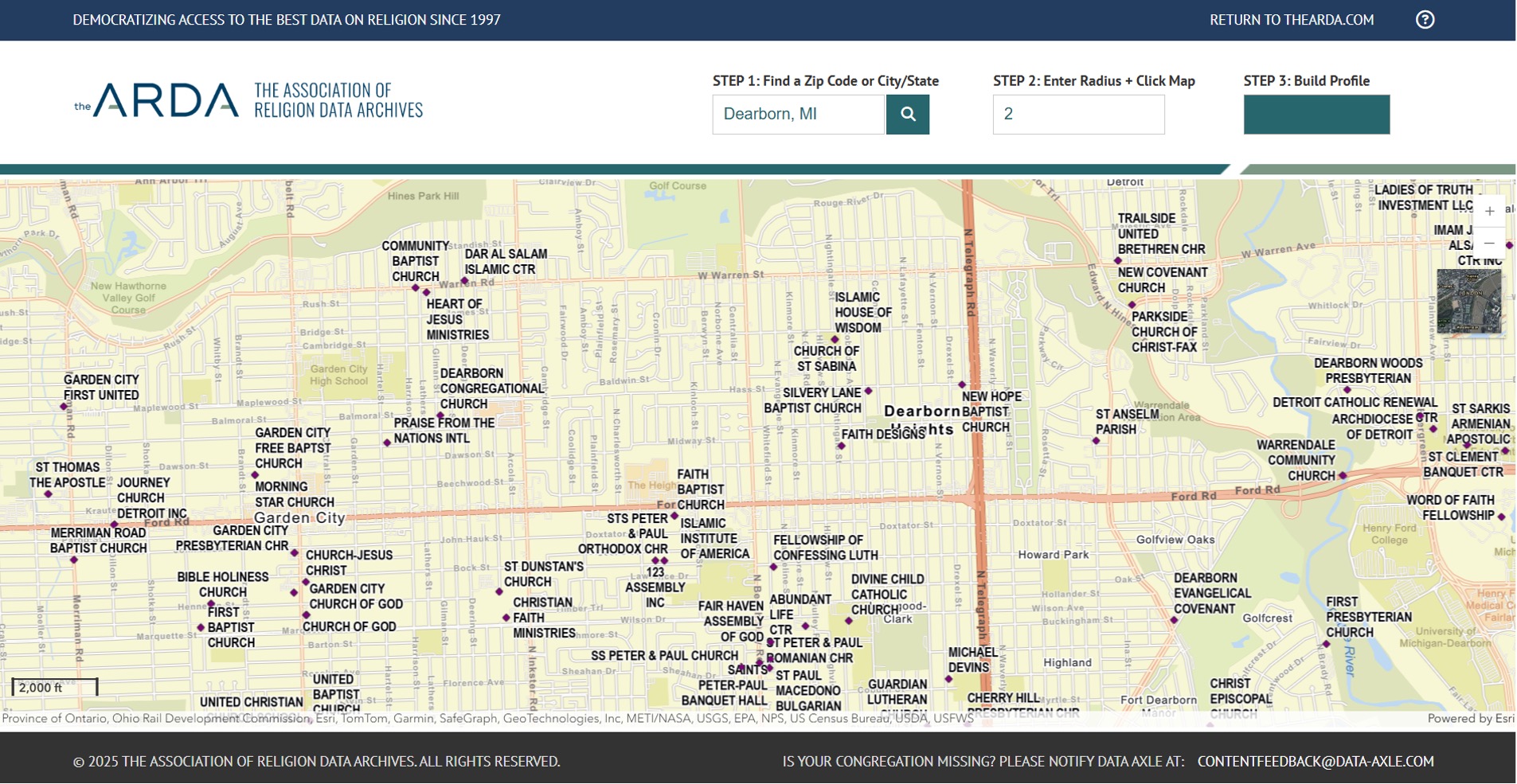

As Lilia notes, “We don't know who our audiences are. We make numerous assumptions about who they are, where they are, what they're reading, how they think, and what they're watching. But we don't have nearly the level of granularity about some of these audience-centric questions, the way that not only our peers and other nonprofit advocacy ecosystems do, but let alone our peers in the for-profit sectors do, and the way that they drill down on individuals and personas based off consumer habits, geolocation, and socioeconomic information. We are just not doing that.”

- We need to diversify the pro-democracy field and proactively learn from others. One of the topics I’ve touched on in previous pieces is the insularity of the pro-democracy ecosystem: there’s too much assuming that members of the field have similar ideological preferences, or too much talking to each other.

Leading up to the 2024 elections, for example, organizations spent considerable time developing talking points on how best to discuss elections. However, the target audience for these talking points was not clear at all. The danger was that all the pro-democracy groups spent a lot of time putting together talking points, sending them along, and then telling each other how great the talking points were received.

Lilia herself is trying to branch outside of the pro-democracy space as she starts her new practice. She is pushing others to approach the work with a sense of curiosity now: “What I'm advocating for is for organizations to a be curious and think a little bit- Oh, if I'm doing this one communication strategy, I wonder how somebody in the climate space is doing this, or I wonder if you know how my favorite brand might be handling this issue.

I would challenge everybody to critically evaluate the news that you are consuming each morning or each evening before you go to bed. I transitioned from receiving dozens of political newsletters in my inbox, which left me feeling overwhelmed, to now carefully curating newsletters that introduce me to new ideas, industries, and perspectives. I'm consuming information that most of the time has nothing to do with what I'm working on any given day.”

I left our conversation with a deeper appreciation for the role of communications in sustaining democracy. Lilia’s reflections are both a warning and a call to action: this work requires experimentation, a deeper understanding of our audience, and a willingness to learn from beyond our own echo chambers. I look forward to seeing how she builds Emet Strategies in the years ahead.

Scott Warren is a fellow at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University. He is co-leading a trans-partisan effort to protect the basic parameters, rules, and institutions of the American republic. He is the co-founder of Generation Citizen, a national civics education organization.