Iguanas may seem like an unconventional subject for verse. Yet their ubiquitous presence caught the attention of Puerto Rican poet Martín Espada when he visited a historic cemetery in Old San Juan, the burial place of pro-independence voices from political leader Pedro Albizu Campos to poet and political activist José de Diego.

“It was quite a sight to witness these iguanas sunning themselves on a wall of that cemetery, or slithering from one tomb to the next, or squatting on the tomb of Albizu Campos, or staring up at the bust of José de Diego, with a total lack of comprehension, being iguanas,” Espada told palabra from his home in the western Massachusetts town of Shelburne Falls.

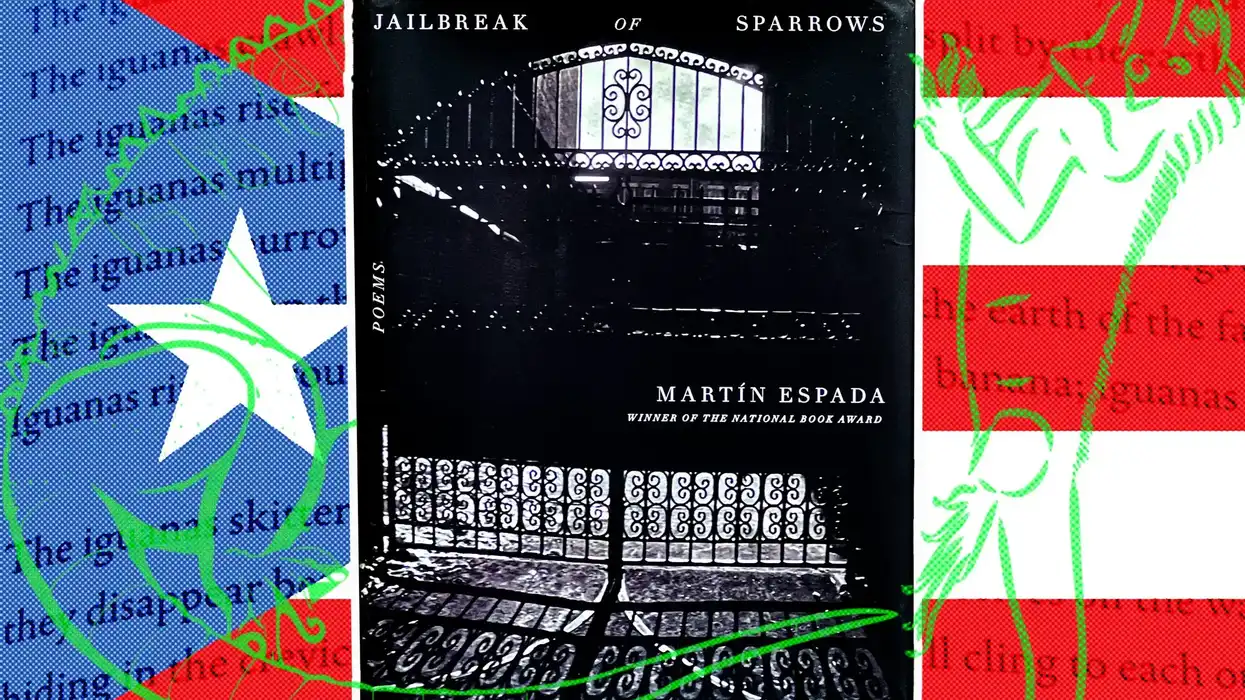

Espada, a National Book Award winner and an English professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, wrote a poem about that visit, “The Iguanas Skitter Through the Cemetery by the Sea.” Noting that the iguanas are an invasive species, he used them as a metaphor for colonialism. It’s the last poem in his new collection, “Jailbreak of Sparrows,” which was published this year.

“Jailbreak of Sparrows,” a collection of poems by National Book Award winner Martín Espada. Photo by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

“The green of the iguanas is the green of cash, the green of soldiers in uniform, the green of the lawns of the absentee landlords,” Espada explains. “It’s a way of bringing colonialism in Puerto Rico from the past into the present.”

As Espada explains, he bookended his latest volume with poems addressing Puerto Rico and its struggle for independence from the U.S. The book’s title is the namesake of the first poem in the collection, which addresses a mid-20th-century crackdown on Puerto Rican independence activists. The poem focuses on Utuado, a town in the central mountainous region of the island and where Espada’s father was born in 1930.“

During the suppression of a Nationalist (pro-independence) uprising in 1950, Utuado was bombed by warplanes, prisoners were shot, and no one in my family ever said a word,” Espada says. “I grew up with a family of storytellers, so I heard stories about everything … Certain stories pass from generation to generation, and others not. The silences tell us as much as the stories.”

As he writes in the poem, “No one spoke of the ammunition belts feeding the machine gun, the men bled like hogs for the family table, La Masacre de Utuado.”

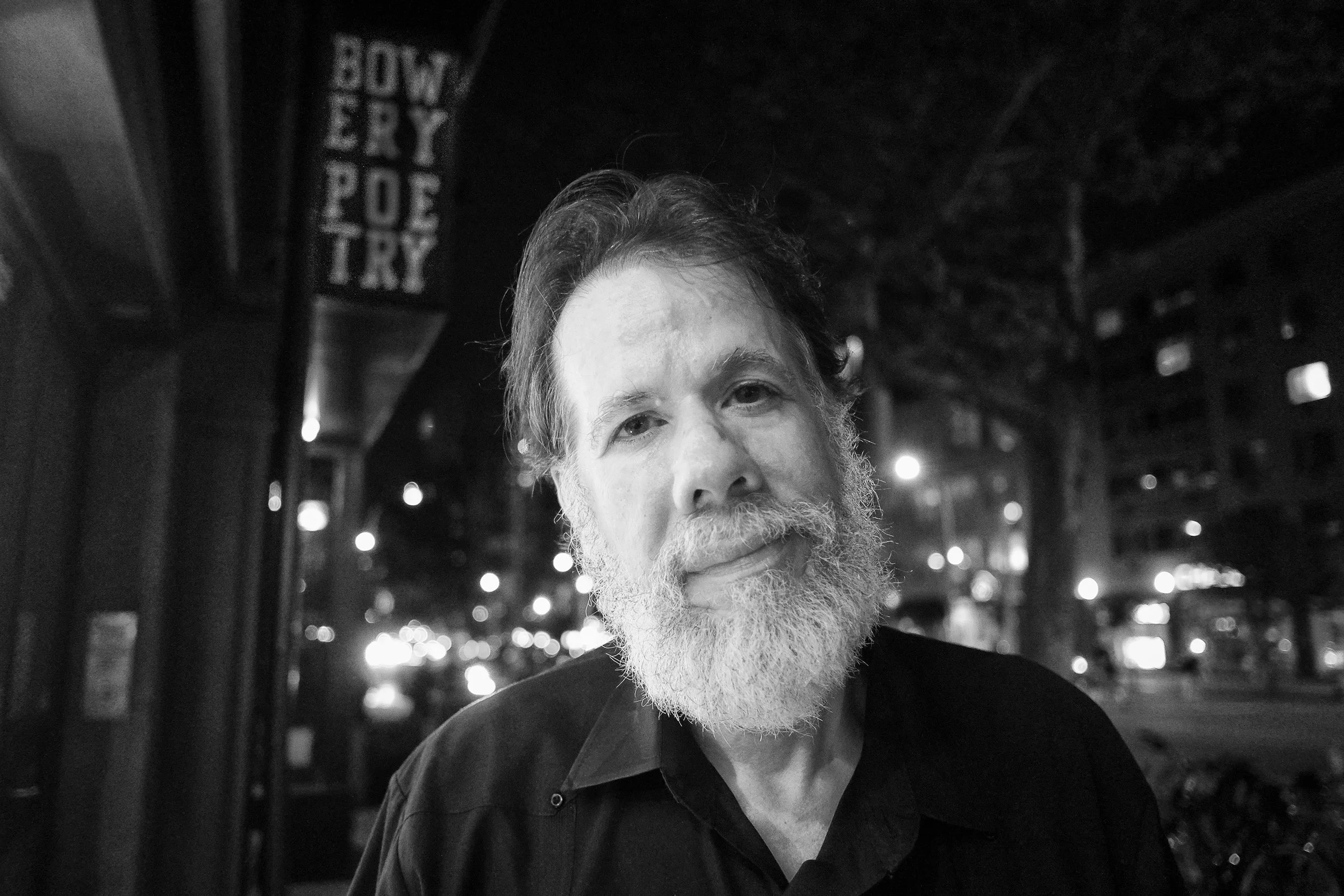

Poet Martín Espada, winner of the National Book Award. Photo by David González, courtesy of Martín Espada

Within the pages, there’s also “Big Bird Died for Your Sins,” a poem about a younger Espada’s reaction to the death of Puerto Rican Major League Baseball star Roberto Clemente in 1972. Clemente died in a plane crash trying to bring relief supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua.

Espada was already feeling out of place when his family moved from the diverse neighborhood of East New York to the more suburban Valley Stream, on Long Island, New York. Anguished over Clemente, he sought solace playing basketball with peers who included a tall-for-his-age rival nicknamed Big Bird.

Big Bird punctured his grief, claiming that the only reason for Clemente’s speedy induction into the Hall of Fame was that he was Black and Puerto Rican. Angered, Espada lashed out with physical play and plenty of elbows. Later in life, he reflected that Big Bird was likely repeating comments from his father.

“Racism is not innate,” Espada says. “Racism is learned. The fathers in the living rooms of Valley Stream watching those ballgames said what they said right in front of the kids, who then said what they said right in front of me. The poem has something to say about the nature of racism, the way racism spreads from person to person, household to household, generation to generation.”

A segment of “The Iguanas Skitter Through the Cemetery by the Sea,” from Martín Espada’s poetry collection “Jailbreak of Sparrows.”

Other poems in the book address accounts of the police fatally shooting young Latinos – Eddie Irizarry in Philadelphia in 2023 and Mario González Arenales in Alameda, California, in 2021. In the same section, Espada tweaks President Trump through a poem about a poem – specifically, “The Snake,” which Trump has read at multiple campaign rallies. Trump used the poem’s narrative as a metaphor for undocumented migrants: A kindly woman finds a suffering snake, takes it in and cares for it, only for the now-healthy reptile to fatally bite her, saying, “You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in!”

Espada examines the history of the poem, which, he says, is actually a jazz song based on an Aesop fable. To him, the real snakes are the menacing machinery at slaughterhouses in the U.S. that employ underage migrant youth. The workers’ exhaustion from long hours and their acid-burned forearms got their teachers concerned enough to alert the authorities, resulting in a CBS News 60 Minutes exposé.

There is also a section of love poetry dedicated to Espada’s wife, Lauren Marie Espada. They are presented as love songs from animals, objects, even the polar bear mascot of a minor league baseball team affiliated with the Boston Red Sox.

Throughout, Espada captivates with mesmerizing scenes and imaginative comparisons.

“My work is associated with a certain political stance, and that is as it should be,” he says. “By the same token, what I am discovering as I mature, and I’m now 68 years old, is that there are indeed many voices inside this head, and I don’t mean delusions. I mean poetics.”

Iguanas on the Tombstones: A Poet's Metaphor for Colonialism was first published on palabra and was republished with permission.

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in a variety of media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Tenorio is also a cartoonist. @rbtenorio

Patricia Guadalupe, raised in Puerto Rico, is a bilingual multimedia journalist based in Washington, D.C., and is the co-managing editor of palabra.