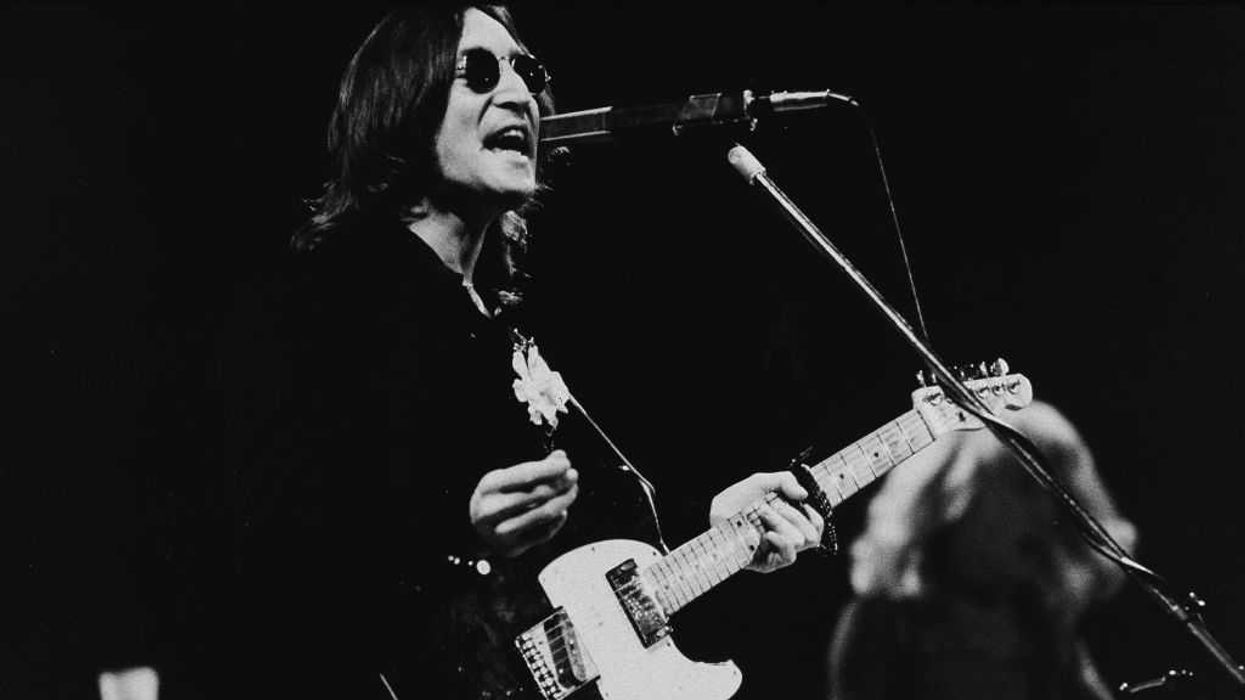

Everyone knows John Lennon’s “Imagine.”

It floats through Times Square on New Year’s Eve, plays during Olympic ceremonies, and fills the air at corporate galas meant to celebrate “unity.” Its melody is tender, its message is simple, and its premise is seductive: If only we could imagine a world without possessions, borders, or religion, we would live in peace.

But what’s striking is how this became the Lennon song the world remembers — and how much of his genuinely radical work has been forgotten.

Ask most people about “Working Class Hero,” “Power to the People,” “Gimme Some Truth,” or “I Don’t Wanna Be a Soldier, Mama,” and you’ll likely get blank stares. Those songs burn with class anger, anti-imperialism, and contempt for power. They were written in the same era as “Imagine,” yet they’ve been buried beneath the soft fog of its sentimental idealism.

In “Working Class Hero,” Lennon dismantles the myth of social mobility, describing how capitalist society trains us to obey, to consume, and to mistake conformity for success. “They keep you doped with religion and sex and TV,” he spits, “and you think you’re so clever and classless and free.” It’s not a dream of peace — it’s an autopsy of oppression.

In “Power to the People,” he does something almost unthinkable for a pop icon: He demands collective revolt. It’s a chant, not a prayer — a direct call for working-class empowerment and political participation. And in “Gimme Some Truth,” Lennon channels his fury at the political deceit of the Nixon years: “No short-haired yellow-bellied son of Tricky Dicky gonna mother hubbard soft-soap me.” It’s not polite, and that’s the point.

And then there’s “I Don’t Wanna Be a Soldier, Mama,” one of Lennon’s most underrated political statements. Built around a grinding, repetitive groove, it’s less a song than an act of refusal — a mantra against every institution that turns people into instruments of power and war. “I don’t wanna be a soldier, I don’t wanna die,” he wails, then widens the rejection: “I don’t wanna be a lawyer or a liar.” The repetition becomes defiance itself — a protest against being molded, conscripted, or defined by a system that sees human beings as roles to fill, not lives to live. It’s the sound of exhaustion turned into resistance.

These songs confront the listener; “Imagine” comforts them. One is a hammer, the other a lullaby. And of course, it’s the lullaby that the establishment has chosen to keep alive.

And it’s easy to see why.

“Imagine” offers hope without conflict, empathy without action, peace without politics – and all under the illusion that the statement is radical because it comes from a respected rebel. It takes the rage of the oppressed and converts it into a vague moral wish — a clean anthem for a world that has no intention of changing.

Because in “Imagine,” the problem is not power but belief; not systems of exploitation, but ideas that divide us. The remedy, the song then suggests, is not to organize or resist, but to dream a bit harder. Maybe much harder as the times worsen. In a sense, the song’s utopianism turns revolt into fervent reverie and, in that way, flatters the listener into thinking that moral clarity is somehow a substitute for struggle.

That’s why “Imagine” survives while “Working Class Hero” fades. It’s safe. It doesn’t indict anyone. It doesn’t name enemies. It can be played by a bank, a billionaire, or a government agency because it asks nothing of those who are listening. The same culture that once feared Lennon now packages him as a prophet of contentment — a brand ambassador for harmony.

In the early 1970s, Lennon’s activism was taken so seriously that the U.S. government tried to deport him. The Nixon administration feared his anti-war influence and had the FBI wiretap his phones, tail him, and use a minor drug conviction in Britain as a pretext to deny his green card. (Sounds familiar?) For years, Lennon fought surveillance, harassment, and expulsion — a campaign of intimidation meant to silence a political threat. (After Nixon resigned, the case was dropped, and in 1976 Lennon finally received his green card.)

But now, that same state and the culture that supported that state (the so-called “Silent Majority”) that once saw him as dangerous routinely plays his softest song at public ceremonies.

The irony is that Lennon understood exactly how power works. He sang about propaganda, class exploitation, and the way systems domesticate dissent. But in the end, his one song that has gained iconic cultural status is not a rebellion song but the sound of a rebellious voice neutralized — a once-dangerous voice absorbed into the background music of the very world it meant to change.

Ahmed Bouzid is the co-founder of The True Representation Movement.