Toscano is an attorney and a former Democratic leader in the Virginia House of Delegates. He is the author of “ Fighting Political Gridlock: How States Shape Our Nation and Our Lives.”

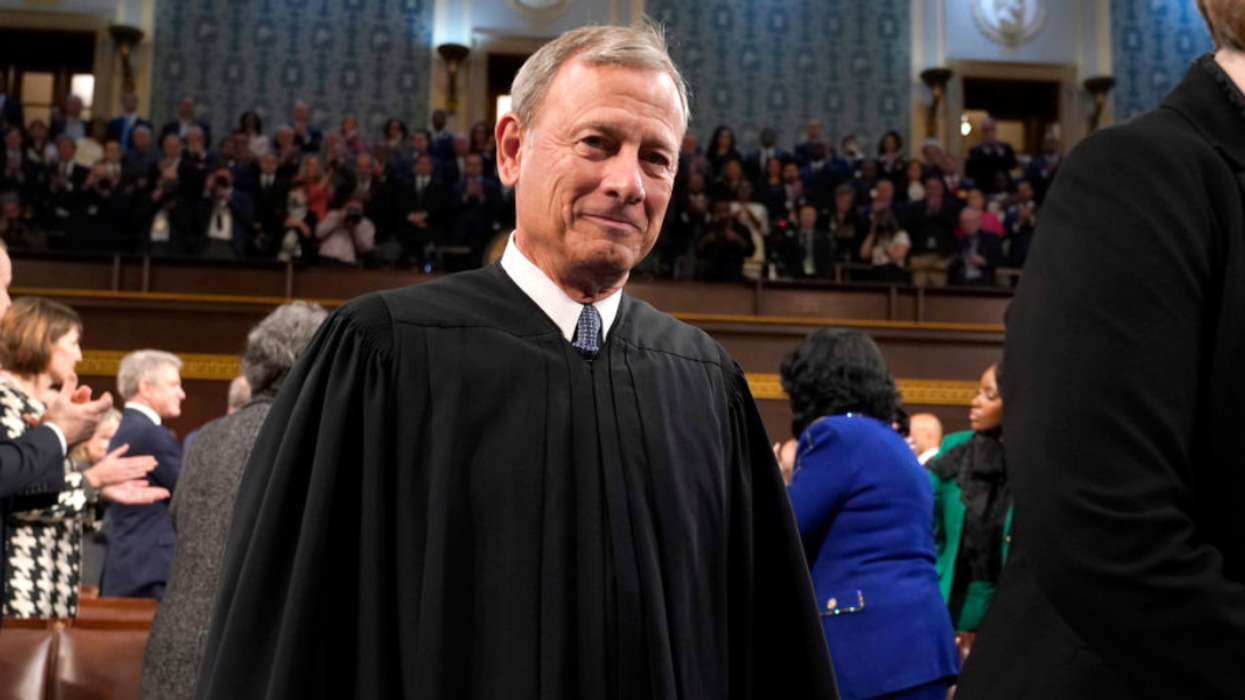

Defenders of democracy had hoped the Supreme Court decision in Trump v. United States would begin with the words “No man is above the law.” But Chief Justice John Roberts avoided the phrase entirely in his 43-page opinion. Instead, he produced an astonishing and convoluted treatise that denigrates a key principle of our jurisprudence championed by the founders and celebrated by the vast majority of Americans for 250 years.

In MAGA world, champagne corks were popping, as the court provided former President Donald Trump one more way to avoid legal accountability. But this decision is more than just about Trump; it arguably has done more to concentrate power in the presidency than any single act in history.

And it opens the future possibility — even if we get past Trump — that any demagogue could win power in a national election and cement it in a dictatorial fashion for decades. In their glee, conservatives are not thinking about the long-term implications of the decision and the threats to liberty that are raised by it.

The broadest immunity

One could understand some limited immunity granted to a president. But the Supreme Court went much further, opening the door to actions that few Americans would find acceptable and would never be justified by the founders. Roberts accuses the three dissenters — Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown-Jackson—of striking “ a tone of chilling doom,” but his opinion is really the cause for alarm. With this decision, a president now has complete immunity for any action under the powers granted by the Constitution itself. Those actions are “conclusive and preclusive” and thus cannot be prosecuted.

This includes Article II powers whereby the president “shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States.” As Commander in Chief, could Trump, Joe Biden or some future president order the military to assassinate a political opponent? What about an entire group of people with whom the president disagrees? Could the military be ordered to fire upon people trying to cross the border? How about ransacking the headquarters of a political party for “allegedly plotting a takeover of the government”? Or seizing the files of prominent journalists in the name of national security? Or widescale surveillance of telephone and internet accounts to preserve domestic order? These threats to life and liberty cannot simply be swept under the rug, no matter the president. This list goes on and on. And little can be done about it.

The majority opinion also creates an entirely new standard that grants the “ presumption of immunity ” for “an official act unless the Government can show that applying a criminal prohibition to that act would pose no ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.’” That makes accountability even more problematic. Presumptions are not easy to rebut, and it is not clear who makes that decision. Would it be a prosecutor, a judge or a jury? And since the opinion states a court cannot inquire into the motives behind the act itself, the proof necessary to rebut may be an unattainable bar to overcome.

There are suggestions in the opinion that discussions between the president and other executive officers (e.g. Trump asking the vice president not to certify the electors or discussions with his attorney general about overturning the election) might be immune as well. The majority opinion is especially chilling because it implies that former President Richard Nixon might have found a legal way to prevent the Watergate tapes from being disclosed or used in a prosecution.

Justice Amy Coney-Barrett is the only one in the majority who actually is willing to look closely at Trump’s actual acts to see if these new standards of immunity would apply. While she concurs with the majority, she asserts “the President’s constitutional protection from prosecution is narrow,” and argues that since the “President has no authority over state legislatures or their leadership … it is hard to see how prosecuting him for crimes committed when dealing with the Arizona House Speaker would unconstitutionally intrude on executive power.” (Trump unsuccessfully implored Speaker Randy Bowers to call a special session of the Legislature to discuss nonexistent election fraud in the state.)

Further, she agrees with Special Counsel Jack Smith’s argument to the court that it should immediately determine Trump’s immunity claim in the specific case. Finally, she objects to the majority’s position that would bar the use of protected conduct as evidence in a criminal prosecution of a president. One wonders why she voted with the majority.

The hypocrisy of ‘originalism’

The decision forever exposes the hypocrisy of the self-proclaimed “originalists” on the court, who constructed their argument to suit their political agenda, without recognizing the legitimate concerns about its impact beyond Trump. As Sotomayor’s dissent makes clear, the founders could have included an immunity clause in the Constitution but chose not to do so.

They were aware that such protections were granted to some governors in their original state constitutions. But no such immunity claim was included in our founding document, perhaps out of concern for the return of a monarchy. The founders were worried about executive power and created our checks and balances within the separation of powers to guard against it. Today, executive power is more concentrated than ever, and the Supreme Court has now blown away a key way to hold it accountable. Jefferson, Madison and even Hamilton are undoubtedly turning over in their graves.

Is there any silver lining?

Legally, this decision is a disaster. But politically, it may have some value. First, Jack Smith may push for an evidentiary hearing in the D.C. Circuit Court to determine whether Trump’s actions around Jan. 6 and its aftermath fall outside the presumptive immunity granted by the court. It would not be a trial, but could allow the public to review his actions to overturn the 2020 election. Those hearings could continue into the fall.

But more importantly, like the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the decision might galvanize those who worry about another Trump presidency. The ex-president cannot really be defeated by court actions; our best chance has always been at the ballot box.

Franklin once referred to the product of our constitutional convention as “a Republic, if you can keep it.” The November election may be one of the last chances to do so.