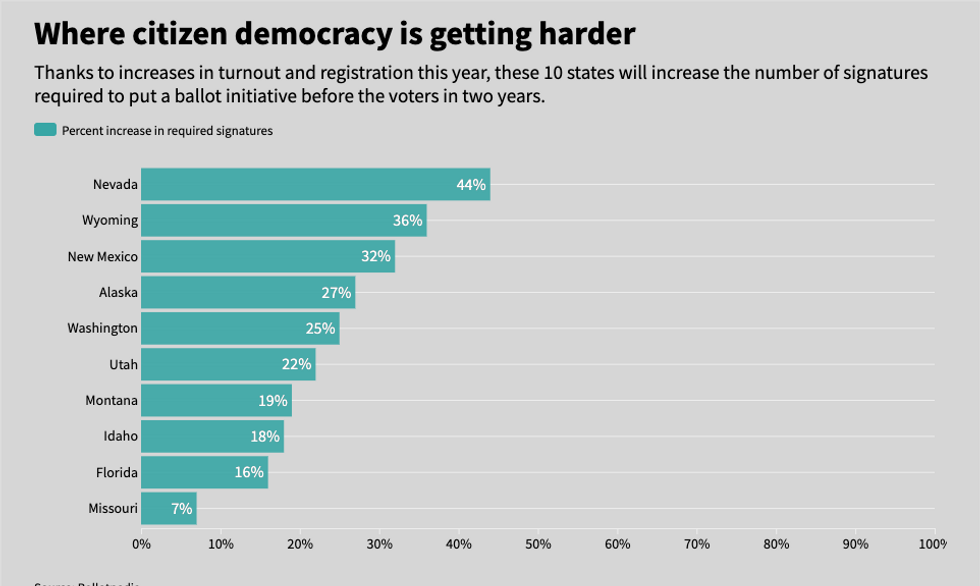

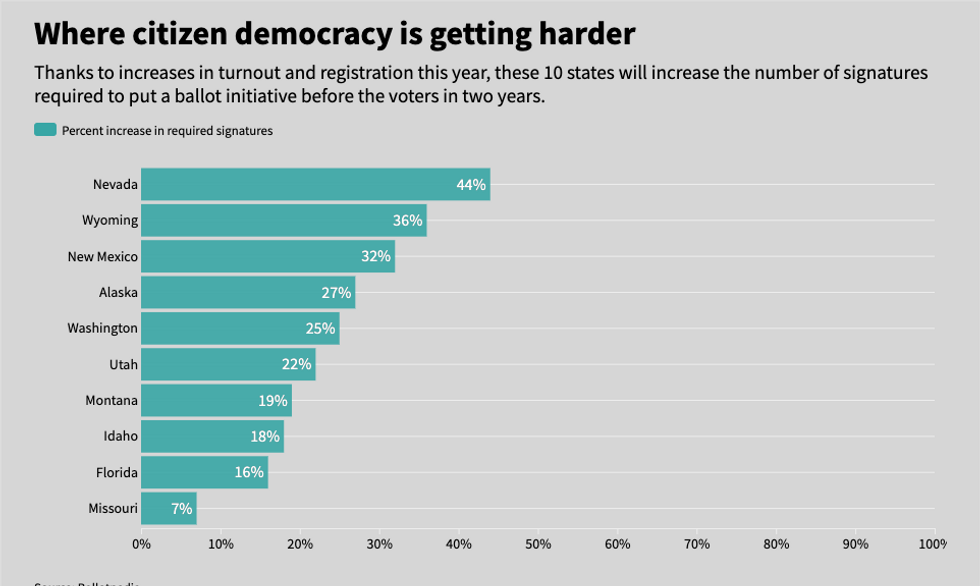

The irony seems obvious: One consequence of the burst in voter participation this year is that it will be tougher for those same voters to participate next time.

Half the states give their people a shot at putting proposals to a statewide vote, the sort of citizen-driven democracy that many good-government voices say should be much closer to the rule than the exception. In 10 of those states, which are home to about one in six Americans, the petition signature minimums for getting referendums on the ballot are tied to recent turnout and registration numbers.

No surprise after an election when the highest share of eligible people voted in more than a century, the 2020 figures went up in all 10 states. But here's the surprise for those unfamiliar with the legal quirk: Millions more people will need to sign on to proposed plebiscites starting next year or else the measures won't be considered.

These so-called direct democracy measures amounted to one-third of the 129 ballot initiatives put to a vote across 34 states in November. (The rest get placed on the ballot by legislatures.) The number was much lower than at any other time in the past decade — according to a new report from Ballotpedia, a digital encyclopedia of American elections — almost surely a consequence of the coronavirus pandemic. Only 5 percent of campaigns to gather signatures succeeded, in part because more than two dozen were abandoned in the face of the Covid-19 outbreak.

But the proposals from the public that did get considered generated $935 million in donations and campaign spending, by Ballotpedia's estimate, almost four-fifths of all the money raised and spent on 2020 ballot measures.

While taxes was the most popular topic, with 26 measures overall, proposals to change campaign finance rules, redistricting authority or other election rules was second at 18.

Source: Ballotpedia

Source: Ballotpedia

Looking forward, the threshold for future citizen-initiated ideas will grow most dramatically in Nevada — 44 percent.

That's because the state's complex law factors the previous two elections, not just one. Turnout in the fast-growing state soared in 2018 thanks to highly competitive contests for governor and the Senate, then rose significantly again this fall after the presidential battleground responded to the coronavirus pandemic by sending every active registered voter a mail-in ballot.

At the same time, however, the spread of Covid-19 crushed prospects for one of the year's premier ballot measures, which would have created an independent commission to draw Nevada's congressional and legislative boundaries in time for the nationwide redistricting that starts next year. After the courts ruled that electronic signatures could not count, advocates collected only a fraction of the 980,000 required. And from now on the minimum will be 141,000.

The requirement will grow 16 percent, or more than 199,000 signatures, in another fast-growing state: Florida, which is also by far the biggest state where citizen democracy's prospects in the future are driven by participation in the past.

It permits people to propose amendments to the state constitution, with 60 percent supermajorities required, and two of the most prominent have been on the ballot in recent years. In 2018 the state voted to allow almost all former felons to resume voting after they are through with prison, probation and parole — a list to which the Legislature has now added payment of fines and other court costs. Last month the majority of 57 percent was not enough to open the state's primaries to all voters, the top two finishers advancing to November regardless of party.

The other states where citizens may propose ballot measures do not tie their minimal signature requirements to the most recent turnout — and the current ranges are from 17,000 in South Dakota to 59 times that amount, or 997,000, in California.

Most base the number on the total votes cast in the last governor's race. But, either way, the paradoxical result is similar: Only fewer votes for candidates from one year to the next will mean an easier road for initiative-writers.

After turnout for the 2014 midterm plunged to its lowest level since World War II, the thresholds dropped 11 percent nationwide — and the number of citizen initiatives and veto referendums more than doubled, to 76 on statewide ballots in 2016.