Barrett i s a communications consultant and advisor to Square One Politics, a Democratic campaign consulting firm. He's also on the advisory board of DoSomething, which promotes civic engagement by young people.

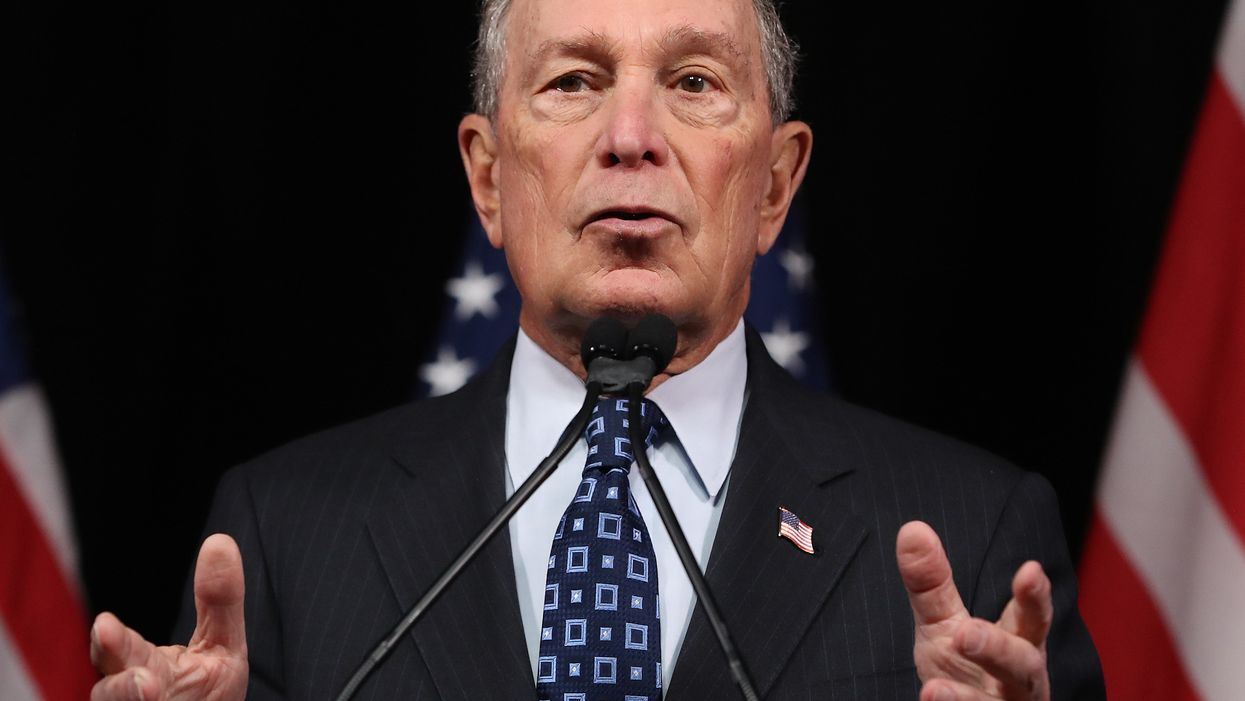

Chaos. That is Mike Bloomberg's strategy for 2020. And after Iowa he has what he wants.

Smart billionaires don't keep airing national commercials of their bus driving through America — unless they know the path. That path doesn't seem clear to everyone right now, but it is. And every domino is falling in the right direction for it.

How we got to this path is decades in the making, involves a lot of money and should make you want to punch through a wall like the Kool-Aid Man. Because at the core of Bloomberg's apparent strategy is something antithetical to a functioning democracy. He doesn't actually need your vote. He doesn't need to win a single state in the primary. He has enough money to circumvent the entire process, to sustain a losing campaign until it becomes viable or hang around long enough to do something even worse for democracy.

So, what is he up to, really? First of all, the discussed Bloomberg strategy isn't the real strategy.

In 2008, Rudy Giuliani famously chose to skip Iowa and New Hampshire and bet his campaign for the Republican nomination on Florida and Super Tuesday. It didn't work. It has never worked.

Bloomberg has to claim that as his strategy because he got in late. There was no time to put together a credible ground game in the early states. He won't be a factor in the New Hampshire primary on Tuesday, and don't expect him to win Nevada or South Carolina either. But he can gain a few delegates along the way.

And that's the real strategy.

It will take 1,990 of 3,979 pledged delegates to win the Democratic nomination on the first ballot. Delegates are proportionately distributed based on the share of the vote each candidate receives in the primaries and caucuses. States are not winner-take-all. But you do have to get 15 percent in a contest to claim any delegates.

In a crowded field there's a greater likelihood no one gets to 1,990. Then what happens? The convention goes to a second ballot, when the winner needs 2,376 of the 4,750 delegates. Wait. How are there now more delegates?

Because the superdelegates are allowed to vote. These people, mostly elected and appointed party officials, are not bound to any candidate.

In theory, they are meant to be a balance in case the pledged folks push for a candidate someone party leaders don't view as viable. You can see where many would find their mere existence unfair. After a long fight with the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign over the fairness of keeping superdelegates, the party decided to prevent them from voting on the first ballot this time.

It seems fair. But the unintended consequence is that those superdelegates are no longer available to mitigate chaos and push the delegate leader over the threshold on the first try.

If five or six viable candidates remain in the race through March, a brokered convention is likely. And there, as at a caucus, delegates would be free to migrate toward whomever everyone in the room decides would have the best chance of winning in November.

That could lead to further chaos and distrust. There's already so much focus on the presidential race, even as dozens of critical House and Senate seats are at stake. A brokered convention would lead to even less focus on down-ballot races.

The scenario for a brokered convention is not far fetched.

Joe Biden doesn't seem like he'll give up easily, even after a poor showing in Iowa. Sanders has already proven he will fight to the end as he did in 2016. Elizabeth Warren is consistently grabbing at least 15 percent of the vote in most states and has vacillated between being a contender and the front-runner at times. Pete Buttigieg is strong in some regions of the country and facing an uphill climb in others, mainly places like upcoming South Carolina.

Amy Klobuchar will grab delegates in the Midwest and some elsewhere, and Andrew Yang has a strong enough following to matter and be pivotal at the convention — although they are most likely to exit before the end of March. Then there's another billionaire, Tom Steyer, who can stay in as long as he wants because he's self-funded.

There's a real scenario in which eight people are grabbing delegates through March, including Bloomberg. Simple math will tell you, if that's the case, no one is reaching 1,990.

If Biden fades, the party's moderate wing will look to Buttigieg but he's an unknown. It both works in his favor and doesn't. His low numbers with African-Americans could worry party voters about his chances in a general election. There will be people worried that either Sanders or Warren are too far left and can't win the general election either.

And here sits Bloomberg, casually saying all the right things. He has pledged to keep his staff of 1,000 people on through November to support the eventual nominee. He has vowed to do whatever he can, with his vast media assets, to defeat President Trump.

But make no mistake, he's counting on and facilitating a brokered convention. Mike Bloomberg doesn't have to win a single state to become the nominee. And that should scare you. He has the money and resources to remain in the campaign even if he's in seventh of eight places, a luxury almost no candidate has ever had. Campaigns are expensive and the second you lose momentum that money usually goes away quickly.

Mike Bloomberg represents the billionaire savior, something we have glorified in this country. But, as Hasan Minhaj brilliantly laid out, billionaires won't save us. The philanthropist who has enough money and good ideas to help the poorest Americans is not new. It exists all along the ideological spectrum, from Bill Gates on the left to the Koch family on the right.

When there's chaos, everyone will look for a savior, someone outside of a confusing fray — someone like Mike Bloomberg. He's counting on that. And he doesn't have to count on your vote. That is flat bad for democracy.