What the century scholars call “ the democratic century ” appears to have ended on January 20, 2025, when Donald Trump was sworn in as America’s forty-seventh president. It came almost one hundred years after German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolph Hitler as Chancellor of Germany.

Let me be clear. Trump is not America’s Hitler.

He is a duly elected president entitled to his views of the presidential power that he is authorized to exercise under the Constitution. As the New York Times explains, “President Trump’s expansive interpretation of presidential power has become the defining characteristic of his second term.”

It is right to say that he has launched a “second American Revolution.” Many Americans think he is bringing much-needed change to Washington, and, as columnist Bret Stephens observes, displaying the kind of “energy in the executive” that the U.S. Founders valued.

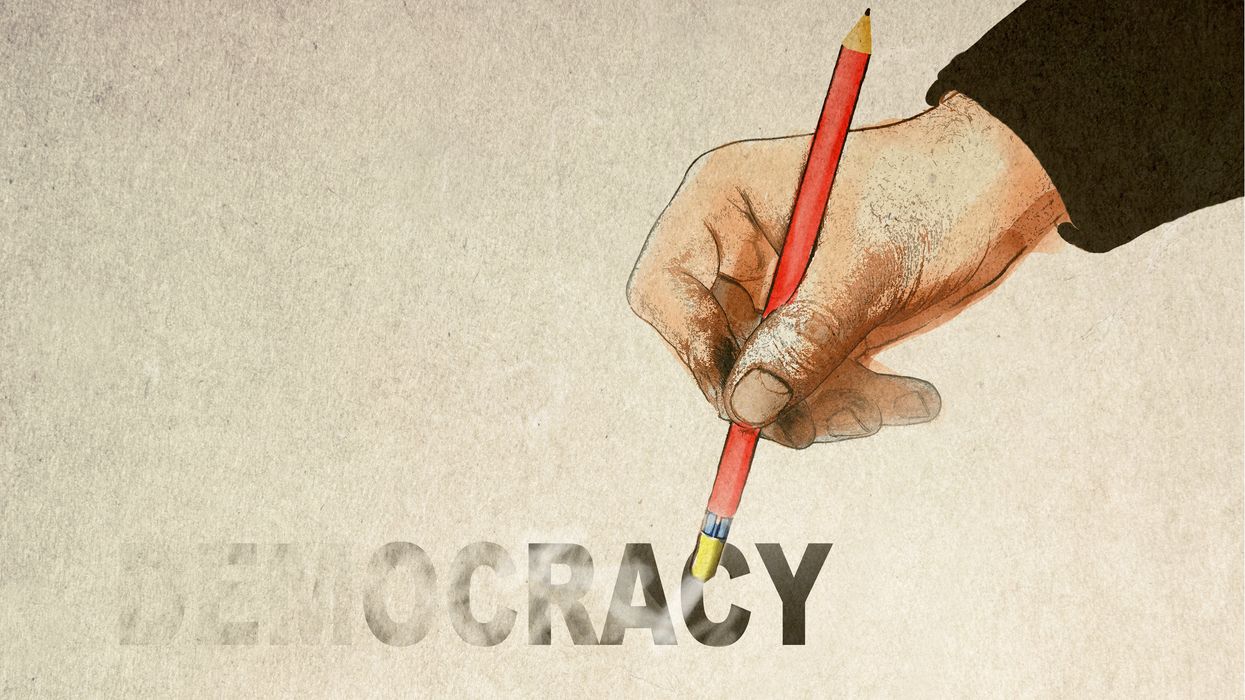

Still, the consequences of his view of presidential power and his revolution have been grave so far, leaving democracy and the rule of law in the United States staggering and some political leaders and citizens stunned that things they had long taken for granted could unravel so quickly.

But maybe, over the long term, what Trump is doing will work like an electric shock applied to a heart in cardiac arrest and jolt people out of their democratic slumber. This may sound odd. This is not something anyone would wish for.

As the lyrics from a 1960s rock song put it, “You don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone.”

That is one way of understanding why the rise of fascism in Europe turned out to be a boon for democracy, although no one knew it or could have foreseen it at the time. The incubation period for democracy’s century began on that tragic day, January 30, 1933.

The struggle against fascism and its unspeakable acts deepened democratic commitments here and around the world. Achieving a similar thing in our time will, hopefully, not require slaughter, war, and global catastrophe.

A crisis may be a terrible thing to waste but there is no guarantee that if we don’t waste it we come out better on the other side.

Just ask Woodrow Wilson.

Recall that, in 1917, President Wilson tried to rally support for America’s entrance into World War I by claiming that fighting the war was essential if the world were to “be made safe for democracy.” In his address to Congress asking for a Declaration of War, Wilson said, “Our object now, as then, is to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power and to set up among the really free and self-governed peoples of the world such a concert of purpose and of action as will henceforth ensure the observance of those principles.”

Going to war, “with this natural foe to liberty…[would require]…the whole force of the nation… We are glad…to fight thus for the ultimate peace of the world and for the liberation of…peoples… for the rights of nations great and small, and the privilege of men everywhere to choose their way of life…”

But, almost as soon as the war ended, Wilson‘s hopes for that lasting outcome were dashed. Instead, “the U.S. opted not to join the burgeoning League of Nations, even though it had been the nation to first propose such international cooperation. Instead, the United States focused on building the domestic economy by supporting business growth, encouraging industrial expansion, imposing tariffs on imported products, and limiting immigration.”

Three decades later, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt rallied the nation for war in Wilsonian language. The United States would be “fighting for the universal freedoms that all people possessed.”

FDR identified four such freedoms: freedom of speech, the freedom to worship in one’s own way, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

This time it worked. After the Second World War, there was no retreat.

At home, the fight against Hitler’s racist ideology helped propel the effort to make America’s democracy more democratic and inclusive. It deepened America’s appreciation of and attachment to democracy. This is registered by surveys that show that among people born in the 1930s, 75% of them say that it is “essential to live in a society governed democratically.”

Moreover, as Harvard University Professor Steven Levitsky said, “[T]here’s no question that after World War II…the United States, for decades, was a model to many aspiring Democrats and many democratic activists across the world.”

Since January 20, that is no longer the case.

The Washington Post observes that “as Trump upends democratic norms at home, his statements, policies, and actions are providing cover for a fresh chill on freedom of expression, democracy, the rule of law, and LGBTQ+ rights for autocrats around the world—some of whom are giving him credit.”

Professors Jason Brownlee and Kenny Miao note that since Trump came on the scene, we have witnessed what they call, “’a wave of autocratization’ threatening to engulf the world’s most venerable polities.” They point out that Trump returning to the Oval Office would mean “democracy is gone.”

What does this have to do with the possibility of a Trump-inspired democratic awakening?

My argument is this: In the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Communism, Americans began to take democracy for granted. They didn’t have to think about it. They didn’t have to be taught why it is valuable.

That is one reason young people are less attached to democracy than their parents or grandparents. They are not opposed to it; they just have not invested a lot in thinking about its preservation.

For them and all of us, the Trump Administration’s first days have been a reminder of democracy’s fragility and vulnerability. We can no longer assume that this country will always be a democracy or ignore the work that needs to be done to ensure that it will be.

Even as we come to this realization, it is important to pay attention to the lessons of history and the experiences of other countries. If we do, we will see that, to use Brownlee and Miao’s words, “the road from [democratic] backsliding to breakdown may be less traveled than previously assumed.”

“[N]orm erosion, institutional gridlock, and other woes, while certainly troubling—are not portents of dictatorship,” they wrote.

That is why Americans need to realize that we still have choices to make and those choices still matter. Our destiny is neither sealed nor guaranteed.

In fact, as Americans experience life under a government in which one person’s will is supreme, they may be inspired to stand up for democracy by Winston Churchill’s wisdom: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the rest.”

Austin Sarat is the William Nelson Cromwell professor of jurisprudence and political science at Amherst College.