As the election dust settles, one thing remains unchanged: many Americans are angry at and fearful of the "other side."

Just as before the election, many are hyper-focused on the extreme ideas and actions of their opponents. Democrats are shocked that so many could overlook Trump’s extreme behavior, as they see it: his high-conflict approach to leadership, his disrespect for democratic processes. Whereas Trump’s supporters see his win as evidence supporting the view that the left has grown increasingly extreme and out-of-touch.

But few see that our toxic divides are part of a self-reinforcing cycle —that the hostile, contemptuous behaviors of both political groups contribute to the very extremity on the “other side” that bothers them.

In major conflicts, it’s easy for people on both “sides” to believe it’s the “other side” that is the more extreme and unreasonable aggressor. How someone decides which group is worse will depend on how they filter the immense amount of information around us and how they prioritize its importance.

Let’s look first at demeaning, threatening behaviors on the left.

Before Trump was elected, liberals often painted him and his supporters in the worst possible light. Many influential people promoted the narrative that Trump support was primarily about bigotry, despite that view of things being simplistic and biased. Many minor and ambiguous statements by Trump have been interpreted in highly pessimistic and certain ways. There were many biased and irresponsible stories about the Trump/Russia story.

These approaches bolstered the narrative that Republicans were under attack by an establishment that treated them in biased and unfair ways. Such approaches helped give Republicans reasons for supporting aggressive and contemptuous responses (like the kinds that Trump engages in).

To be clear, this is not to blame political toxicity on Democrats, nor to let Republicans off the hook.

For one thing, Trump’s divisive personality can be seen as playing a role in making the left more angry and extreme.

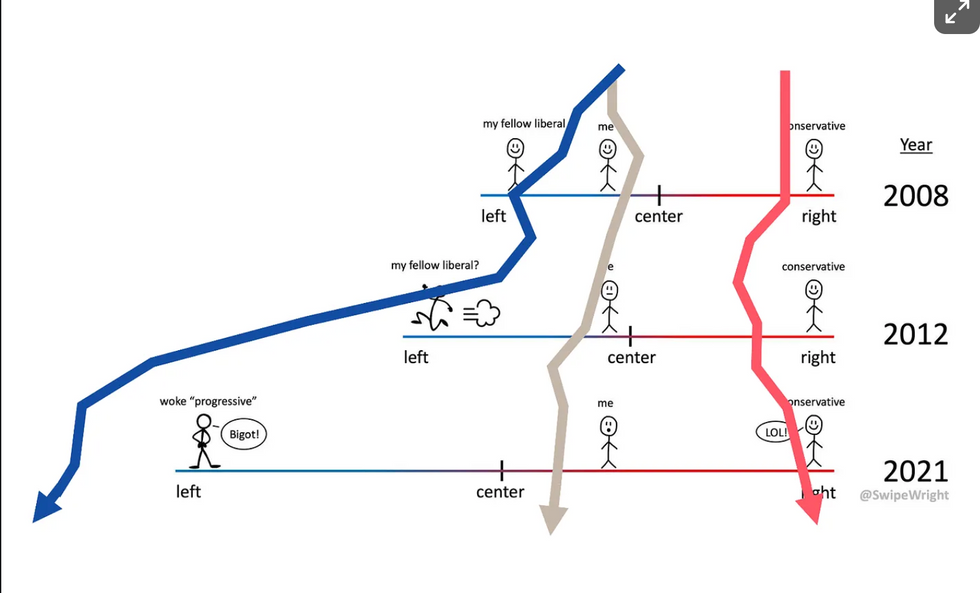

On the right, an oft-heard view is that the left has become significantly more extreme, while Republican-side stances have remained largely the same. (A popular meme by Colin Wright and shared by Elon Musk promoted this view.)

It’s true that some liberal-side stances have shifted rapidly. In the last few years, liberals became much more pro-immigration; their support of gender identity-related ideas increased quickly; anti-police views multiplied in 2020.

But what the focus on alleged liberal extremity misses is that groups in conflict are never symmetrical. What Trump and a Trump-dominated GOP contribute to our divides can’t be defined by political stances alone. Trump’s divisive nature—his promoting distrust of the legitimacy of elections, his frequent talk of “enemies” and retribution —those traits are perceived by many as dangerously extreme, but have little to do with issue stances or policy.

Trump is someone who has long been known for an aggressive, contemptuous style of leadership. (To learn more about that, I recommend Trumped!, a book about his Atlantic City days.) Trump has said several varieties of the idea that when someone hits him, he’ll hit back ten times as hard: that’s the very definition of someone who amplifies conflict.

And one can see this aspect of Trump even while being a Trump supporter. A gung-ho pro-Trump acquaintance told me he saw Trump’s personality as being like “gasoline on the fire” of our divides.

It’s easy to see how Trump’s aggressive rhetoric could shift some liberal stances. For example, his way of talking about immigration can help explain Democrats becoming more pro-immigration. Seeing him as cruel and aggressive on that issue would result in Democrats feeling more protective of immigrants.

It’s possible to debate Trump’s level of bigotry, but there’ve been many things he’s done that can understandably be perceived as bigoted. To name one example: the time he told four Democratic congresspeople to “go back and help fix” the countries they came from —even though only one of the four was born in a foreign country. He has associated with extreme people like Nick Fuentes, and has said that immigrants are “poisoning the blood” of America.

Trump’s personality and decisions, whether due to significant bigotry or not, have made it easier for people to believe the “racism explains his popularity” narrative. That view in turn increased demand among anti-Trump Americans for ideas that purported to find evidence of all the racism around us—racial equity and other antiracism-associated ideas—even as many of those ideas can easily be criticized as simplistic and divisive.

Trump’s aggressive personality has created a lot of dislike (even among those with similar views). And when we dislike people, we find ourselves wanting to be unlike them. Another possible example of this dynamic playing out: After Trump’s 2016 win, the Democratic Socialists of America reported a big upswing in membership.

As journalist Damon Linker has argued, Trump’s election resulted in Democrats “staking out positions understood to be the diametric opposite of Trump’s stated stance.” (An important word there is “understood,” as it’s common for us to have distorted, overly pessimistic perceptions of our opponents.)

Pro-Trump Republicans should be willing to consider that Trump’s contemptuous manner has been a factor in making liberal-side beliefs more extreme. And Democrats should be willing to examine how liberal-side contempt has led to making Republicans more extreme.

Of course this isn’t the only factor that explains changes in stances or in partisan hostility over the last several decades. There are many more factors ( social media, for one)—but it’s a piece of the puzzle more of us should consider. When we see how intertwined and connected our political groups are, it helps us see that contemptuous approaches don’t just amplify conflict; they’re self-defeating.

If we want to avoid worst-case scenarios in America and build a brighter future, we’ll need more people to think about the role they play in amplifying toxicity. We’ll need more people to see that it’s in their own best interest—and the country’s—to work towards their political goals while avoiding demeaning those on the “other side.” We’ll need more people to push back on divisive approaches among their political peers and allies.

This isn’t easy. Many forces, both internal and external, push us toward more conflict and provocations. But leaders bold enough to inspire us to transcend toxicity may one day be celebrated as true American heroes in the history books.

Zachary Elwood is the author of “Defusing American Anger” and the host of the psychology podcast People Who Read People.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift