Shino is an assistant professor of political science at the University of North Florida. Smith is a professor and chair of political science at the University of Florida.

When eligible citizens register to vote, it doesn't necessarily mean that they will turn out.

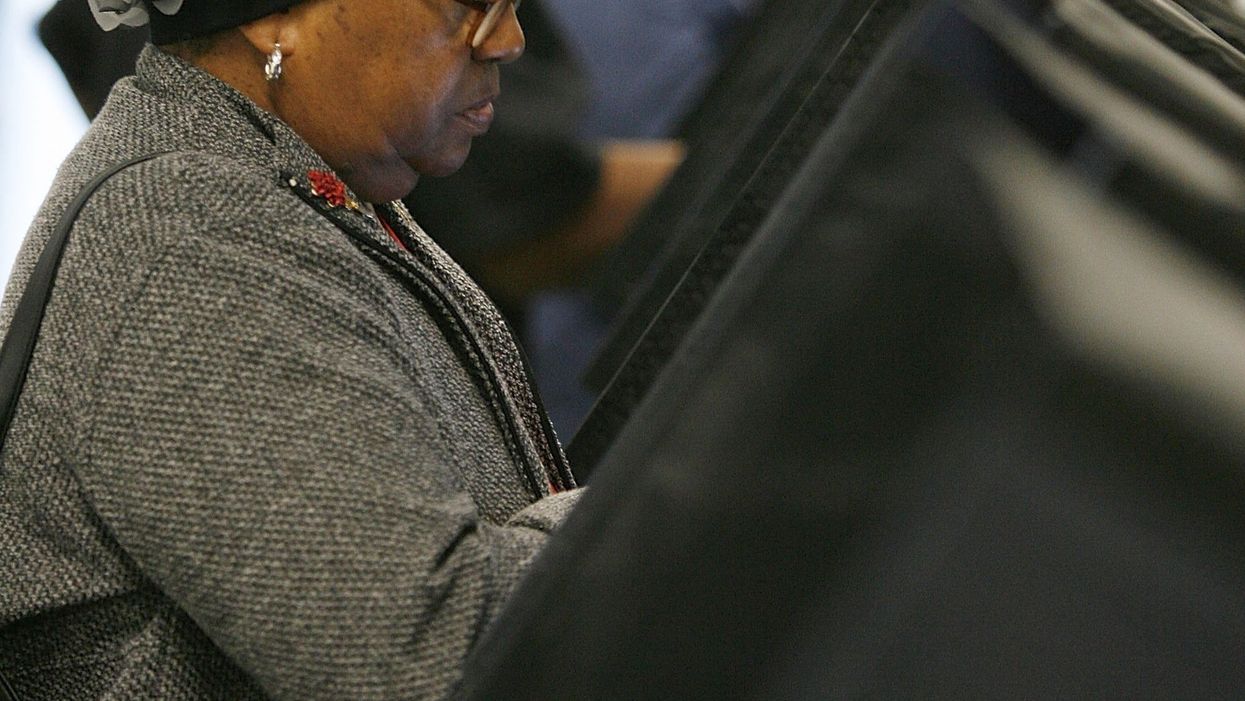

Voting in the United States is a two-step process. Citizens in every state except North Dakota must first register before casting a ballot.

As we discuss in our article in Electoral Studies, the timing of when a voter registers to vote affects whether they vote in the upcoming election. It also relates to whether they become a repeat voter, or what political scientists refer to as a "habitual voter."

Our findings could have an impact on turnout this November and in future elections.

In Canada, Germany and many other countries, voter registration is automatic. Not so in this country.

But there have been efforts during the last 25 years to make voter registration easier in the United States.

Since 1993, with the enactment of the National Voter Registration Act, all U.S. citizens can register to vote when they apply for a driver's license or services at other governmental agencies. Citizens in 37 states are also able to register to vote online, making the process even more convenient.

More recently, more than a dozen states have enacted legislation changing voter registration at DMV offices from "opt-in" to "opt-out." When applying for or renewing a driver's license, you are automatically registered to vote unless you choose not to. Initial research on this approach from Oregon suggests that people who are automatically registered, compared to those already registered, were much younger and geographically reside in areas with a racially diverse population, lower income and lower education levels.

Of course, eligible citizens fall through the gaps. That's where voter registration groups come in, fanning across the country, pen and paper (or smartphones) in hand, to register new voters.

As a final measure to encourage voting, citizens in 21 states and the District of Columbia may register at the polls on Election Day. Many eligible citizens, however, reside in a state in which they must register at least 29 days before Election Day.

But registration doesn't equal voting. Not everyone who successfully registers prior to Election Day actually goes to the polls, especially in midterm elections.

In our study, drawing on nearly a decade of voting data in Florida, we find that when voters register affects their voting behavior.

Individuals who register in the waning months prior to Florida's 29-day registration cutoff are more likely to vote in the upcoming election than others who register throughout the previous election cycle.

However, these last-minute registrants are less likely to vote in future elections. The act of registering to vote, and even voting in the next election, does not translate into becoming a repeat, regular voter. We think this is because those who register close to the deadline may be mobilized to do so by campaign events tied to the upcoming election, but they may not become regular voters for the long haul.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Click here to read the original article.

![]()