Wolk is executive director of the Equal Vote Coalition, which promotes the adoption of the alternative election method known as STAR voting.

This self-fulfilling prophecy puts the power of American politics soundly in the hands of those who get to decide who is "electable." The result is a political landscape owned by the big-money donors and corporate media. (Spoiler alert: The candidate who is deemed the most "electable" is almost always the one who's raised the most money.)

But why does this electability narrative have so much power? Some people do vote their conscience, but the data on the subject is crystal clear: Many voters simply don't.

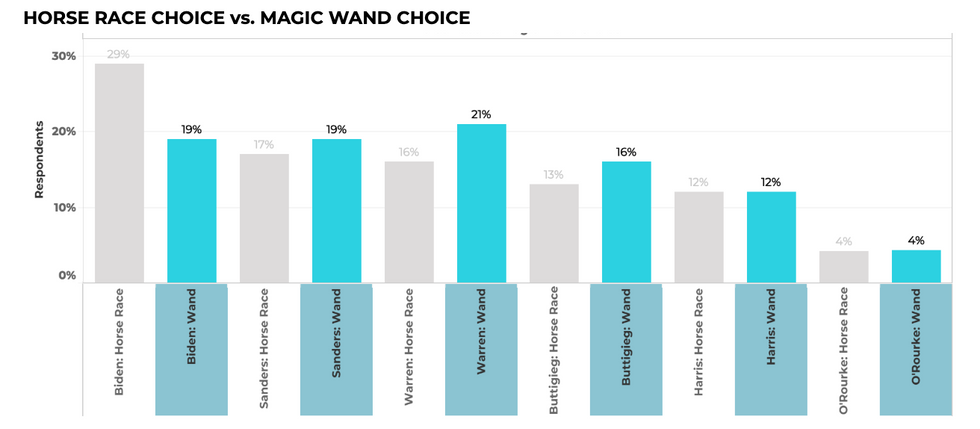

In a recent poll, voters were asked two questions: Who would they vote for if the primary was that day, and who would they pick if they had a magic wand? The difference was stunning. In the real world strategic voting question, Joe Biden was in first place leading Bernie Sanders by a full 12 percent. In contrast, when voters were free to pick their candidates honestly Biden and Sanders were actually tied for second place, 2 percentage points behind Elizabeth Warren.

Why do so many vote for a candidate who's not their favorite? Whether or not they realize it, strategic voters perform evasive maneuvers for good reason. When voters can only vote for one candidate and are unable to show preference order and degree of support, elections often fall victim to the "spoiler effect." That's the very real phenomenon where an unpopular and polarizing candidate wins, even though a majority would have preferred any number of others.

Avalanche Strategy

Avalanche Strategy

To reform advocates and political scientists this is nothing new. Experts are in consensus that our system is the worst way to conduct elections with more than two candidates. (It's called the two-party system because it only works with two candidates in a race.)

The good news is that this catastrophic problem is a relatively easy fix with a more expressive ballot. The solution is STAR voting.

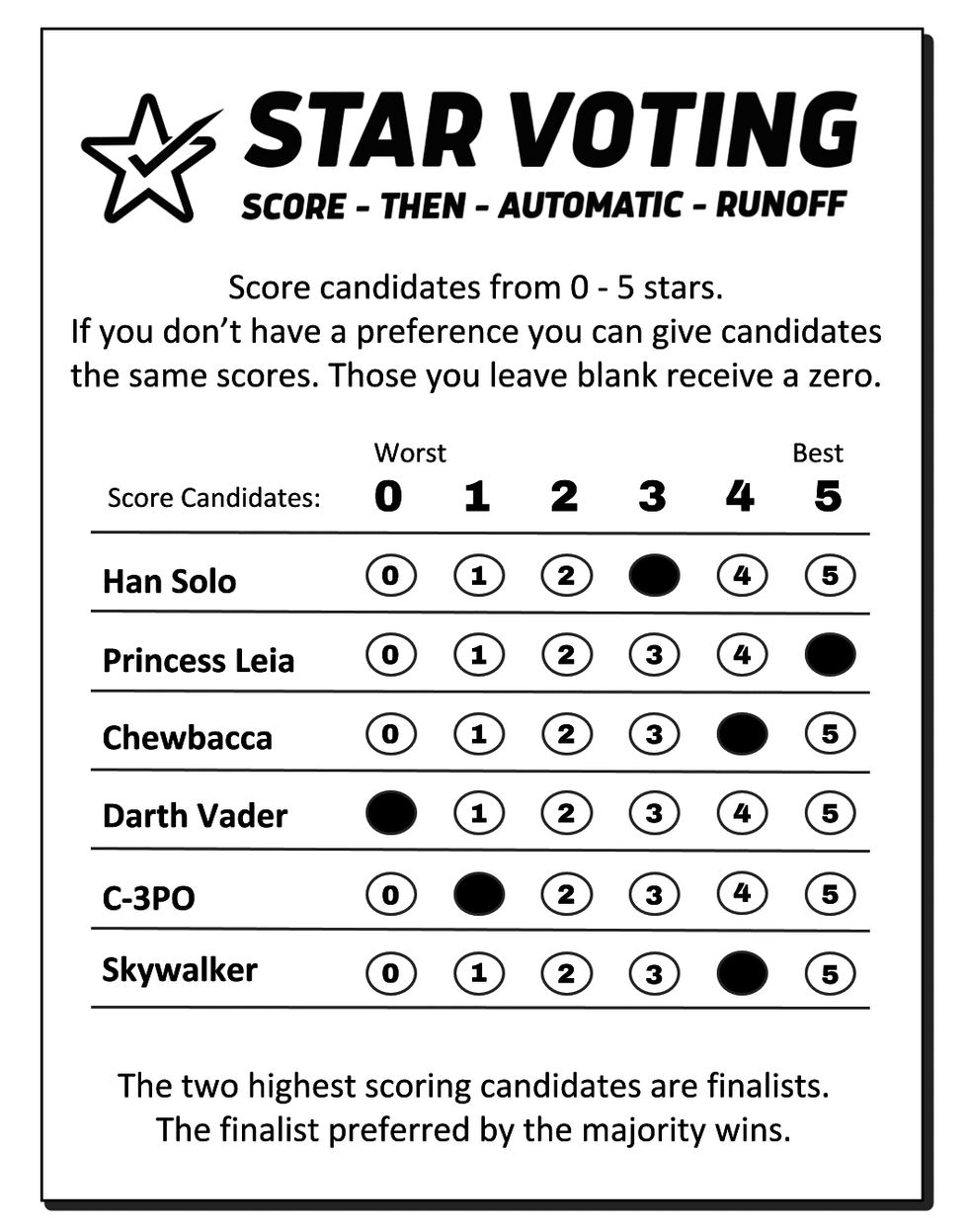

The acronym STAR stands for Score, Then Automatic Runoff. And that's exactly how it works. You score candidates from zero up to 5. The two highest scoring candidates advance, and the finalist preferred by the majority wins.

In this system, your full vote always goes to the finalist you prefer. So even if your favorite can't win, it's safe to vote your conscience. STAR eliminates vote-splitting and the spoiler effect so there's no need to be strategic. If your favorite can't win, your vote automatically goes to the finalist you prefer.

And, like a primary and a general election all in one, voters only need to vote once in November for nonpartisan races. The bonus: Skipping low-turnout primaries leads to more representative elections and saves money.

It's an elegant solution to an age old problem which takes it one step further than older reforms like ranked-choice voting. Also known as instant runoff, ranked-choice has had some major successes, but despite being much better than traditional choose-one voting, reform efforts have frequently resulted in partisan stalemates, major logistical and security issues — and repeals.

First, it doesn't solve the problem of vote splitting. RCV only eliminates the spoiler effect in races with two viable candidates. If there are three or more, the system can ignore voters preferences and fail to elect the one preferred over all others. In RCV not all rankings are counted, and depending on the order of elimination it's possible for your vote to actually backfire, helping to elect your least favorite candidate. The more candidates, the more likely this is to happen.

Second, RCV requires significant investment to implement, presents chain-of-custody issues because of the centralized tabulation needed, and isn't compatible with the latest in auditing protocols.

Third, RCV produces exhausted ballots and can waste votes. While it's usually summarized as, "If your first choice is eliminated your next choice will be counted," there is a devil in the details. That's only true if your other candidates remain in the running. Some voters will see their first choice eliminated and the others on their ballots ignored, putting their voices at serious disadvantage. Voters who prefer a strong underdog are the most likely to have their ballot "exhausted," which means that even though that voter had a preference among the finalists, their ballot was not counted in the deciding round.

Invented in 1870, RCV's multiple round process is overcomplicated, runs into constitutionality issues in some states and physically leaves some ballots in the discard pile.

For these reasons election scientists went to work. STAR voting was invented to address these concerns. The result was an upgrade that still delivers on the goals of the voting reform movement, while addressing the valid concerns with the previous proposal.

Equal Vote Coalition

Equal Vote Coalition