We do not want bloodshed. Not in Gaza. Not in Ukraine. Not in another American school or home. The thought of hostages, children trapped under rubble, and screams amid gunfire pains us deeply. We say violence is wrong, period, and we demand that the government do something about it—that is, until it’s wrapped in plastic at a grocery store.

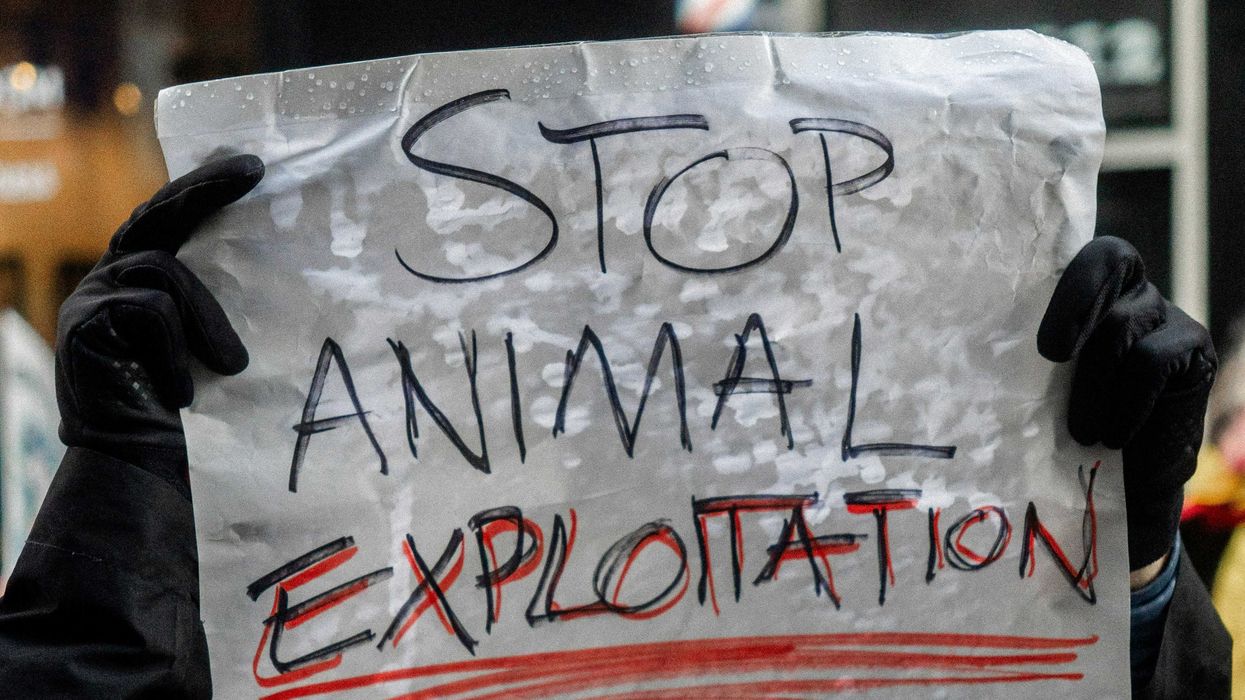

Every day, in places most of us will never see, workers kill animals. These victims haven’t done anything wrong; they are simply born in bodies that humans decide do not matter. We know what happens to them behind slaughterhouse doors—even if we try not to think about it.

Our government is more than complicit in this violence—it is an active participant, spending billions of dollars on animal agriculture, with some farms receiving tens of millions each year. Farmers who grow fruits, vegetables, and grains receive far less. That is why PETA is calling on lawmakers to end these wasteful subsidies and redirect the money to vegan foods, helping grocers stock healthy animal-free foods and ensuring everyone has access to compassionate, sustainable options.

The U.S. government also enables abuse in these industries to continue: PETA has documented that federal inspectors routinely record animals suffering in clearly illegal ways at slaughterhouses—animals punched, shot multiple times, left conscious as they are hoisted and hacked apart—yet the agency has never once referred these cases for federal prosecution. With lax inspections, weak enforcement, and confusing signals about whether state and local anti-cruelty laws can be applied, offenders go unpunished, cruelty continues to go unchecked, and offenders are emboldened because there are no consequences for their actions. This lack of enforcement sends a dangerous message: that cruelty to animals used for food is protected by the very system meant to stop it.

A healthy society depends on its members to question violence in all its forms, whether inflicted by nations or corporations, with missiles or in slaughterhouses. So let’s think about it: You would not eat a dog, so why eat a chicken? Dogs and chickens have the same capacity to feel pain, but prejudice based on species allows us to consider one animal a companion and another as food.

A paper published in the Social Psychological Bulletin revealed the mental gymnastics that some meat-eaters engage in to cope with their uncomfortable cognitive dissonance. The review examined self-soothing strategies people use to respond to triggers—things that recall the contradiction of eating meat while supposedly caring about animals. Processed “products” help numb that truth—when flesh is ground, shaped, and renamed, compassion and disgust are easier to suppress. Language itself softens the blow: “Steak” sounds more palatable than “dead sentient being.”

To ease our conscience, companies slap “humane” and “animal welfare certified” labels on animal-derived foods—but PETA’s investigations have revealed that these labels are meaningless and misleading. At Sweet Stem Farm, formerly a Whole Foods supplier, PETA found pigs crammed into sheds, denied outdoor access, suffering from untreated injuries like bloody rectal prolapses and enduring painful deaths, all while being marketed as “happy meat.” And at Plainville Farms, a PETA investigator witnessed workers violently abusing turkeys—they kicked, stomped, choked, and even mocked them with sexual gestures—while sick and injured birds were left to suffer and die.

Some of us may also deny that animals feel pain or comprehend what’s happening to them. But they do. Take fish, for example: A new study in Scientific Reports reveals that fish experience severe pain—and can suffer for at least 10 agonizing minutes after being pulled from the water.

This compartmentalization—the capacity to care selectively—is not just a personal moral contradiction. It’s a collective psychological barrier that enables societies to justify all kinds of cruelty: war, exploitation, and violence. When we decide that some lives matter less, empathy diminishes. And when empathy diminishes, democracy itself becomes fragile.

As the late, great Helen Thomas said: “A healthy democracy requires an informed people, facts make a country safe, and facts protect people.” The fact is that across the U.S., 99% of animals used for food spend their entire lives on farms—never enjoying sunlight, fresh air or freedom until they’re packed onto trucks bound for slaughter.

Vegan living is a vote for a world in which compassion is not rationed by species or convenience. Just imagine schools teaching that kindness should extend to every living being while feeding students a healthy plant-powered lunch. Imagine governments investing in food systems that don’t involve raising animals in squalor just to kill them while destroying the planet. If we can imagine it, we can do it. Everything starts with an idea.

The path to peace will never be paved with selective empathy. All it will take is for people like you and me to shift to vegan foods. It’s easy. Simple actions like choosing a lentil stew over processed flesh or ordering oat milk in your latte—these can shape markets and public norms. And it starts with us.

Rebecca Libauskas is a writer for the PETA Foundation, www.PETA.org.