In September, I wrote, “No matter who wins, the next president will declare that they have a ‘mandate’ to do something. And they will be wrong.”

I was wrong in one sense.

Now, I still think the idea of mandates are always conceptually flawed and often ridiculous. The only relevant constitutional mandate Donald Trump enjoys is the mandate to be sworn in as president.

Think about this way: Trump’s coalition together contains factions that disagree with one another on many things. Assume that self-described Republicans are Trump voters. According to the exit polls, about a third (29 percent) of voters who support legal abortion voted for Trump, while 91 percent of those who think it should be illegal voted for him. There are similar divides over support for Israel, mass deportation of immigrants and other issues. Heck, 12 percent of voters who think his views are “too extreme” nonetheless voted for him. Five percent of the people who would feel “concerned or scared” if he were elected still backed him at the polls.

In short, whatever Trump believes his mandate is, at least some of the people who voted for him will have different ideas. Save for dealing with inflation and righting the economy, there’s very little that he can do that won’t result in some people saying, “This isn’t what I voted for.” (Even if you believe in mandates, how big could Trump’s be given it’s tied as the 44th-best showing ever in the electoral college?)

None of this is unique to Trump. Presidential electoral coalitions always have internal contradictions. FDR had everyone from progressive Blacks and Jews to Dixiecrats and Klansmen in his column.

Many people seem to think that politics is what happens during elections. But politics never stops. Once elected, the venue for politics changes. Presidents believe, understandably, that they were elected to do what they campaigned on. The challenge is that Congress and state governments are full of people who won an election too. And they often have their own ideas about what their “mandate” is. Postelection politics is about dealing with that reality.

Which gets me to what I got wrong. Although voters generally may not have spoken with anything like one voice on various policies, Republican voters voted for Republicans who would be loyal to, and supportive, of Trump. In other words, whether it fits some political scientist’s definition of a mandate, Republican senators and representatives believe that they have a mandate to back Trump.

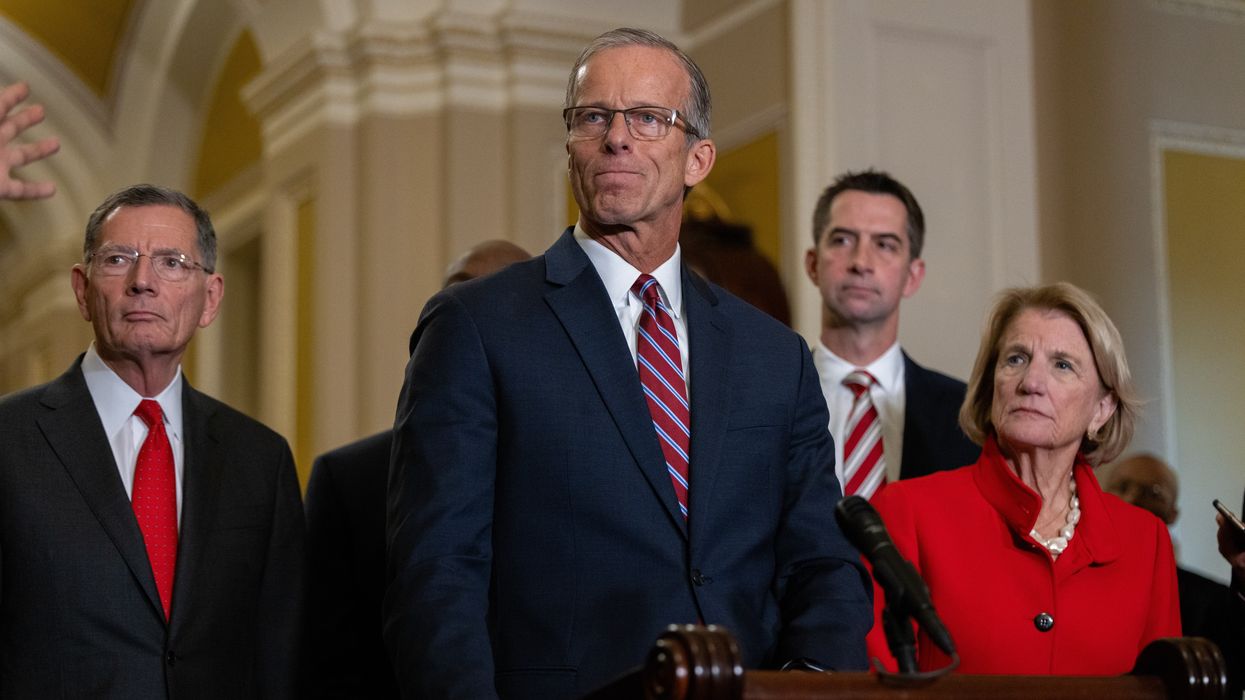

The jockeying to replace Mitch McConnell as majority leader in the next Senate makes this so clear, it’s not even subtext, it’s just text. The three Republican contenders, John Thune of South Dakota, John Cornyn of Texas, and Rick Scott of Florida, fell over each other to reassure Trump and everyone else that they will do everything possible to confirm Trump’s appointees with breakneck speed.

Thune, who won the job last week, said in a statement, “One thing is clear: We must act quickly and decisively to get the president’s cabinet and other nominees in place as soon as possible to start delivering on the mandate we’ve been sent to execute, and all options are on the table to make that happen, including recess appointments.”

Thune was playing catch-up to Scott, who’d already signaled that he’d be Trump’s loyal vassal in the Senate. This earned him the support of Elon Musk and other backers who want Trump to be as unrestrained as possible.

An honorable and serious man of institutionalist instincts, Thune is simply dealing with the political reality of today’s GOP. The argument that anyone inside the Republican Party should do anything other than “let Trump be Trump” is over, at least in public.

Given that only 43 percent of voters said Trump has the moral character to be president (16 percent of his own voters said he doesn’t), this could lead to some challenging political choices for the party.

Once again, a victorious party is sticking its head in the mandate trap. In the 21st century, Yuval Levin writes, presidents “win elections because their opponents were unpopular, and then — imagining the public has endorsed their party activists’ agenda — they use the power of their office to make themselves unpopular.” This is why the incumbent party lost for the third time in a row in 2024, a feat not seen since the 19th century.

Hence the irony of the mandate trap. In theory, Trump could solidify and build on his winning coalition, but that would require disappointing the people insisting he has a mandate to do whatever he wants. Which is why it’s unlikely to happen.

Jonah Goldberg is editor-in-chief of The Dispatch and the host of The Remnant podcast. His Twitter handle is @JonahDispatch.

©2024 Tribune Content Agency, LLC.