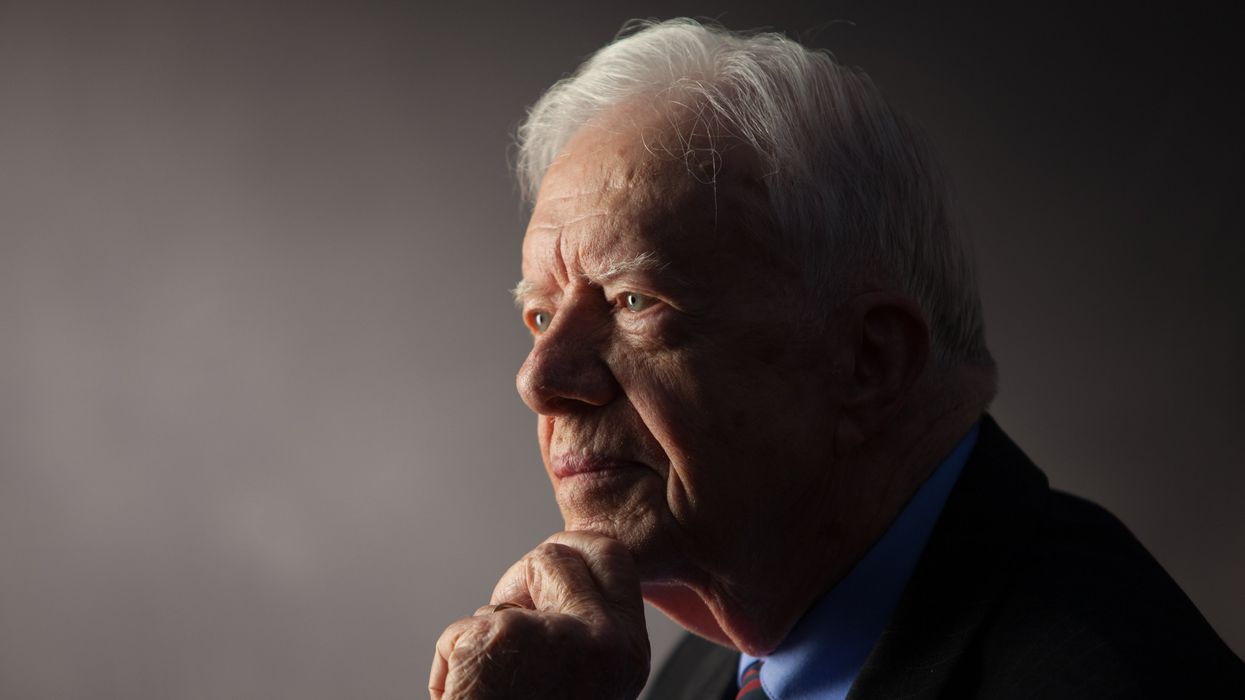

President Jimmy Carter touched the lives of millions, in countries around the world, through contact points as diverse as public health campaigns, Sunday school lessons, rural homebuilding, or appreciation of southern rock. Included in his huge roster of impact is the organization I lead, Election Reformers Network, which was founded by international democracy experts inspired by his leadership. Like many others, I had the good fortune to work with President Carter on election missions overseas and to support The Carter Center’s expansion of its work into the United States. Carter’s legacy has much to teach democracy reformers here in the U.S.

President Carter learned early in his career about the anti-democratic forces he would challenge so often throughout his life. He lost his first election for Georgia state senate because of election fraud so blatant that “ the dead voted alphabetically.” Georgia had long been a one-party state ruled by insiders and local Democratic Party bosses. Blacks were systematically disenfranchised, and voting rules gave rural counties vastly disproportionate power through an in-state version of the electoral college.

Carter fought in court and in the media against the party operatives and their ballot stuffing, and he was finally awarded his senate seat. Along the way, many counseled him to give up and accept the way things worked, but he persisted. His commitment to the principles of fairness mobilized key advocates to challenge the status quo. But that same moral grounding meant his victory wasn’t laced with vindication. In his book about the election, Carter is remarkably even-handed toward the system that had tried to cheat him.

Carter’s win launched his political career and helped make democracy and election fairness central to his work in the White House and beyond. In 1982, the year he launched The Carter Center, only a third of the countries of the world were electoral democracies ( according to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance), and a peaceful democratic transfer of power seemed impossible across most of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Central and Eastern Europe. Many assumed that democracy couldn’t take root in certain regions or cultures. But before the end of the century, the number of electoral democracies had more than doubled, burying those old doubts about cultural barriers.

President Carter and The Carter Center played an important role in this huge increase in genuine elections and human freedom around the world. Carter’s work overseas often resembled his seminal Georgia senate win. He persisted in the face of daunting obstacles and kept long-term goals in sight. His faith in the betterment of all people made every corner of the globe important to him. In his many election monitoring missions, he emphasized the transparency that deters fraud and ensures fair elections. But Carter also focused on the important underlying structures of democracy, which so often favor insiders and incumbents, including who runs elections and how votes translate into power.

There are many lessons here for US reformers, including the importance of both elections and the wider range of rules and institutions that make democracy function. His successes overseas depended on authentic nonpartisanship that we can learn from, a complete neutrality toward election outcomes. For me personally, more specific lessons include his advocacy for the U.S. to move away from relying on partisan insiders to run elections, a cause Election Reformers Network has long supported. His opposition to electoral-college-style voting in Georgia reconfirms my concern about the many distortions of our presidential voting system and the need, long though it will take, for constitutional reform.

But Carter’s most important lessons are moral. He was able to combine an almost spiritual commitment to full and fair democracy with respect and empathy toward even those who oppose democratic change. Often, the key to his success was a willingness to personally connect with and trust actors whom most would assume to be his adversaries. “He built trust with autocratic leaders under threat from opposition movements in countries such as Nicaragua and Zambia,” remembers Democracy International CEO Eric Bjornlund, who worked with President Carter in several countries over more than a decade. “That quality helped him succeed in ushering in peaceful transitions in those pivotal countries.”

These considerations bring up questions about approaches to the very different man who, in a few short weeks, will occupy the White House. Carter voiced opposition to Trump policies, but personally attended his first inauguration in 2017. In a 2022 New York Times opinion piece, Carter spoke out against the “lies” and “disinformation” “that stoke distrust in our electoral system.” He would surely be concerned now by Trump’s continued refusal to accept the verdict of the rule of law regarding the 2020 elections. Despite these very real concerns, Carter would be at Trump’s next inauguration on January 20 if he could.

Democracy is grounded in the rule of law and in respect for all people. How fortunate we are to have President Carter’s example of deep moral commitment to both goals.Johnson is the executive director of the Election Reformers Network, a national nonpartisan organization advancing common-sense reforms to protect elections from polarization.