FT HUACHUCA, Ariz. - Inside a windowless and dark shipping container turned into a high-tech surveillance command center, two analysts peered at their own set of six screens that showed data coming in from an MQ-9 Predator B drone. Both were looking for two adults and a child who had crossed the U.S.-Mexico border and had fled when a Border Patrol agent approached in a truck.

Inside the drone hangar on the other side of the Fort Huachuca base sat another former shipping container, this one occupied by a drone pilot and a camera operator who pivoted the drone's camera to scan nine square miles of shrubs and saguaros for the migrants. Like the command center, the onetime shipping container was dark, lit only by the glow of the computer screens.

The hunt for the three migrants embodied how advanced technology has become a vital part of the Trump administration's efforts to secure the southern border. This type of drone, previously used in warfare, is operated by the National Air Security Operations division of U.S. Customs and Border Protection at the Army base about 70 miles south of Tucson. A reporter was allowed to observe the operation in April on the condition that personnel not be named and that no photographs be taken.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security allocated 12,000 hours of MQ-9 drone flight time this year at the Fort Huachuca base, and states that the flights cost $3,800 per hour. However, a 2015 inspector general report estimated the cost to be closer to $13,000, factoring in personnel salaries and operational costs. Maintenance issues and bad weather often mean the drones fly around half the allotted hours, officials said.

An MQ-9 Predator B drone prepares for takeoff at the National Air Security Operations Center in Sierra Vista, Arizona. Photo by Steve Fisher/Puente News Collaborative

With the precipitous drop in migrant crossings at the southern U.S. border, the drones are now tasked with fewer missions. That means they have the time to track small groups or even individual border jumpers trekking north through the desert, including a father and child.

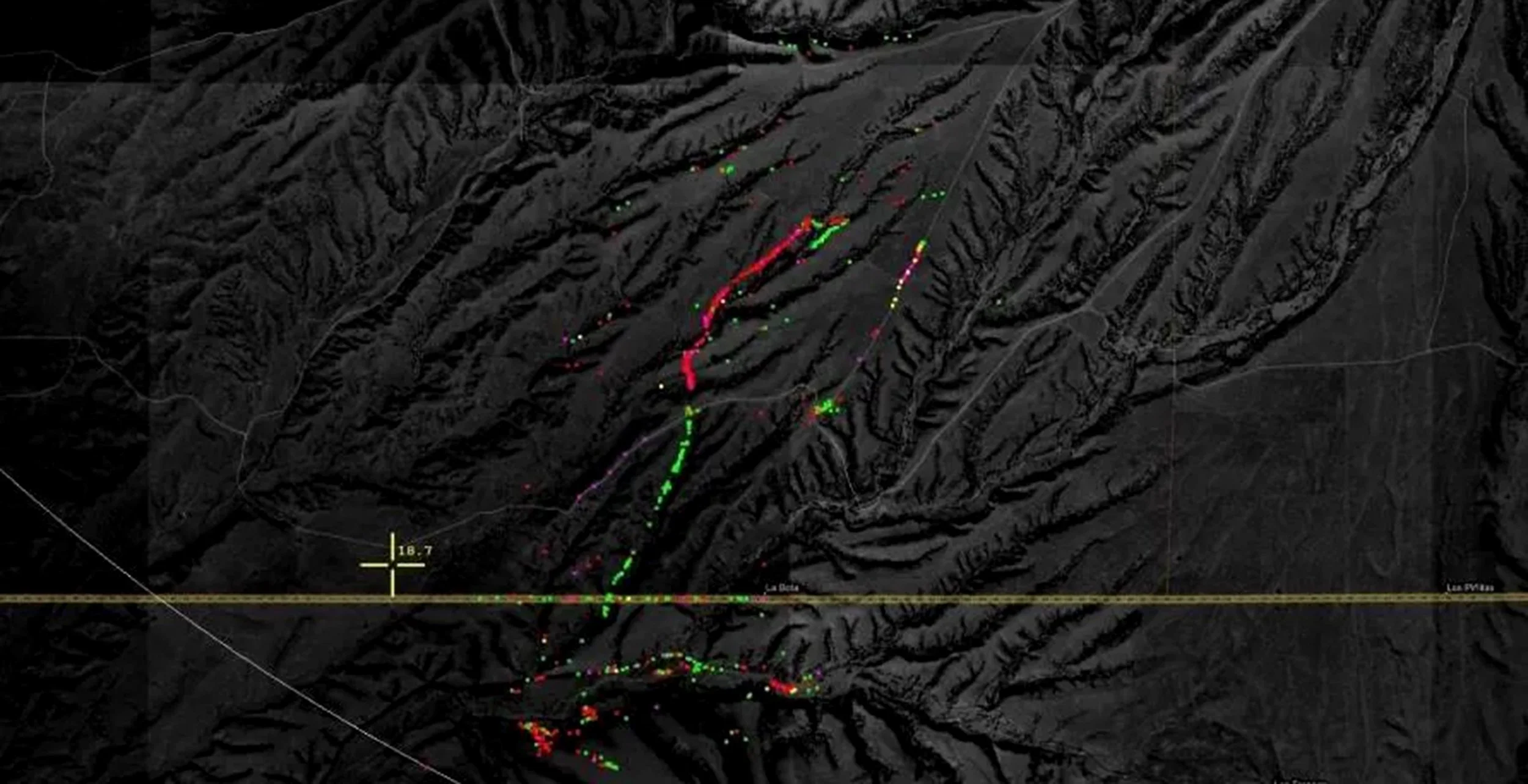

The drone flying this day was mounted with radar, called Vehicle and Dismount Exploitation Radar, or VaDER, that could identify any moving object in the drone’s sight, and pinpoint them with color-coded dots for the two analysts in the first container. The program had already located three Border Patrol agents, one on foot and two on motorcycles, searching for the migrants. The analysts had also identified three cows and two horses, headed towards Mexico.

Then, one of the analysts spotted something.

“We got them,” he said to his colleague, who had been scanning the terrain. “Good work.”

The analyst dropped a pin on the migrants, and the VaDER program began tracking their movement in a blue trail. Now, he had to guide agents on the ground to them.

“We've got an adult male and a child, I think, tucked in this bush,” the analyst radioed to his team, as he toggled between the live video to an infrared camera view that shows the heat signature of every living thing in range. The analyst saw his Border Patrol colleagues approaching on motorcycles.

The roar of the oncoming machines scared up a bird, the tracking program showed. The migrants began running.

“OK, it looks like they're starting,” the camera operator radioed to the Border Patrol agents. “They’re hearing the bikes. They hear you guys.” The camera operator and the other personnel spoke in the professional, matter-of-fact tone of 911 operators.

One adult and the child began scrambling up a hill. “They’re moving north and west, mainly,” the camera operator said. “Starting to pick up the pace going uphill.”

VaDER GMTI imagery output from a CBP MQ-9. Image courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection

The agents rushed in on the pair and detained them. It was a mother and her child. The drone team turned its attention to the third person, who was stumbling through the brush and making a beeline for the Mexican border.

“If you cut due south from your current location,” the drone pilot said to the camera operator. “You should pick up some sign.”

The camera operator, as directed, panned across the desert, scanning farther and farther south.

“I’ve got them,” he said when he spotted someone running. He radioed the coordinates to the Border Patrol team. By now, the man, carrying a backpack, had scaled a hill.

“He’s on the ridge line right now, working his way up due south, slowly,” the camera operator radioed.

Then the man dropped something.

“Hey, mark that spot,” the camera operator said. “He just threw a pack, right here where my crosshairs are at.”

Agents would go back later and see if the backpack contained drugs, an analyst said. “Usually, if it’s food or water, they’re not going to do that,” he said.

On this spring morning, the drone wasn't the only airborne asset deployed. A helicopter had joined the chase to catch the southbound man, who stumbled, got up, and kept running.

“He took a pretty good spill there,” an analyst said into the radio.

“We have help inbound, three point five minutes out,” the camera operator said.

A helicopter came into the drone’s view. It swooped in, circling the location of the man, who was by now hiding under a bush.

“You just passed over him,” the camera operator radioed the helicopter pilot. “He’s between you and that saguaro.”

With a keystroke, he switched to infrared vision to find the man’s heat profile through the brush to make sure he still had him.

Guided by the camera operator, the pilot landed the helicopter in a cloud of dust near the cowering target. The video feed showed agents jump out of the aircraft, detain the man, and load him into the helicopter. The chopper lifted off and tilted back north towards a nearby Border Patrol post.

“Thanks, sir, appreciate all the help,” the analyst said to the helicopter pilot.

Mission accomplished, the drone pilot turned the MQ-9 back along the U.S.-Mexico border, scanning the vast desert in search of more migrants. The military is planning to deliver a third MQ-9 drone to the base this fall after spending a year retrofitting it for civilian authority use.

MQ-9 Predator Drones Hunt Migrants at the Border was first published by palabra and republished with permission.

Steve Fisher is a Puente News Collaborative correspondent, covering security issues in Mexico.

This article was edited by Steve Padilla, Column One Editor for the Los Angeles Times.