The most important legal challenge in decades to a basic tenet of open government — laws should be available to public to read for free — went before the Supreme Court on Monday.

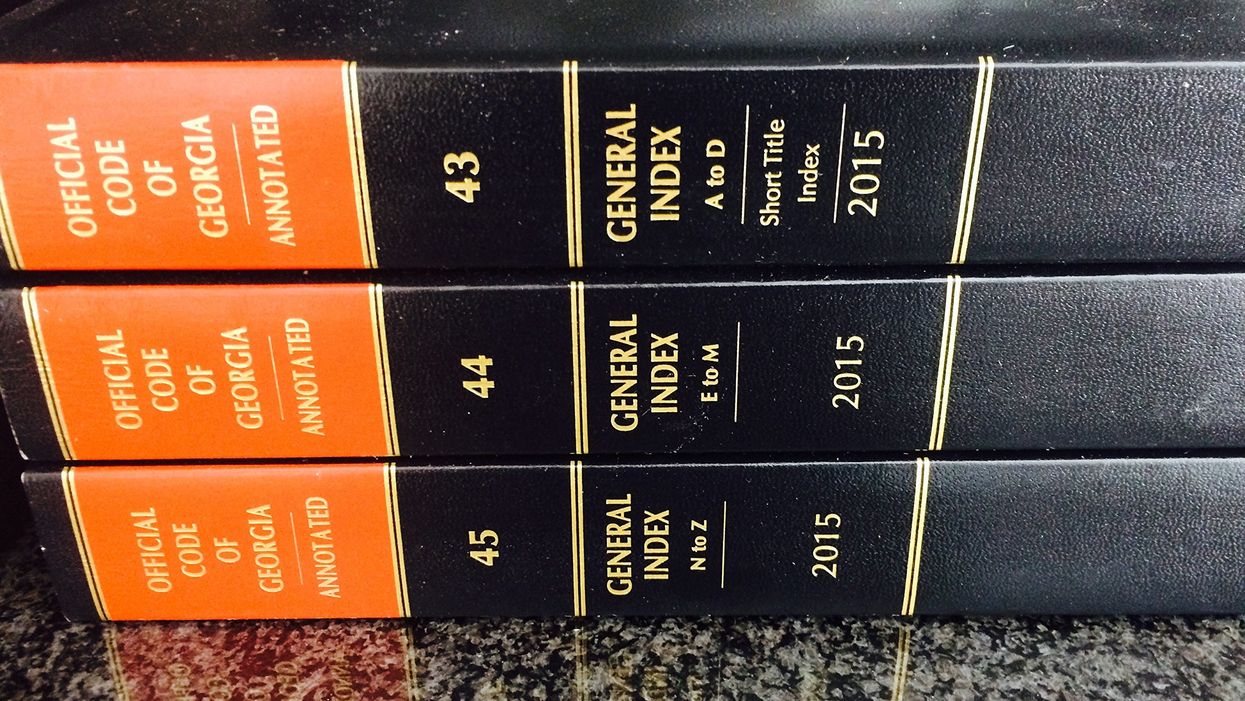

The justices heard arguments in a dispute over whether Georgia may have copyright protections on its annotated legal code books, which means they're not available to the public without cost. It appears to be the first time in more than a century the court has considered the limits of the "government edicts doctrine," which bars copyrights on statutes and legal decisions.

Open records proponents, civil rights groups and the news media say it's unconstitutional to limit the peoples' access to the law books most widely in use. The Trump administration has taken Georgia's side.

The fight is not over the actual statutes enacted by the General Assembly, which everybody agrees may not be subject to copyright protection. The dispute is over the annotated code, where the texts are accompanied by detailed explanations of legislative history and references to relevant court precedents. These are the essential reference books that lawyers, judges, lawmakers and citizens use every day to understand the meaning of the laws.

The case began when Georgia sued a public record activist, Carl Malamud, to force him to stop publishing the annotated code on his website, public.resource.org.

"If a democracy is based on an informed citizenry and ignorance of the law is no excuse, how can we possibly justify requiring citizens to obtain a license and pay a tax before they read the law and repeat it to their fellow citizens?" he replied.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in his favor last year, saying: "Because they are the authors, the people are the owners of these works, meaning that the works are intrinsically public domain material and, therefore, uncopyrightable."

But Georgia sees it differently, especially because the annotated law books are ultimately published by a private contractor, LexisNexis, and part of the company's deal with the state is that it gets to cover its production costs and make some profit by attaching a copyright and selling the volumes for $404.

And while the annotation process is overseen by a government commission, the decisions are made by the contractor. And the annotations — commentaries, case references and editor's insights — are not themselves the law.

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia have asked the court to take Georgia's side, on the grounds that without a profit motive and copyright shield no publishers will want to produce the law books.

Those who have filed briefs on the other side include the American Library Association, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Intellectual Property Association and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, which was joined by Gannett Co., the Los Angeles Times and The New York Times.

"If the First Amendment requires public access to criminal trials so that citizens may oversee and participate in government, then citizens must also have access to the laws that organize their society (and that form the basis of those criminal trials)," the media organizations said.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift