Vanderklipp is a senior fellow at the Election Reformers Network.

Only hours after the riot of Jan. 6, 2021, with the calls to “stop the steal” still reverberating under the Capitol Rotunda, 139 Republican members of the House of Representatives voted to oppose the valid electoral votes sent from Arizona and Pennsylvania, in effect endorsing the rallying cry of the insurrection.

Seventy-two Republicans voted the other way, supporting the counting of the electoral votes. What are the important characteristics that distinguish those who objected from those who did not? Some are predictable. Members may have felt more pressure to object if they came from districts and states that voted more heavily for Donald Trump. Members with fewer years in Congress objected at a higher rate, perhaps with a greater need than more veteran colleagues to make a name for themselves.

A new analysis finds another unexpected characteristic many objectors have in common, one that points to a structural danger in our election system. Objectors were more likely to have entered Congress without majority support in their initial primary. This insight arises from an Election Reformers Network database tracking members’ paths to Congress, and in particular how they fared in the primary election the year they entered Congress, before the power of incumbency kicked in.

Primaries for congressional elections have grown much more intense in recent decades. With party control over candidate nominations diminishing, races for open seats often feature a half-dozen or more candidates, and primary challenges to incumbents have become commonplace. This context increases the likelihood of “plurality winners” — candidates who win with less than the majority of votes cast — and “low plurality winners,” defined in this analysis as candidates winning with less than 40 percent vote share.

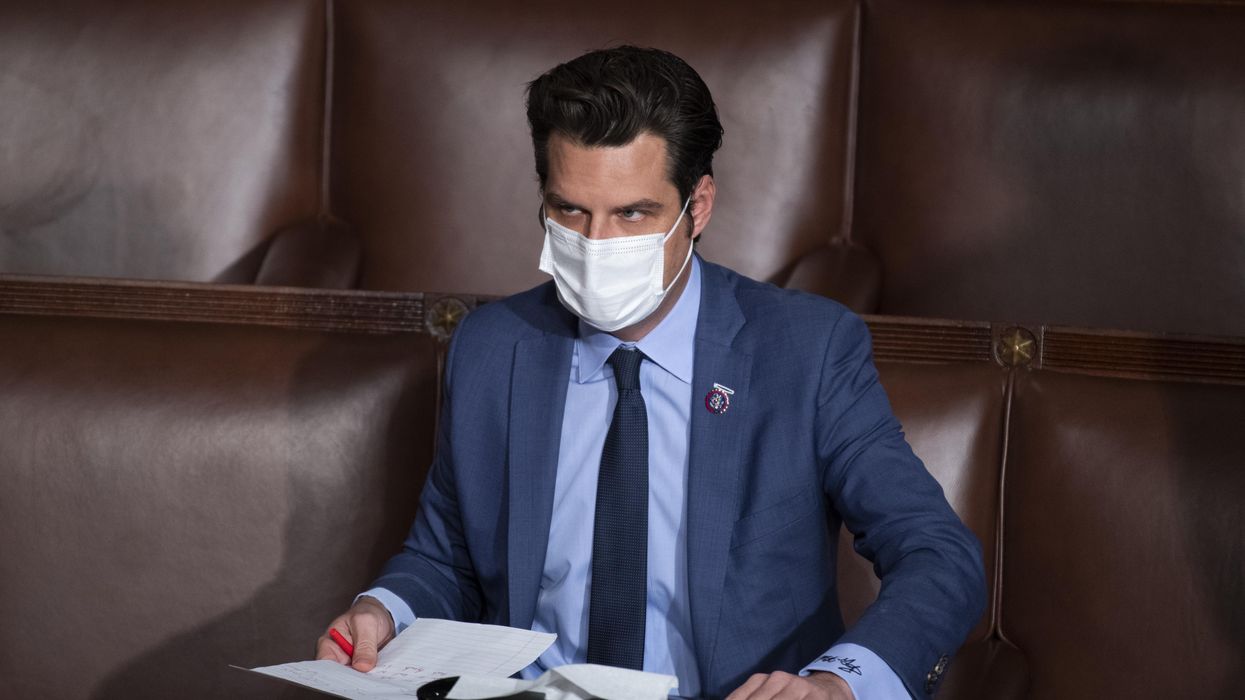

As the table below illustrates, voting to object was much more common among low plurality winners than among majority winners. More than 75 percent of the 45 members who first reached Congress via a primary win of 40 percent or less voted to object to the electoral votes of Pennsylvania and Arizona. The corresponding figure for “majority-backed” members is just over 50 percent.

The same pattern appears in the voting records of House members overall, not just on Jan. 6. A political science metric called the Nominate Score allows for comparison of members’ ideological intensity based on how they vote. Low plurality members score about a third more ideologically intense on this metric than majority-backed members, controlling for the partisan position of members’ districts.

This pattern becomes more worrisome when we take into consideration the new congressional districts emerging from the ongoing redistricting process across the states. This cycle of map-drawing has resulted in a big decrease in the number of districts competitive between Republicans and Democrats. When all the maps are finalized, membership will essentially be decided by who wins the primary in as much as 94 percent of House districts. Making matters worse, 80 percent of voters don’t participate in primary elections.

The solution to this problem is ranked-choice voting. A candidate with a strong following among one faction of the electorate but little support among other voters is much less likely to win under RCV than under conventional rules. In a crowded primary, a candidate with a plurality of first-choice votes will also need second- and third-choice votes, and (in nearly all cases) will need to reach support by the majority to win.

States can choose to implement ranked-choice voting in conventional party primaries or take a more comprehensive step and follow Alaska’s model for elections. The “top four” model recently approved by Alaskan voters opens up the primaries and allows the participation of political independents, a growing faction of U.S. voters tired of the two-party system. The most popular four candidates (regardless of party) move on to the general, where voters can rank by preference, incentivizing candidates to run positive campaigns and angle for second- or third-place votes from supporters of their opponents.

Both parties should see it as in their best interests to stem the centrifugal force making Congress a home of extremists.The constant threat of more radical primary challengers from the parties’ wings is creating deep internal divisions and stalinesque purity standards. A highly polarized Congress can’t reflect the views of most Americans, and can't manage the basic legislative functions the country depends upon.

Though the sort of extremism that led Republican House members to oppose legitimate electoral results has many sources, it's clear that our antiquated primary systems greatly worsen the problem. It’s time we put in place a voting system that will make it difficult for broadly unpopular hyper-partisans to find a path to our Congress.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift