On Dec. 14, the Electoral College will cast its votes. Barring any unforeseen outrage, a majority will vote for Joe Biden, the popular vote winner in the general election, to sighs of relief. Many may conclude the creaky Electoral College works most of the time, and that any fixes are just too hard to worry about.

That would be a mistake.

With a shift only .07 percent of the vote, we would have a second-place winner again, just as in 2000 and 2016.

And even when the Electoral College doesn't produce a second-place winner its structure deeply distorts U.S. democracy. It is the reason swing states dominate campaigns. It marginalizes voters in all other states, and it deters strong independent candidates from running. Moreover, minority rule enabled by the Electoral College is now embedded in Republican strategy. It's in their campaigns for president and governing in the White House — judging by President Trump's treatment of California, New York and other blue states.

The biggest problem with the Electoral College is not the issue most people talk about, that small-state voters have more weight. Many countries convey greater voting impact to less populated regions. In the United Kingdom, for example, the smallest parliamentary district has one-fifth the voting population — and thus five times the impact on who becomes prime minister — as the largest. Moreover, Republicans do not dominate small states: the 16 smallest divided evenly between the parties in 2016 and 2020.

The more serious problem with the Electoral College is that it compels states to allocate electoral votes on a winner-take-all basis, giving swing states their dominant role and enabling the culture of minority rule now metastasized in the Republican Party.

Winner-take-all is not in the Constitution and was not part of the founders' intent. But it is very difficult to change without collective action among states. One idea, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, would bypass a constitutional amendment through an agreement for states to give all electoral votes to the national popular vote winner. National Popular Vote survived a referendum in Colorado with 52 percent of the vote. That close result doesn't bode well for the compact's chances in the Republican-controlled legislatures that still need to approve it. The Colorado referendum also highlighted a vulnerability: The plan can require states to give all their electoral votes to a candidate who did not win that state.

What's the alternative to National Popular Vote? Nebraska- or Maine-style allocation of electors by district won't work. That approach injects gerrymandering into presidential elections and would not have stopped a second-place Trump win in 2016.

The best alternative is a constitutional amendment offering something for both sides. Republicans want to keep the small-state advantage and the state-based, rather than national, calculation of results. Democrats want results that reflect the popular vote. Both priorities can be achieved by the Top-Two Proportional Amendment, which makes states allocate their electoral votes proportionally to the top two vote-getters in the state and replaces human electors with electoral votes expressed in decimal form.

Here are four reasons this is a good idea:

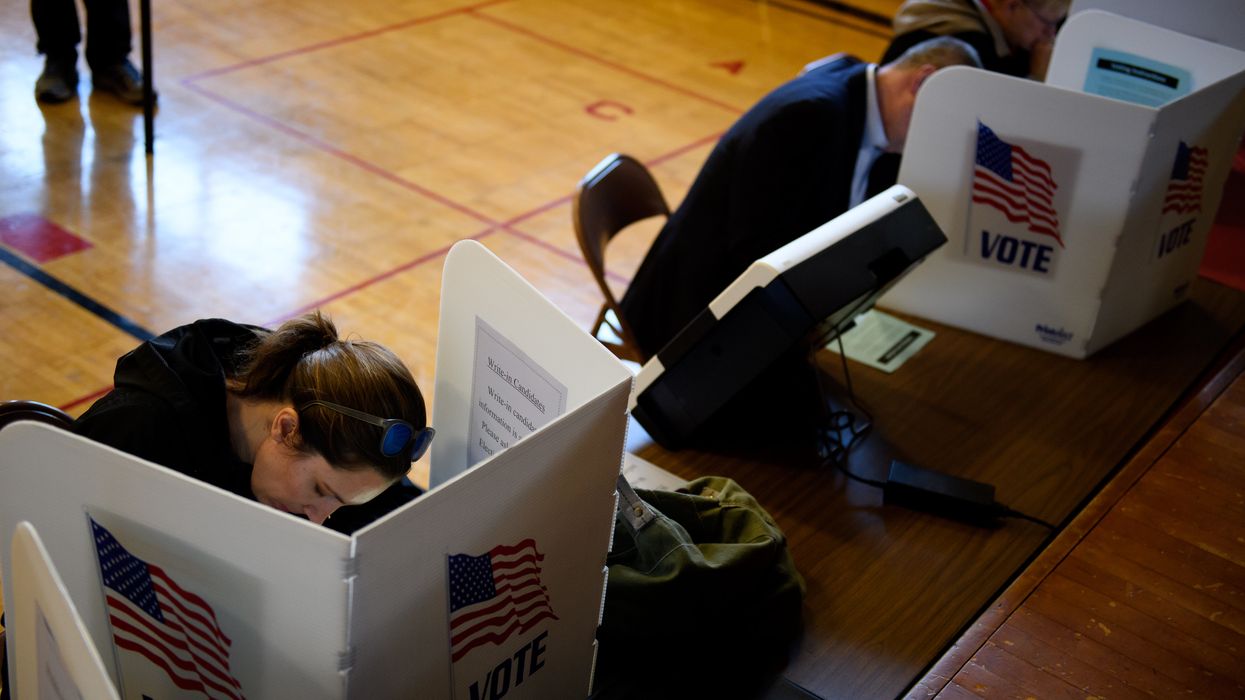

- The president would nearly always be the popular vote winner.

- With shares of electoral votes available in every state, candidates will have incentive to campaign nationwide.

- The "spoiler" problem would largely be fixed. (The 1 percent in Michigan four years ago for Jill Stein probably swung 16 electoral votes; with top-two, her impact would have been .05 of an electoral vote.)

- State results would finally reflect our true preferences, replacing the image of warring red and blue with different shades of purple.

It may sound borderline crazy to talk about something requiring broad-based national agreement when one side won't even accept the Nov. 3 election results. But the idea could appeal to Republican officials outside of swing states because it would bring the presidential campaign back to their states to help with down-ballot races.

More importantly, the democracy-distorting impact of the Electoral College is increasing, and it is not just an every-four-year problem. Allowing this institution to continue in its current form is not an option.

Kevin Johnson is founder and executive director of Election Reformers Network. Read more from The Fulcrum's Election Dissection blog or see our full list of contributors.