The nation has a new president-elect, Joe Biden. At the same time, there is no official president-elect, because the electoral process itself hasn't yet reached that point.

How can both these assertions be true? And if they are, how are Americans supposed to understand that? Most importantly, how can Americans of opposite parties get on the same page, so that we can move forward together as one country, as our new president-elect in his impressive victory speech is urging us to do?

When it comes to ending elections, there are actually two different processes at work, and they operate on different timelines.

The more familiar process is cultural. It's the pageantry of democracy, developed over decades of traditional rituals, which usually occur on election night. First, there come the projections of a winner, from the networks and other media outlets once a candidate has apparently achieved popular vote victories in enough states for an Electoral College majority.

Soon after those media projections are made, the losing candidate acknowledges the reality of the numbers and gives a public concession speech. The winning candidate, in turn, gives a victory speech and, as a practical matter, is president-elect.

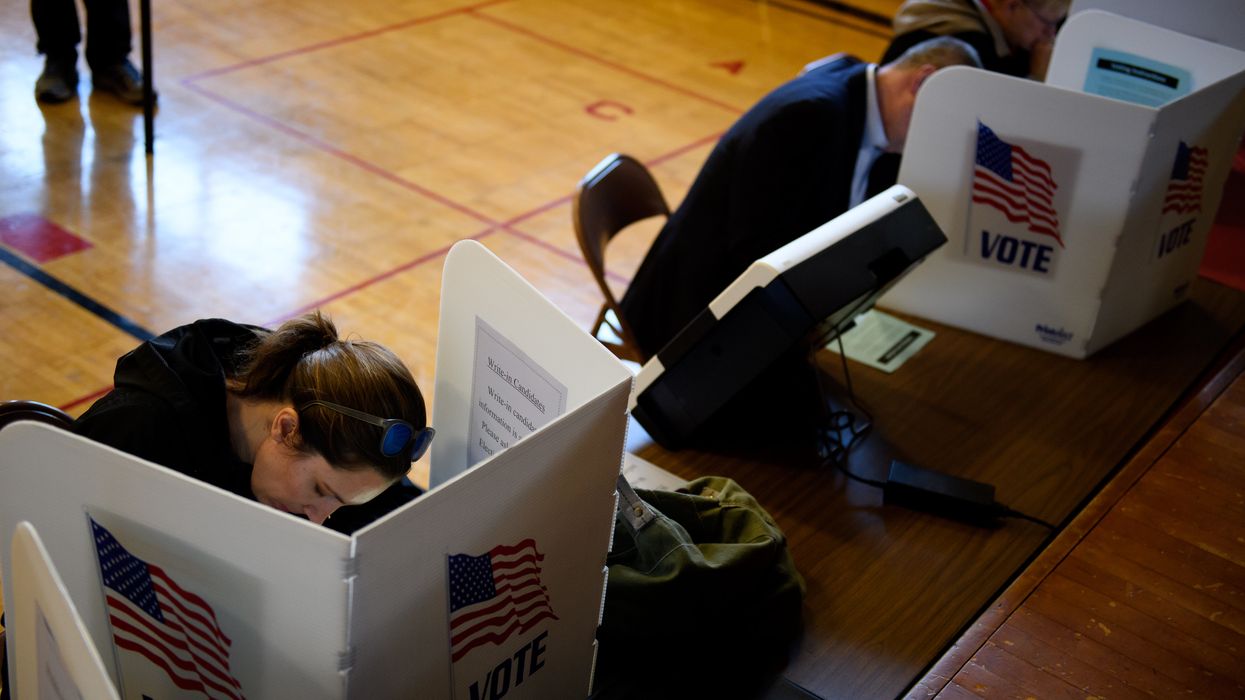

All of that, however, is far ahead of the official process for bringing the election to a close. Election night tallies need to be converted into officially certified outcomes. This requires the canvassing of returns, when the preliminary tallies are verified and provisional ballots are included in the totals, along with military and overseas ballots and any others that cannot be counted immediately.

Recounts may be necessary. This doesn't necessarily mean there were problems. It can be just an extra step of verifying accuracy. The various verification measures, so salutary for the election's integrity, inevitably take days or even weeks. It depends on the laws of different states, and how much verification is needed in any particular election.

Until the final certification of the popular vote occurs in enough states for an Electoral College majority, there is not yet a president-elect in any official sense. Technically, under the Constitution, there can't be an official president-elect until the Electoral College actually casts its votes for president. That will happen this year on Monday, Dec. 14.

As Americans, we never want to wait that long to say we have a president-elect. It was hard enough this year to wait just four days for the media's unofficial projections of a winner.

This wait has been blamed mostly on Pennsylvania's failure to change its laws to permit early "pre-canvassing" of mailed ballots, in the way that Florida and other states allow. Pre-canvassing would have been good, but it would not have permitted an election night winner, even unofficially. Enough provisional ballots needed to be counted for the media to "call" the state, and provisional ballots by definition cannot be pre-canvassed.

In 2008, Missouri could not be "called" for two weeks because of provisional ballots, although most Americans ignored this fact because Missouri that year did not matter to reaching an Electoral College majority. This year, Arizona still hasn't been called by some outlets (and perhaps was called prematurely by others), even though it made the change to early pre-canvassing of mailed ballots advocated for Pennsylvania.

As difficult as it is, Americans need to get used to the fact that sometimes presidential elections will be "too close to call" for several days or even longer.

And what is the significance of these unofficial media "calls"?

Networks and newspapers immediately labeled Joe Biden "president-elect" as soon as they made their projections Saturday. That is their First Amendment right, although it has no governmental status. But it was the basis on which Biden gave his victory speech. — a victory that Trump defiantly will not acknowledge. Other elected Republicans are struggling with what to say.

GOP Senators, like Roy Blunt, are not wrong when they observe that there is still a legal process to play out. But they should do more to recognize, as Blunt himself signaled, that this legal process will end with the same conclusion as the media's unofficial projections.

Former President George W. Bush struck the right note when he congratulated Joe Biden as "president elect" while simultaneously acknowledging Trump's "right to request recounts and pursue legal challenges."

The problem is Trump's assertion of this right, based on all known facts. It is honorable to challenge an opponent's victory when there's a good-faith basis for doing so, but it is dishonorable when there's not.

Everyone knows that Trump will never be able to admit that Biden won fair-and-square. Because of this, it is essential that other Republicans do so.

While they can wait for the certification of results to say that Biden's victory is official, they cannot wait to repudiate efforts to discredit that victory.

The message now must be Bush's: the legal process, once complete, will confirm an outcome already "clear" and "fundamentally fair."

Edward B. Foley is professor of law and director of the election law program at The Ohio State University's Moritz College of Law. Read more from The Fulcrum's Election Dissection blog. A version of this essay ran previously on the Election Law Blog.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift