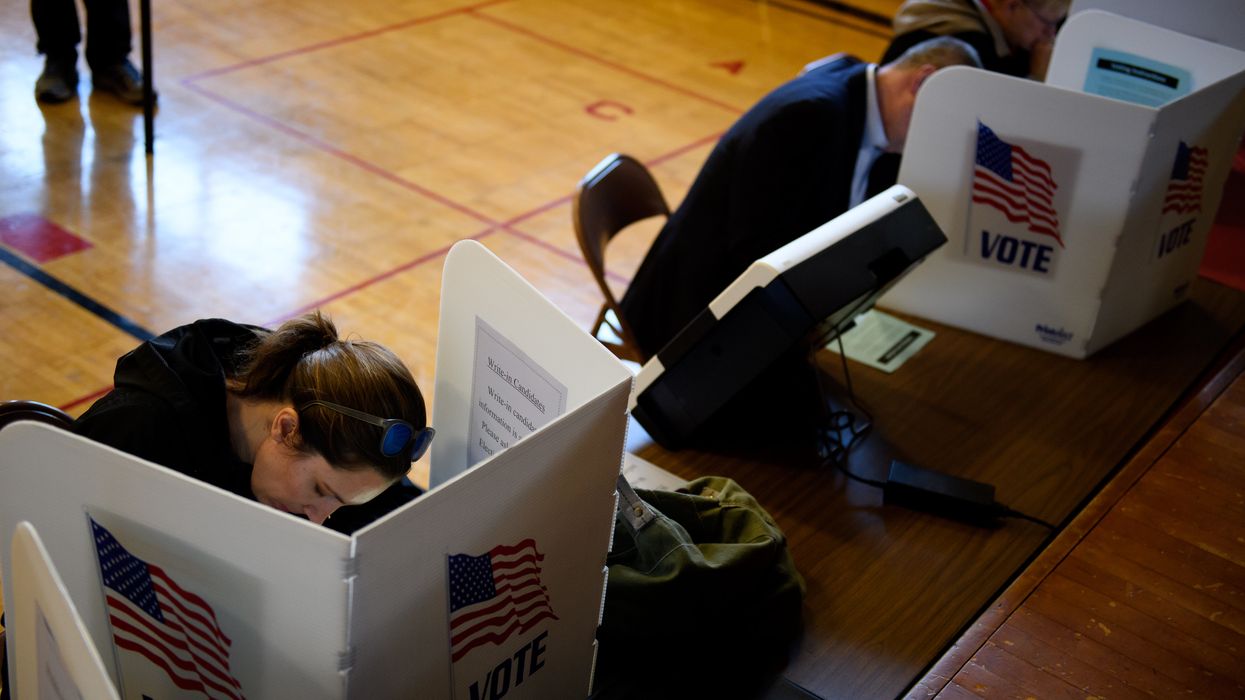

With only a handful of days until Election Day, some voting procedure questions are finally being resolved. The Pennsylvania Legislature declined to allow election officials to process absentee ballots before Nov. 3. The Michigan Legislature grudgingly allowed earlier ballot processing, in some counties. In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott's decision to reduce the number of ballot drop boxes is still in court.

These issues are all part of a great battle over election procedures during the pandemic. Most states expanded early voting and mail-in ballots this year, and those changes have been the center of a mind boggling 377 lawsuits, according to the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project.

We're not the only country holding elections during Covid-19. But a look at what has happened elsewhere presents a dramatic contrast with the United States, where public-health decisions became a partisan legal conflict.

Queensland, Australia, will hold a state parliament election on Oct. 30, with the Electoral Commission of Queensland in charge. The ECQ is an independent statutory body, and it used its authority to roll out expanded early voting and a longer application period for postal ballots. The commission also expanded a new vote-by-phone system for people who can't make it to the polls. None of these changes needed approval by the Queensland Parliament, and none were challenged in court.

In New Brunswick, Canada, the September state parliament elections saw a 100-fold increase in mail-in voting. Procedures were set by Kim Poffenroth, the chief electoral officer and supervisor of political financing. Poffenroth is a career civil servant nominated by a commission representing academic, judicial and legislative backgrounds. By law, the chief electoral officer must be nonpartisan and may not vote.

The New Brunswick vote wasn't flawless. Registration errors led to college students being disenfranchised. There's an identity-based divide between the province's French and English speaking populations, with the potential for much partisan animosity. Nevertheless, there wasn't a single court challenge to the new election procedures.

Back on April 15, South Korea became the second country to conduct national elections during the pandemic, and turnout was the highest since 1992. Massive changes to election procedures were required, including the implementation of a new vote-by-mail system. Extensive safety precautions included temperature checks of all voters. Testing and contract tracing confirmed that no Covid-19 transmissions occurred.

These adaptations weren't ordered by the country's parliament or the federal government. They came from South Korea's National Election Commission, an independent body established in the country's constitution. The commission has full authority over administrative decisions. There was one lawsuit.

These examples illustrate how much the United States is an outlier when it comes to election administration. Our system puts people with close ties to political parties in the driver's seat, determining not just broad policy but also the details of election administration. State legislatures (which express the view of the majority party) are deciding when election officials can open their mail, and governors (who often lead their state party) are deciding things like the distribution of drop boxes.

Debates about elections administration here tend to be dominated by accusations against the individual parties, rather than a recognition that a system that lets parties micromanage elections will always have problems. Recently, Republicans have been more often accused of limiting voter access. But Democrats were guilty of the same sins throughout the Jim Crow era.

If we want a path to national sanity after all this is over, it's time to start thinking seriously about putting nonpartisan election administrators in charge.

Kevin Johnson is founder and executive director of Election Reformers Network. Read more from The Fulcrum's Election Dissection blog or see our full list of contributors.