Eighteen days from when the voting stops, no battleground state has its election procedures more up in the air than Pennsylvania.

Whether to permit an extension for the arrival of absentee ballots will be decided any day by the U.S. Supreme Court, protecting or disenfranchising tens of thousands of voters.

Whether to reject ballots for sloppy signatures will be decided any day by the state Supreme Court, determining the validity of thousands more votes.

Whether to allow processing of mailed ballots before Election Day will be decided any day at the state capital, either speeding or delaying results that could settle who wins the presidency.

And then there are the continued disputes over how expansively to permit ballot drop boxes, what to do with mistakenly duplicated vote-by-mail applications, how to recover from ballot printing mistakes, how much more to regulate poll workers — and whether discarded vote envelopes sent by Pennsylvanians in the armed forces overseas are a sign of sweeping election fraud. (The big hint here: There were nine of them, not the "thousands of ballots" President Trump falsely claimed Thursday night.)

All the indecision suggests that another round of fresh legal fights is likely to be unleashed after Nov. 3 if the national contest between Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden remains too close to call — and Pennsylvania's 20 electoral votes remain up for grabs. (State law says that's supposed to be settled with the certification of election results by Nov. 23.)

"I happen to think that Pennsylvania could be ground zero in the country for determining the outcome of the presidential election because of the delays from litigation," Philadelphia election lawyer Matt Haverstick t old Spotlight PA. "I have a feeling we are going to be the Florida of 2020."

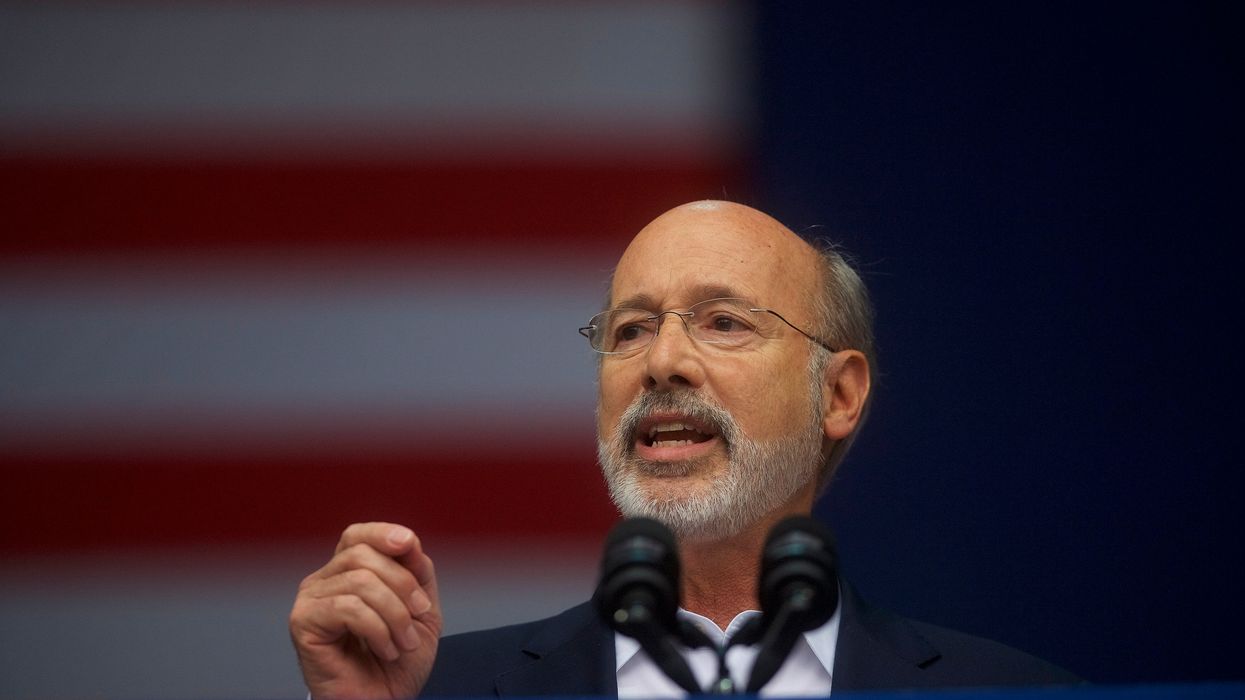

The most dramatic possible scenario involves competing slates of electors vying for the eye of Congress — one group backing Trump that gets forwarded by the Republican-majority General Assembly, and a group for Biden endorsed by Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf.

But that hypothetical would come true more than two months from now, and several more tangible disputes must be settled in the next two weeks.

In the meantime, a record 2.6 million Pennsylvanians have already asked for and received mail-in ballots, and 518,000 had been returned by the middle of the week. Four years ago, Trump carried the state by just 45,000 votes out of 6 million cast.

Assuming turnout is higher this year, as widely expected, the most important pending case looks to be the one before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Republicans are asking the justices to reverse a ruling by the state's high court last month, ordering a three-day extension for the arrival of absentee ballots mailed by the time the polls close Nov. 3. The state's justices also ruled 4-3 that envelopes with a missing or unclear postmark must be accepted, so long as there's no indication they were sent in after polls closed.

More than 18,000 envelopes were tossed because they arrived after primary day in June, or about 1 percent of the total vote.

Republicans say Election Day arrival should be the rule again, not only because the state court imposed its will on a decision that should have been left to legislators but also because the justices changed the rules too close to the election. Both arguments have fared well in a series of election cases the Supreme Court has considered since the coronavirus pandemic upended normal election rhythms this spring.

The state high court said this week it would decide another big dispute before Election Day: Democratic Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar, Pennsylvania's top election official, wants the court to prevent counties from rejecting ballots based on a subjective assessment of the signatures on the envelopes by election officials, who are not trained to see how handwriting can change over time. (About 1,800 primary ballots were rejected for this reason this summer.)

The Trump campaign wants to disqualify mail-in ballots with signatures that don't appear to match what's on file. A federal judge in Pittsburgh last week threw out a lawsuit to that effect, which also sought to lift the county residency rule for partisan election monitors and an effective ban on ballot drop boxes.

While Trump's team readies a federal appeal, his GOP allies in Harrisburg are pursuing his poll watcher and drop box preferences as their main objectives in negotiations over a last-minute election bill. But on Thursday the governor's office described his latest offer as having been spurned and said the talks are at an impasse.

Wolf's main goal is a change in state law to permit county election officials a head start of at least a few days to check the signatures, open the envelopes and stack the ballots for tabulating — painstaking work that right now can only begin the morning of Election Day. (Winners of some close legislative and congressional primaries were not clear for weeks afterward as a result of that late start.)

Such a switch would speed the vote count, assuring a vast majority of ballots are tabulated on election night and reducing the ability to credibly claim the results are being manipulated. At a campaign rally in Pennsylvania this week, Trump falsely asserted that the only way he could lose the state is if Democrats cheat. (Polling for now shows Biden with a single-digit lead.)

A spurt of worry about potential fraud quickly subsided Thursday but was supplanted by a wave of voter confusion.

The state reportedly rejected 372,000 requests for mail-back ballots that seemed fishy at first blush, but the cause of that enormous number turned out to be benign. More than 90 percent were duplicates — from people who failed to remember that, back when they asked to vote absentee in the primary, they checked a box to get a general election absentee ballot as well.

Even before the pandemic, the state had decided to drop strict excuse requirements on the books for years and to encourage more use of the mail — and the new system has proved baffling or worry-inducing to many, and overwhelming to local officials.

Officials in Pittsburgh, for example, were scrambling to get more than 29,000 replacement ballots to voters who had received vote-by-mail packets asking the to cast down-ballot votes for races in a different parts of the state

Only 4 percent of votes were cast by mail statewide just two years ago, but it was more than half in the primary.