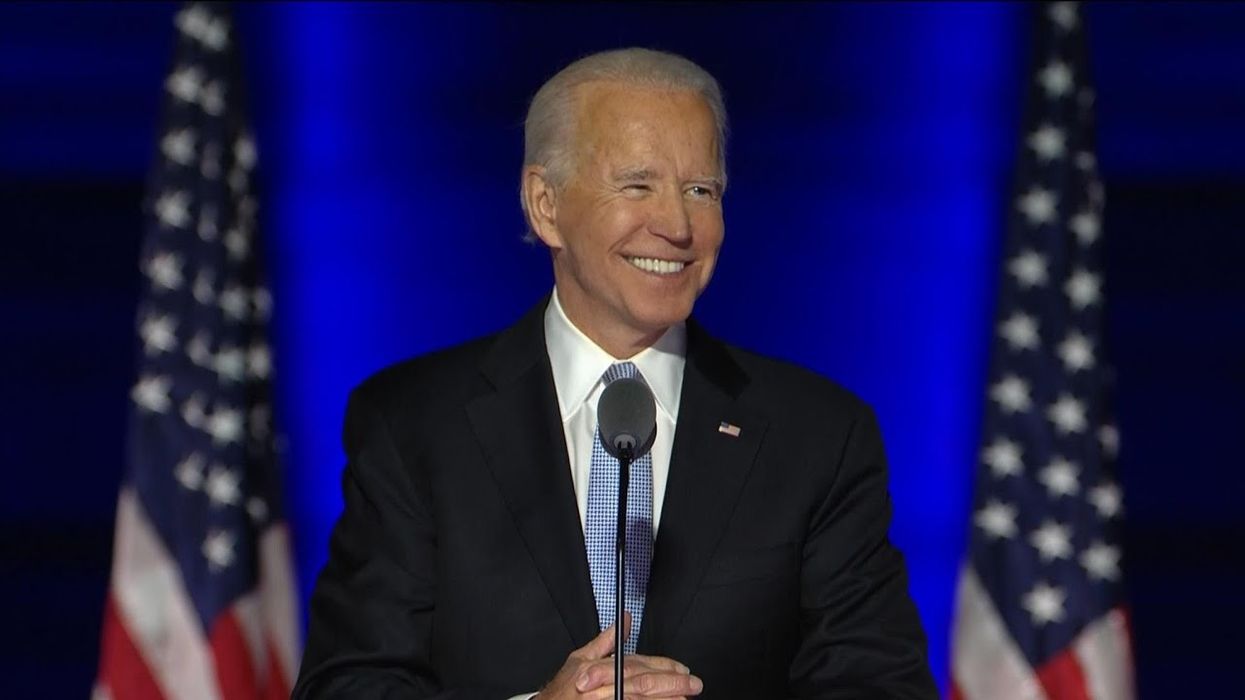

One of the most talked-about questions of this incredibly fraught election has been whether President Trump will concede if defeated by Vice President Joe Biden. Trump has fueled this concern through unsubstantiated accusations of election fraud, remarkably irresponsible statements that probably rank among the most un-presidential actions in our history. But from a legal perspective, a Trump concession would be irrelevant to the completion of the election.

We've grown accustomed to a certain sequence of events in presidential elections. News organizations project one candidate to have an insurmountable lead. The losing candidate is the first to speak, acknowledging defeat and congratulating his opponent. The winner steps before a cheering crowd, effectively bringing the election to a close.

But, in fact, election laws don't require acceptance of results or depend on the loser's concession.

Losing candidates do have the right to petition for recounts or formally contest certified results in court. And it seems likely that there will be such challenges this year. But for those actions to make a difference, the losing candidate needs real evidence, and the election needs to be close. The website FiveThirtyEight projects less than a 4 percent chance the race will be decided by a half a percentage point or less in a tipping-point state.

Once all challenges and appeals are exhausted, a losing candidate is out of options. States certify the vote, list the results for each candidate and name electors. The electors vote in state capitols on Dec. 14. Congress convenes to accept the electoral vote on Jan. 6, and the new president begins the next term at noon on Jan. 20.

Beyond the legalities, the tradition of the losing candidate congratulating the winner and accepting his or her defeat has become an important norm in our democratic culture. It would be disappointing to have an exception to that norm this year. But our norms are resilient and can withstand an outlier election.

There's a significant risk that a refusal to concede will affect civil peace in the immediate aftermath of the race. Whichever side wins, there may be protests, counter protests, and probably violence. In this context, the refusal to accept results is a dangerous and irresponsible act that could fuel violence and result in lost lives.

But as a country, we have suffered through protests and related violence before and shown our ability to heal and move on. Whatever happens, we will heal again this time.

It's important for both sides to remember we're electing a public office-holder constrained by the constitution, not an emperor. Trump's larger-than-life personality and extraordinary provocations have dominated our thinking and our news cycles for four years. That's far beyond the true role of the president. This has exacerbated the media's tendency to emphasize individuals more than the institutions they represent.

Norms and institutions may not make for compelling news, but they're the foundation of our democracy and our government. Transfer of power based on the will of the people may be the greatest American norm, one emulated by countries around the world. That norm, and the institutions that carry out the election, will function as designed regardless of whether or not the losing candidate likes it.

Kevin Johnson is founder and executive director of Election Reformers Network. Read more from The Fulcrum's Election Dissection blog or see our full list of contributors.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift