Kevin Frazier will join the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University as an Assistant Professor starting this Fall. He currently is a clerk on the Montana Supreme Court.

How much would you pay to save someone’s life? Would you pay any less if you learned that person would die tomorrow rather than today? What if the person wouldn’t die for five days? Five years? Or five decades?

As unpleasant as it may be, the above is a customary exercise every federal agency goes through when reviewing regulations. Pursuant to an executive order from the Clinton administration, agencies must select the regulation that maximizes net benefits. Agencies perform a Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA) to do just that—they tally up the forecasted benefits and costs over time and see if the latter exceeds the former.

And, though you may want to never think about BCAs again, now’s the time to do so. The Office of Management and Budget is accepting public comment on its regulatory review process, including the ins and outs of BCAs, but that comment window closes tomorrow (June 20), so we must talk about this difficult, complex topic now.

Usually BCA calculations are pretty dry. For instance, a BCA of a five-year tax on marshmallows would likely only include economic variables. The analysts would first calculate the economic benefits and costs for each year and then adjust those yearly estimates to bring them into present value. This adjustment—determining the present value of future benefits and costs—is known as discounting.

Discounting reflects the fact that $1 today is worth more than $1 tomorrow. If you had that dollar today, then you could put it in the bank and earn interest, invest in the stock market, and all other sorts of stuff that would leave you with more than a dollar tomorrow. Duh, right? The comparative value of a “today” dollar versus a “tomorrow” dollar depends on a great deal of factors—are the banks providing a high interest rate? Is the stock market crashing or thriving? Do you have urgent needs or would waiting another day be no big deal? All of those factors shape your “discount rate.” The higher the discount rate, the more weight you assign to benefits and costs in the short-term, and vice versa. A discount rate of zero would mean you assign equal weight across time.

But what if the regulation in question isn’t as fluffy as a marshmallow tax? What if you’re regulating the proper level of a known toxin in household paints: at level A, you anticipate that one death will occur in year one and nine will occur in year two; at level B, no deaths will occur in year one and ten will occur in year two.

In both cases, ten people die in the span of two years. So there’s no difference, right? Wrong…at least under a traditional BCA using a positive discount rate. Under any such a rate, the deaths that occur in year two would “cost” less. So, assuming levels A and B achieve the same total benefits, level B would have fewer total costs because all of the deaths occurred in year two. Now imagine a harder case: level A results in 100 million deaths tomorrow, but no deaths beyond that; level B results in no deaths tomorrow, but 101 million deaths in ten years.

Some people would have no problem going with level B – they might justify their decision by claiming that society can use the intervening nine years to come up with a way to save some lives or they might say that our complex, interconnected world requires assigning lives monetary value that can be integrated into a quantitative analysis.

I’ll address the second argument first – it is, to quote my grandma, “full of baloney.” I get that you can invest “today’s dollar” and earn more, but you cannot put a human life in the bank. Future lives should not be treated as investment vehicles.

The first argument is a little tougher – humans have time and again exceeded our own expectations and developed technologies beyond our wildest dreams. In some cases, it seems likely that we can innovate our way out of worst-case scenarios and save future lives. However, in many cases, regulations and their likely effects are very hard to reverse or actually irreversible. In those cases, no amount of innovation will save future Americans. In those cases, agencies should be obligated to use a discount rate of zero and equally value current and future lives.

This critical process informs the most important regulatory actions taken by the federal government. If you’d like to share your own perspective, now is the time. Visit here to find out more.

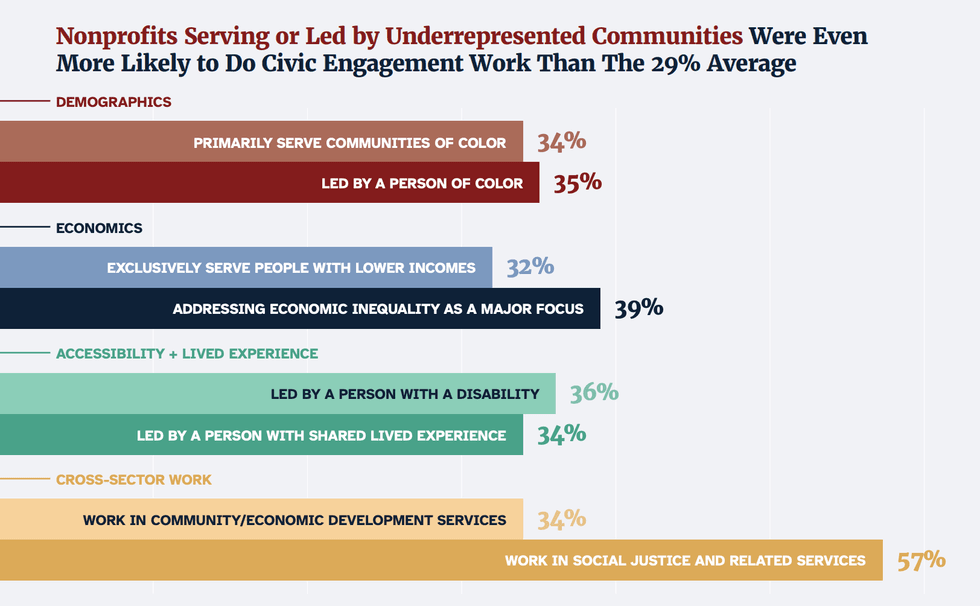

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift