Rabbi Charles E. Savenor serves as the Executive Director of Civic Spirit that provides training in civic education to faith based day schools.

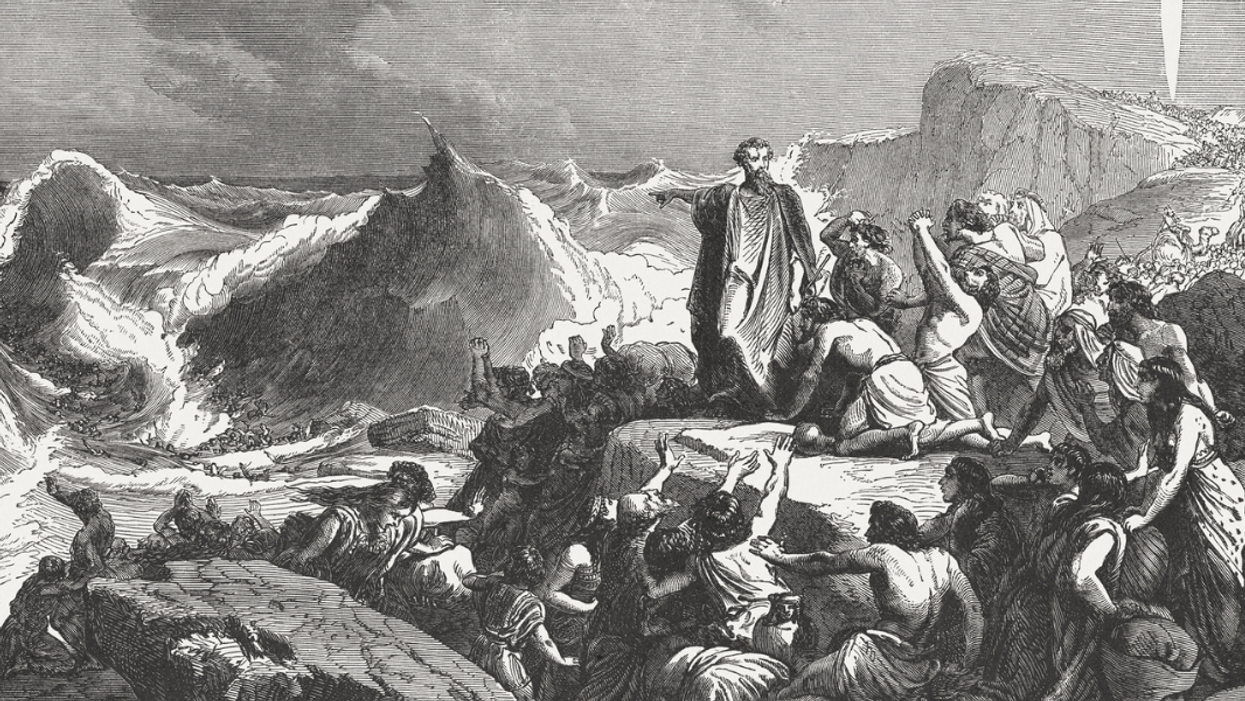

When America’s founders were imagining the great seal of this new democracy, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson suggested featuring a depiction of the Exodus from Egypt. The Israelites’ overcoming oppression of a powerful king and reaching freedom captured their imagination, as they saw themselves in this triumphant story.

While this biblical narrative inspired many revolutionaries, some of their contemporaries harbored reservations about the powerful appeal of this particular story. Slaveholders in the British West Indies and American South worried about how enslaved people would hear the Exodus story and the conclusions they would draw from it. Their fears only increased in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution in 1804. In an attempt to safeguard against another rebellion of those seeking freedom, slaveholders not only limited literacy, but also censured the Bible. So much so, in 1807 a version of the Bible was produced without mention of the Israelite Exodus.

This so-called “Slave Bible” may have removed the Exodus from its pages, but the human desire for freedom and liberty can never be erased. In fact, we know from the many African American Spirituals - like “Let My People Go” and “Go Down, Moses” - that the Exodus story framed slaves’ aspirations of reaching a “Promised Land” where freedom is a shared norm.

As the Jewish people celebrate Passover this week, the Exodus story is retold and embraced anew. What makes Passover special is not just the telling of the tale, but the internalization of its values and visions through rituals, questions, and conversation.

Our celebrations of Passover, Easter, and Ramadan are also elevated by the storytellers as much as the story. At our holiday tables, we are all educators. Many of us will be in multigenerational settings where we are receivers of our most cherished narratives that one day we will be expected to pass down to our students, children, and grandchildren. Relaying these experiences through our eyes, we become what Abraham Lincoln calls a “living history, ...a history bearing the indubitable testimonies of its own authenticity.”

It is important for us to consider that just as the Exodus has inspired hope on these shores, so too has the American experiment in democracy seeded dreams around the globe. At a time when democracy is challenged near and far, our role as a “living history” about the American story is more important than ever. Despite the United States’ challenges, divides, and conflicts, ours is a story worth sharing.

Tomorrow’s leaders need to hear not just the triumphant memories of yesteryear, but also visions of what our nation can become when a sense of common purpose prevails. When we embrace the opportunity to share how responsibility, integrity, listening, and compromise contribute to the free society in which we live today, we plant the seeds of hope.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift