Usually, the results of a presidential election provide the main drama. Usually, it is not the story of how Americans are going to vote that's packed with twists, conflicts, and a constant litany of first evers and never befores.

Of course, almost nothing about 2020 has been usual. In fact, it may be the most historically significant year leading up to a national election in memory. So the fighting over how to hold a comprehensive, safe and reliable election has often been tough to follow in the shadows of impeachment, pandemic and economic calamity.

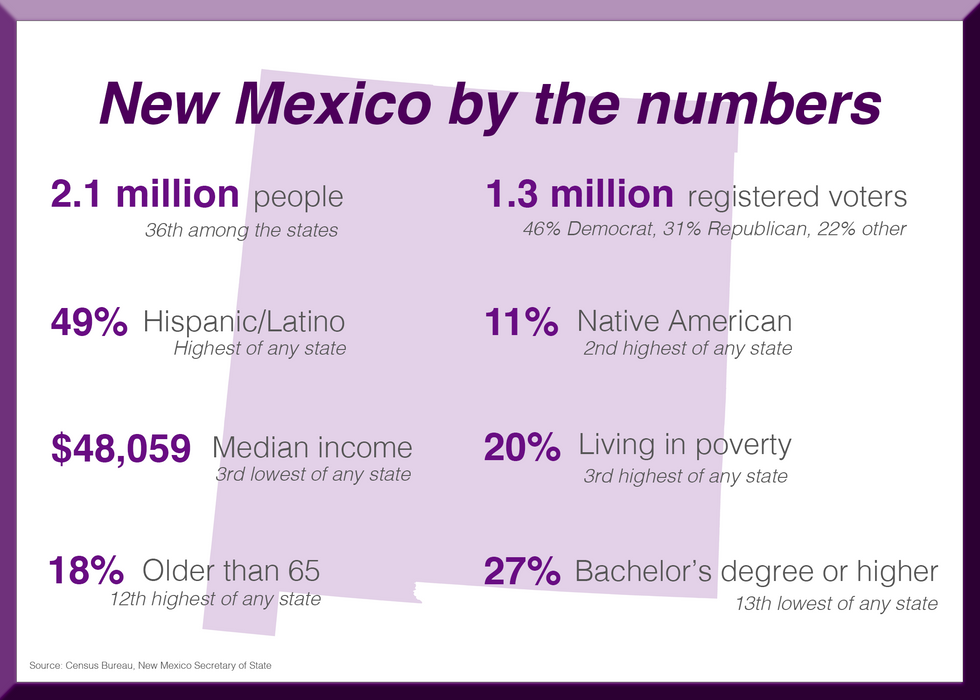

There are five weeks to go. But the path traveled so far — by good-government activists, election officials, security watchdogs, political leaders, legions of attorneys and regular citizens — becomes clear through the lens of a single state. We've chosen New Mexico. It's more rural, poor, politically blue and demographically brown than the nation. But its election experience this year nicely reflects the calamity the country's already gone through, even before the fight over the actual count begins.

Ready for the war games

As the long campaign season began, talk about a fair and trustworthy vote was almost entirely about election security.

After all, numerous investigations — by special counsel Robert Mueller, by Congress and by the intelligence community itself — had reached the same conclusion: Russia repeatedly attempted to hack into our election systems in 2016. Its efforts were mostly unsuccessful. But the mere idea of a foreign power trying to fiddle with our most sacred of democratic institutions had set off a flurry of activity to strengthen the country's defenses against election hacking.

And so just days before last Christmas about 120 local and state election officials — including New Mexico's election director, Mandy Vigil — gathered in a suburban Washington hotel ballroom for war games on different cyber-security election disaster scenarios.

Among the speakers was a former Army officer with battlefield experience. Participants worked out of binders titled "The Elections Battlestaff Playbook." Some facilitators insisted on anonymity because of the sensitivity of their security work.

The militaristic vibe was intentional, explained one of the hosts, Eric Rosenbach, an Army intelligence officer before he was chief of staff to Defense Secretary Ash Carter in the Obama administration. "Let's be honest," he said. "If democracy is under attack and you guys are the ones at the pointy end of the spear, why shouldn't we train that way?"

New Mexico entered the year better positioned than many states because it was already doing two things election security experts view as essential for assuring election integrity.

Back in 2006, it became one of the earliest states to mandate the use of paper ballots, which create a tangible record for use in recounts, to resolve disputes or to check suspicions of results being hacked.

The state also claims to be the first to adopt what's seen as the gold-standard for those checks: so-called risk-limiting audits, in which random samples of ballots are recounted until officials have statistical certainty the overall results are accurate — similar to the sampling used in public opinion polls.

A test case on voting by mail

March 10 changed everything in New Mexico, including elections.

On that Tuesday, the state Department of Health reported the first case of coronavirus in the New Mexico. Democratic Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham declared a public health emergency the next day.

Three weeks later, 27 of the state's 33 county clerks, joined by Democratic Secretary of State Maggie Toulose Oliver, went to the state's highest court seeking permission to conduct the primaries mostly by mail. It was one of the earliest such efforts after the pandemic began, but their petition presciently labeled it a public health emergency "unprecedented in modern times."

(At that time there were about 200 Covid-19 cases in the state and two deaths. Totals at the end of last week were 28,000 cases and 859 deaths.)

April 14 marked another milestone in the state's 108-year history — the first time its Supreme Court heard oral arguments on a video conference call. After deliberating two hours, the justices rejected the idea of delivering mail-in ballots to all registered Republicans and Democrats and then restricting in-person voting.

State law is clear that absentee ballots may only be sent to people who request them, the court concluded, so the most the justices could (and did) do was order applications be sent to everyone registered and eligible to vote in the primary.

It was the kind of argument, and the sort of decision, that has subsequently played out in courtroom after courtroom, as officials and voting rights groups have sought to protect voters across the country from having to risk their health in order to cast their ballots — often in the face of laws that never anticipated a year when the electorate was being told to stay away from large gatherings, such as polling places, whenever possible.

The result has been the most litigated election ever. The Healthy Election Project, a joint effort of MIT and Stanford, is tracking 300 cases — many of the most important among them yet to be decided or with the initial rulings under appeal. Many of the lawsuits are, like the trendsetting New Mexico case, focused on efforts by Democrats to ease limitations on absentee ballots. But plenty are also efforts by Republicans to make voting tougher.

State legislatures have also gotten into the act, with 49 states enacting 369 election-related laws this year, many related to voting by mail, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. That's a 43 percent increase from the roster of election-related laws enacted five years ago.

Governors have been major players as well. Seventeen of them delayed statewide or presidential primaries — and ordered second delays in Louisiana, Georgia, Connecticut and Delaware. An overlapping list of 17 decreed other changes, including ordering that all voters receive an absentee ballot or an application.

Perturbing primary problems

The primaries themselves were a mixed bag, with several raising concerns about whether safe and fair elections are possible this year given the pandemic persistence.

Contradictory and complex court rulings, in cases seeking mail-in easements and an outright delay, kept Wisconsin's April primary in limbo until the night before. Scores of poll workers, many elderly and at higher risk of viral infection, did not show. And the first big worries emerged about the Postal Service's ability to fulfill its newly vital election roll. The next big mess was in Georgia in June, when undelivered absentee ballots, a shrunken roster of polling places and brand new but balky voting machines produced hours-long lines at the polls. Later that month, a surge of mailed ballots in New York produced a several-week wait for the final result of two razor-close congressional contests.

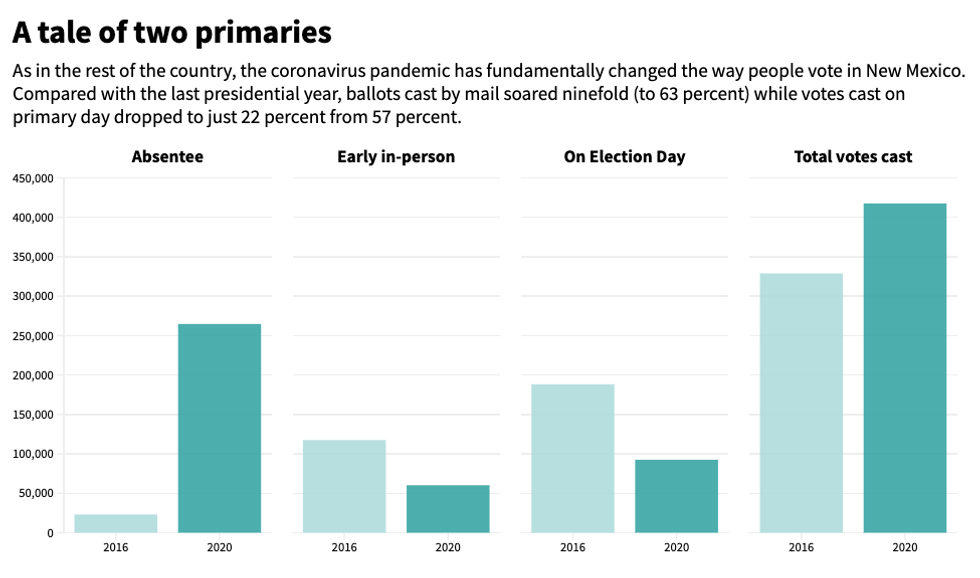

The situation was not nearly so bad, but still bad enough, when the polls closed June 2 in New Mexico. Tabulators were overwhelmed and the reason was easy to identify: the record number — 246,000 — taking advantage of the applications they'd been sent and then returning completed ballots. Overall turnout was one-quarter more than for the presidential primary in 2016 and the share of ballots cast absentee increased almost tenfold — to 63 percent from 7 percent four years ago.

Source: New Mexico Secretary of State

Source: New Mexico Secretary of State

The top election official in Albuquerque sent his staff home before midnight and told them to finish tackling the envelopes in the morning. Poll workers in Santa Fe took three days to finish their count. And in the end 2,400 ballots statewide weren't counted because they arrived after the polls closed — a rejection rate, echoing the nationwide number in primaries this year, of 1 percent.

Because primary turnout was the highest in almost three decades, even though Joe Biden had clinched the Democratic presidential nomination by that point, there looks to be another big burst in November — even though the former vice president is a near lock to carry the state's five electoral votes and color the state blue on the national map for the seventh time in eight elections. (Hillary Clinton won it last time by 8 points.)

The hottest race is in the one usually Republican congressional district, which covers the arid and sparsely populated southern half of the state. Democrat Xochitl Torres Small, who narrowly won in 2018, is in a tossup match against former GOP state legislator Yvette Herrell.

The legislators respond

Within days of the primary, the New Mexico Legislature was considering a bill to address some of the problems with the primary. The original bill by the majority Democrats would have allowed county clerks to proactively deliver ballots to everyone on their rolls in early October, ending the by-request-only rule. Republican legislators balked, echoing President Trump's persistent and baseless claim that so many ballots in circulation will guarantee election fraud.

That provision was abandoned, and instead a law enacted at the end of June permits clerks to mail applications for absentee ballots to all. Counties with two-thirds of the state's people are already planning to do that, and more are expected to join them.

The law also protects Native American voting rights by mandating that polling places on reservations may not be closed without written permission from tribal leaders.

"The Covid-19 crisis has created many challenges, but voting should not be one of them," said Democrat Linda Trujillo, a sponsor of the bill in the state House.

The fight goes postal

It's perhaps unsurprising that one of the most venerable institutions of the government, the Postal Service, is at the center of the next chapter of a saga that has swept away so much confidence in our most hallowed democratic institution, the election.

A Pew Research Center survey in March found 47 percent of Americans holding a "very favorable" view of the USPS, but an AP poll in September found just 34 percent with "great confidence" in the post office — a sharp 13-point drop in just six months. In between, Postmaster General Louis DeJoy became a household name and the face of the election integrity controversy.

Brand new on the job — without any previous postal experience, but with stock options in a Postal Service competitor and a long record of generous donations to Trump and the GOP — DeJoy launched an overhaul of the financially troubled USPS. It included moving out many in top leadership, several who had worked on election mail issues; banning overtime, including to handle election mail; and removing sorting equipment from some distribution centers.

In August, Democratic Attorney General Hector Balderas of New Mexico and the attorneys general of 22 other states filed three separate lawsuits to make DeJoy reverse those changes at least through the election. "The Postal Service is a vital lifeline for rural New Mexico, and this action threatens to disproportionately harm our Indigenous communities, from their daily living to their ability to participate in our democracy," Balderas said.

An important preliminary victory came a month later, on Sept. 17, when a federal judge in Washington state (ruling in the suit New Mexico had joined) temporarily blocked all of the operational and policy changes made by the Postal Service this summer.

"At the heart of DeJoy's and the Postal Service's actions is voter disenfranchisement," Judge Stanley Bastian wrote, concluding there's strong evidence "the recent changes are the result of an effort by the current administration to use the Postal Service as a tool in partisan politics."

At the same time the state was pressing its case against the Postal Service, however, New Mexico's elections director was expressing confidence in her working relationship with postal officials in the state.

One reason for optimism is another piece of the new elections law, which set an absentee ballot application cutoff nine days earlier than in the past. The new date is Oct. 20, a full week ahead of the post office's recommended deadline for getting completed ballots in the mail and being confident they'll arrive in time to be counted.

Like 32 other states, New Mexico law says envelopes that arrive after the polls close on Election Day must be tossed, although a series of court rulings have ordered deadline extensions in several swing states.

The latest, maybe not last, dispute

Another response to concerns about ballots delayed too long in the mail and not arriving in time has been to deploy more drop boxes. More than half the 2016 presidential votes in Colorado, Oregon and Washington — three states that conducted almost all elections remotely before the pandemic — were deposited in these secure canisters.

But like almost every other aspect of election arcana this year, this seemingly simple alternative has become embroiled in partisan controversy.

Trump has sued in federal court to block the planned use of drop boxes in battleground Pennsylvania, arguing they will invite fraud. GOP secretaries of state in reliably red Tennessee and Missouri decided against them, the former citing possible cheating and the latter saying they are against state law. Democrats have successfully sued to get more than one dropbox in each county in purplish Ohio, but the Republican in charge of the state's elections has appealed.

New Mexico is one of eight states with laws outlining how drop boxes may be used. Secretary of State Toulouse Oliver's office announced last week that several million dollars in federal election funds will be spent to install drop boxes across the state.

No one has sued to stop her — yet.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift